A test of endurance: Satyagraha at ENO

ReviewAlthough “Contemporary Opera for the ‘Britain’s Got Talent’ Generation” might be an apt way to describe Phelim McDermott’s Satyagraha, it would be unfair to both the performers and the audience to describe it as such, due to the mammoth stamina that is required by both parties during a performance of this epic Glass score.

The production felt flat and clichéd, with questionable directorial decisions that transformed the historic London Coliseum into something reminiscent of a GCSE drama classroom whose school had a surplus of newspaper and sellotape after deciding to cut their art program to save money. The movement direction came across as lazy and haphazard, with most of the production taken up with the slightly clunky chorus moving in slow motion across the stage: a directorial decision that seemed to scream “I don’t know what to do here so you should all just move slowly until this aria ends”.

Unfortunately, we have come to expect this lack of attention to aesthetics in the big opera houses, and as theatre and film move strides across the artistic plane, opera tends to fall flat on its face due to its reliance on tradition, outdated gimmicks, and its clumsy and naive understanding of mass audience appeal.

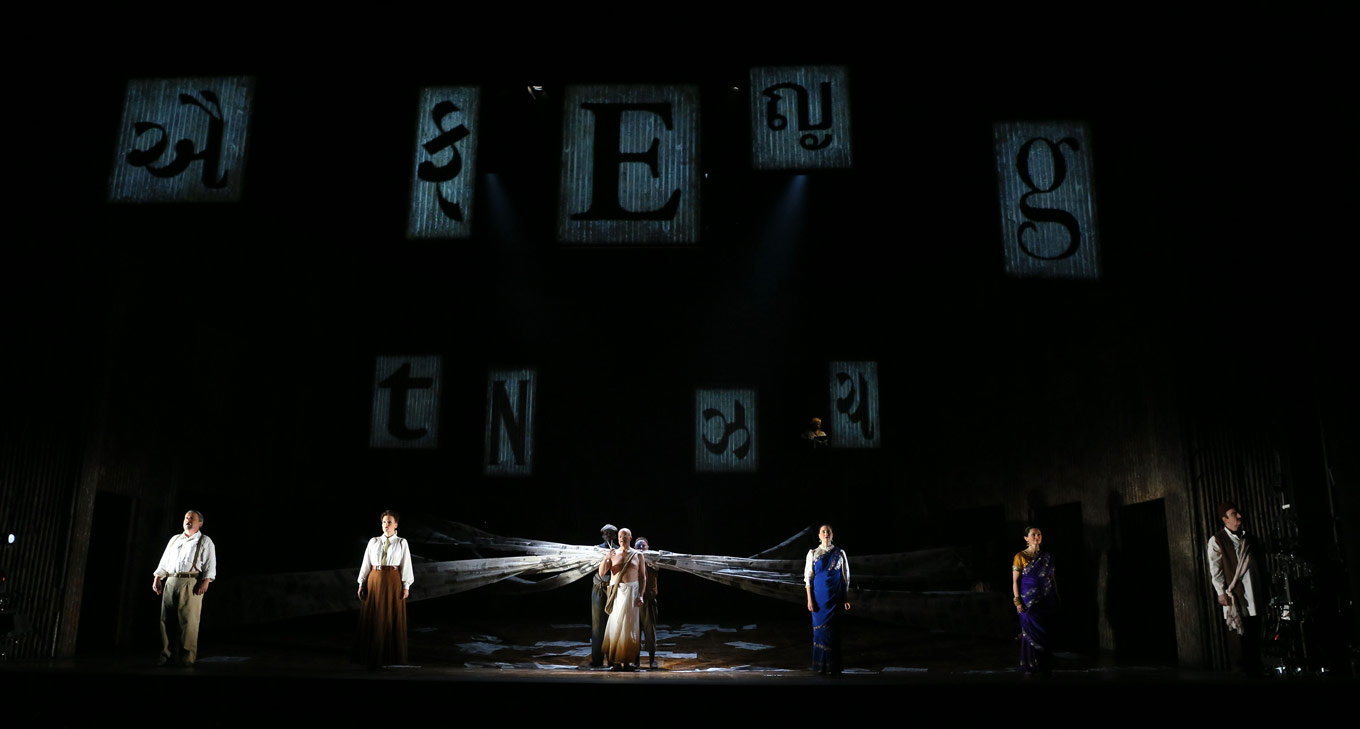

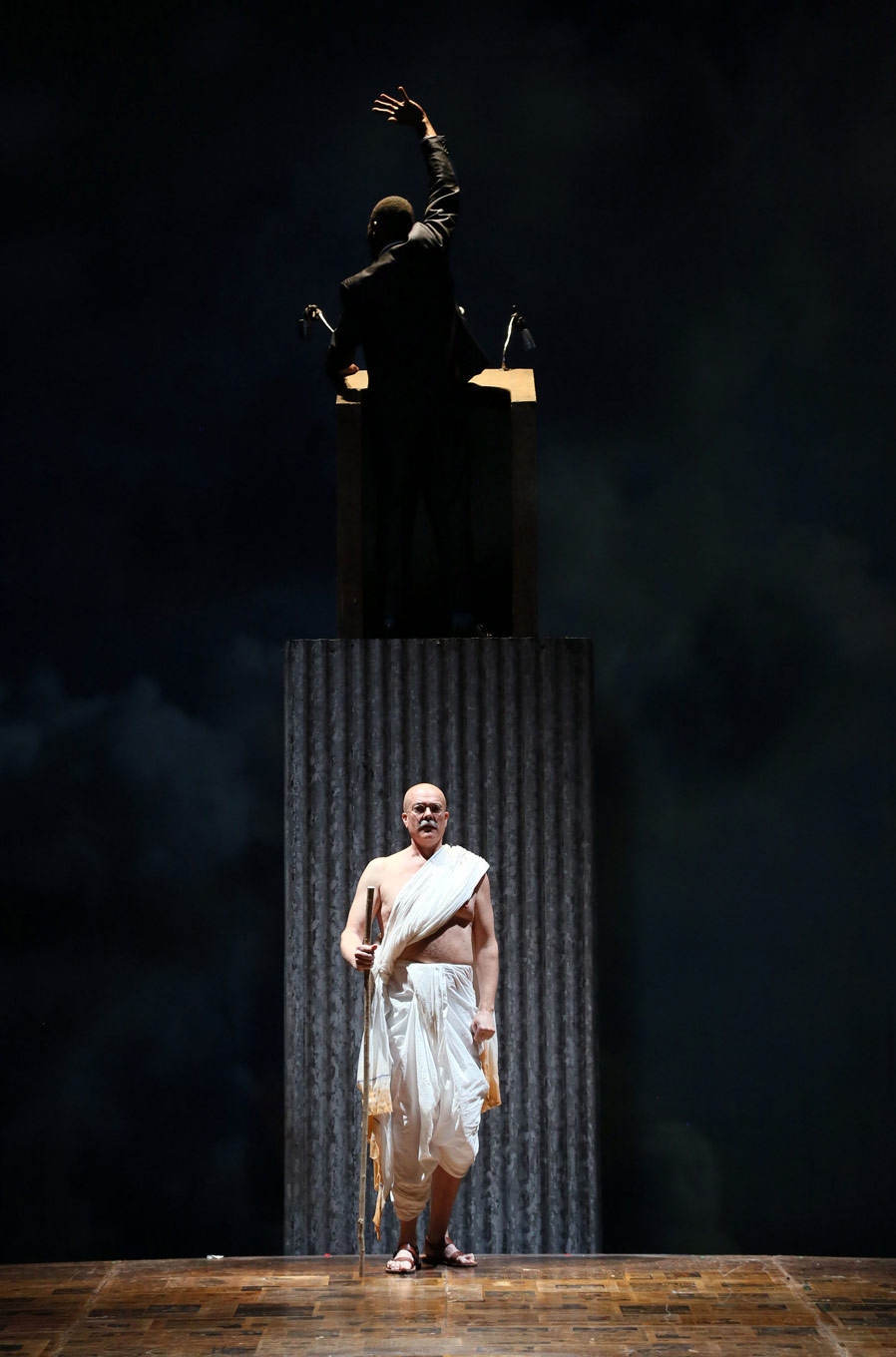

The actual design of the opera - done by Julian Crouch - was jaw-dropping at times; giant puppets strode across the stage, the lighting moved in parallel to the music, and the portrait-style vignettes of Tolstoy, Tagore, and King were absolutely stunning. Unfortunately, most of these moments were too fleeting to be described as spectacle and were quickly packed away in favour of more “slow walking”, a decision that again felt clunky against the meditative nature of the score.

Musically, the production was quite good. The orchestra were kept perfectly in time under the masterful baton of Karen Kamensek (and how incredible it is to see another female conductor in a big musical institution!) and one could tell that the singers really had an understanding of Glass’s score! It was refreshing to not see a clash of musical egos that so often appear at the big opera houses, and Toby Spence (Gandhi) in particular remained calm and in character throughout.

Most of Philip Glass’s music is a test of endurance for the performers, and I wholly congratulate the cast and orchestra for the patience with which they executed the score - but, for my two cents, the music didn’t quite “pop”. At times it felt lethargic and seriously restrained from its full potential and this, coupled with the direction of the performance, made the whole thing feel flat and tired, not something you’d expect from an opening night.

There is a worryingly rich tradition of theatre directors with little knowledge of music being invited to direct huge productions in famous opera houses, and Satyagraha really showed the flaws of this concept. The score itself is meditative and hypnotic, but it certainly isn’t standing still. The music constantly changes and reinvents itself, sifting away and sliding back in new forms. I’m not entirely convinced that the director paid as much attention to the music as he did his own grandiose vision because during the opera it becomes so clear that the music isn’t solely about repetition (a dangerous misinterpretation of the minimalist movement), it’s about evolution. Overall, the production felt like a marble interpretation of the director’s ego that refused to move with the wind.

Comments