Amici e Rivali: Two gentlemen and friendly rivalry in Verona

ReviewRossini, two terrific tenors and a first rate musical ensemble—what’s not to love? Plenty, if this bel canto extravaganza had followed the route taken by so many of those “opera aria” recordings in which we get a heady dose of familiar favorites, often lacking in spontaneity and emotional depth.

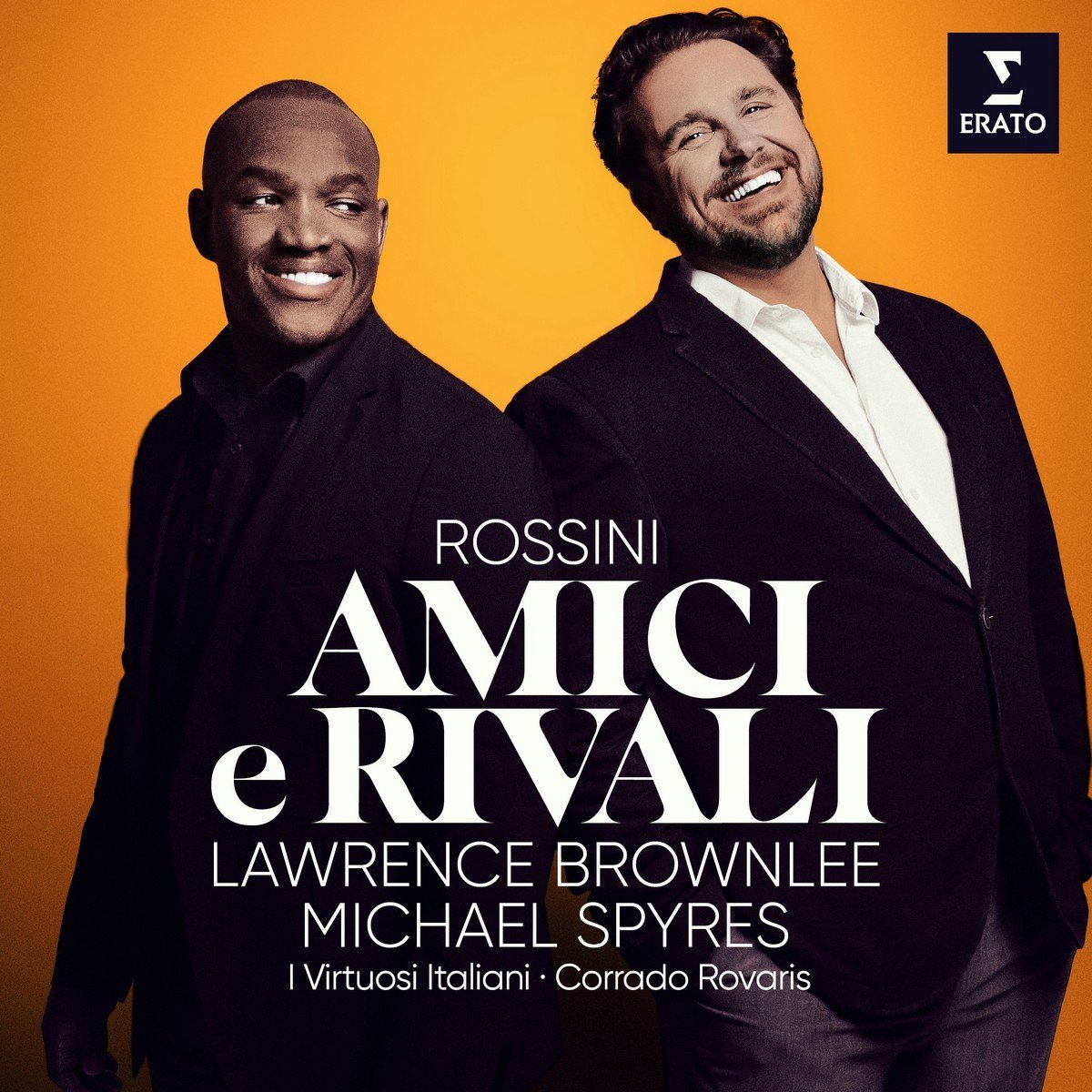

But we don’t get that in Amici e Rivali, an excellent release from Erato featuring Lawrence Brownlee and Michael Spyres. Instead we get arias, duets and trios (the tenors are joined by mezzo-soprano Tara Erraught and fellow tenor Xabier Anduaga) that are thoughtfully interpreted and artfully sequenced to mimic the construction of a Rossini opera. Its most winning feature, besides the competing tenors who are in full bloom here, is that it flows.

The singers are accompanied by the protean ensemble, I Virtuosi Italiani, lead by Corrado Rovaris, recorded on stage at the Teatro Ristori in Verona. A remarkable venue equipped with a state-of-the-art recording studio linked its the stage, Teatro Ristori bestows a bright and resonant sound on the recording. The orchestra performs with stunning élan as it plays through the heft and sparkle of Rossini’s compositions. Placed front and center, the singers are perfectly balanced with the musicians creating gorgeously delicate yet dynamic sound and a sense of immediacy.

Brownlee, replete with flourishes amidst his golden sound, holds court with Spyres who exerts authority with his majestically vibrant voice. The booklet accompanying Amici e Rivali introduces two other tenors, both from Rossini’s day, Giovanni David and Andrea Nozzari, who sang many of the roles that Brownlee and Spyres take on. Brownlee, for the record, is the light lyric tenor who associates historically with David while Spyres occupies the darker lyric tenor, or “baritenor”, as the range is sometimes known, evoking Nozzari. Since this is a rivalry, albeit a friendly one, listeners may want to decide if they prefer those stratospheric, stand-alone high notes that Brownlee launches with regularity or the integrated flourishes that Spyres so fluently provides with his commanding lower register.

Soaring high notes and vivid vocal coloring create sure-fire thrills.

In the booklet these friendly rivals expound at length on each other’s vocal styles. They sound like Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal gamely talking about how keen competition improves their game. It was common in Rossini’s day for his tenors to exchange parts despite the difference in vocal range. David and Nozzari did this with some frequency. The practice is smartly avoided on Amici e Rivali, though it could be a fascinating indulgence in concert, perhaps for an encore or two. Now there’s a rivalry.

Some listeners may prefer moderation when it comes to the tenor based pyrotechnics that ignite this recording. Soaring high notes and vivid vocal coloring create sure-fire thrills but thrills depend on relative rarity and risk being diminished by such concentrated exposure. With fireworks fairly exploding, Amici e Rivali skillfully mitigates that possibility by virtue of its adroit sequencing, leaving plenty of room for beautiful singing outside that most thrilling of bel canto bubbles.

Spyres definitively shows that his darker register can inhabit the same heights as Brownlee.

Would it be a crime against Rossini to begin such a project with anything other than the eternally effervescent Il barbiere di Siviglia? Perhaps not but the comic opera’s Act I duet, “All’idea di quel metallo” is a rousing opener that finds the deviously paired Figaro (Spyres) and Almaviva (Brownlee) engaging in snappy repartee that is quintessential Rossini. This single excerpt encapsulates the conspiring natures of the clever barber and his crafty Count and shows that their much heralded camaraderie between the two tenors is no fluke.

After such an engaging comic opening the recording takes a dramatic turn with six lesser known Rossini operas, Otello, Armida, La donna del lago, Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, Le siège de Corinthe, and Ricciardo e Zoraide, and stays there. These excerpts, being less familiar bel canto fare, offer relatively untrodden opportunities for the vocal spectacle to come. Four of the works receive multiple tracks and thanks to Rossini’s own excellent construction in tandem with their sequencing, the recording retains a sense of variety and freshness.

Ricciardo e Zoraide follows Barbiere, receiving four tracks of what may be the most engrossing moments in the opera, at least for the male singers. The bittersweet “Donala a questo core,” between Agorante, King of Nubia and Ricciardo, a paladin Knight, Spyres and Brownlee respectively, are two parts of a love triangle. Their duet unfolds with soft harmonies and a subtle show of Rossini’s genius for creating distinct characters with similar vocal lines. The orchestra is subdued as it depicts the pathos underlying the conciliatory tone of the work.

Another duet,”Deh! Scusa i trasporti,” from Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, again shows remarkable development of characters within the same melody. It is arch and fast paced in pitting the devious Duke of Norfolk (Brownlee) against the trusting Earl of Leicester (Spyres), in another royal conflict tensely reflected by taut strings and driving woodwinds.

The multiple tracks for La donna del lago and Otello both provide virtually non-stop opportunities for Brownlee and Spyres. Were it not for the duet from Elisabetta placed between these selections, their virtuosity risks running into the “thrill” factor. As it is La donna del lago deals with situations and issues that are familiar within Rossini’s oeuvre and therefore the material can feel self-conscious, especially when excerpted. This is not to diminish the skill required in execution but it does limit dramatic impact. Otello, quite a departure from Shakespeare and Verdi, assigns much of the most challenging music to Rodrigo (Brownlee), reduces the villainy of Iago (Anduaga), and tames Otello (Spyres), by casting him as well as the other two characters as tenors. Showing that bel canto can fall prey to its own rhythms, the music at times suggests domestic farce rather than abject tragedy. Still, the supporting singers in both works are afforded their moments. Erraught shows signs of being a formidable Elena and Desdomona and Anduaga, an intriguing Iago.

For this listener “Céleste Providence” provides the loveliest singing on Amici e Rivali, no contest.

Armida is an intense story driven by heroism and the whims of the sorceress Armida, disguised as the Queen of Damascus. Ubaldo (Brownlee) and Carlo (Anduaga) are dealing with the wavering commitment of fellow warrior Rinaldo (Spyres), a knight of the Crusade, who is smitten with Armida. Furious duets and trios ensue as Rinaldo is persuaded to abandon Armida and remain faithful to the cause. Spyres definitively shows that his darker register can inhabit the same heights as Brownlee and Anduaga admirably enter the competitive tenor fray in this trio.

Rossini revised his other wartime opera, Le siège de Corinthe and adapted it to a French libretto by Luigi Balocchi that elevates the work from ancient travails to universally relatable experience. “Céleste Providence,” the third track devoted to the opera, finds Brownlee at his agile best as the warrior Nécolés, with restrained and deeply emotional singing that is rich in high notes and embellishments. Spyres joins him as Cléoméne, governor of Corinthe, in haunting vocal counterpoint. Pamyra, daughter of Cléoméne and love interest of Nécolés, enters providing Erraught with a brief but aching moment in what becomes a trio of ultimate resolve. It is lilting, spiritual and inexorably sad. For this listener “Céleste Providence” provides the loveliest singing on Amici e Rivali, no contest.

Comments