An extended mad scene: Glory Denied

ReviewSpare a thought for Gaetano Donizetti (who celebrates his 220th birthday later this month), the acknowledged master of operatic mad scenes with whom all operatic composers have to reckon. Though he composed those in spades, whether or not he considered writing an opera that was in its entirety a mad scene is a secret that must remain lost to the ages.

Such an operatic phenomenon I found in Long Islander composer Tom Cipullo’s Glory Denied on November 6, 2017 at the Hobby Airport. You read that correctly: the venue for this performance was in a repurposed Air Terminal Museum, complete with exhilarating sonic effects provided by the coincidentally perfectly-timed takeoffs of diverse airplanes. Based on the eponymous oral history by Tom Philpott, Cipullo’s first opera (2007) concerns the story of the longest-held prisoner of war in United States history, then-Captain Floyd James “Jim” Thompson, who endured the privations of imprisonment and torture by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese armies for just short of nine years. Ultimately promoted to colonel by the time of his retirement in 1982, his repatriation saw his children and wife become estranged from him, and the only country and worldview he had ever known disappear.

Cipullo’s harmonic writing is astringent and uncompromising, not for escapists, with rare digressions into chordal harmony, yet his command over the nine-piece orchestra was quite commendable. I perceived the musical style to specialize in being multiple shades of one color, rather than merely monochromatic. The sole exception to this trend was a gorgeous cello solo by Barrett Sills which highlighted a montage toward the end; this transcendent piece felt far more natural and vocally oriented than many of the vocal solo numbers. Conductor Geoffrey Loff, whose work I have previously identified with delightful Parisian winds in La Traviata, did a commendable job in keeping the work flowing naturally (in spite of itself) and the ensemble balanced.

In that light, the most essential insight I can give into actually understanding this work is that the structure is necessarily unprecedented. To say “experimental” is misleading, because there were formal sections, but these sections were arrayed in a purposefully disorienting manner, as befits the subject matter. Essentially, I perceived the two acts of this opera as being, in reality, two separate operas (the first about Thompson’s captivity, the second about his traumatic return) that could not be more different from each other. Further, its staging inclines me to perceive this piece to be a dramatic cantata with perfunctory staging and operatic music. (In particular, the incessant choreographed blocking during quotations of official letters, which were set in a busy and unnatural manner, struck me as rather ritualistic and fussy.)

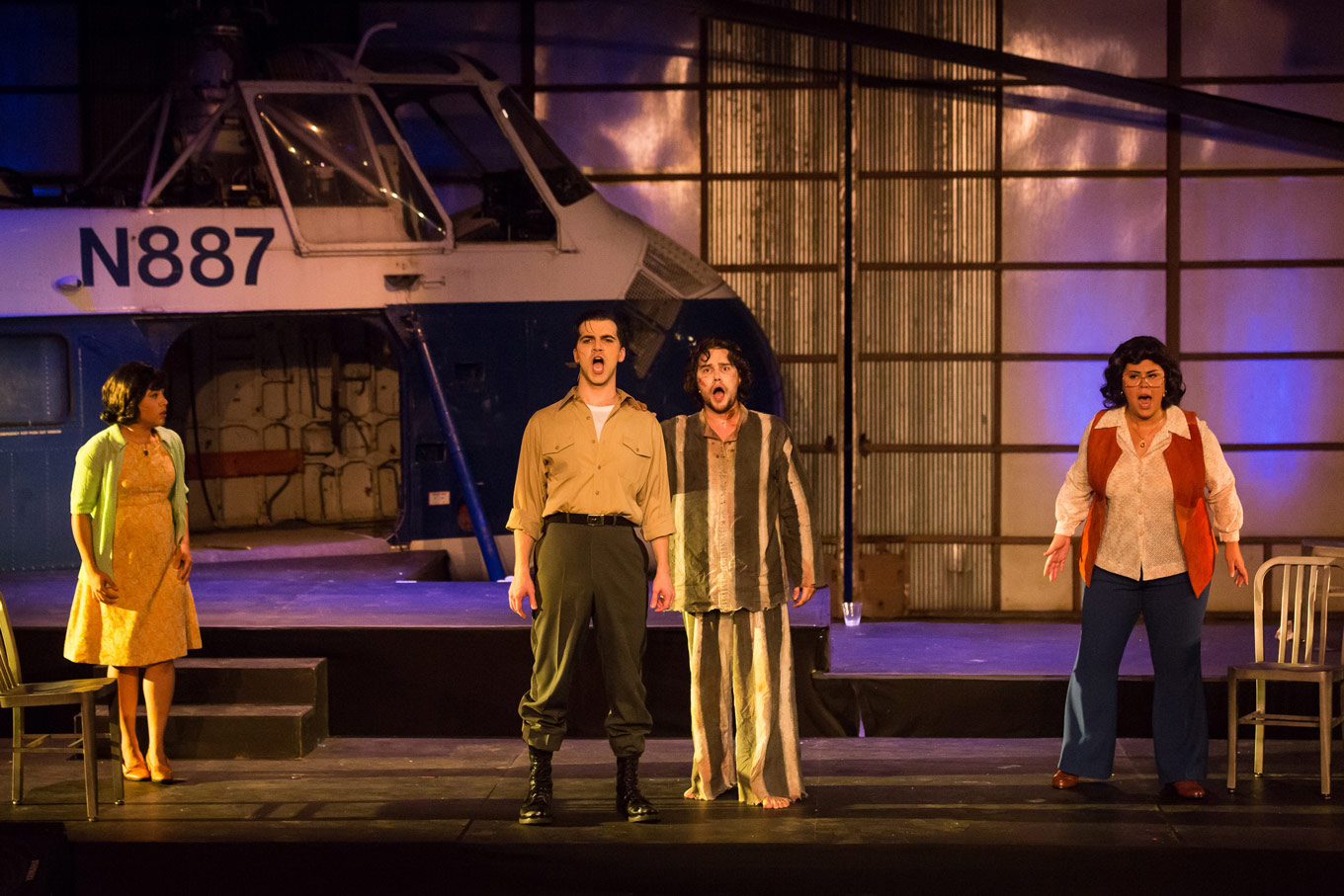

The cast consists of two personae split up among 4 singers: the closest equivalent of which I know for such a casting is Igor Stravinsky’s Renard. Thompson is played by tenor Mark Thomas (Younger) and baritone Ben Edquist (Older); his wife Alyce (decidedly not a Penelope) is played by soprano Alexandra Smither (Younger) and soprano Karriann Otaño (Older). Together, these characters sing all at once most of the time to piece together a mosaic-like retelling of the protagonist’s life. Whereas the orchestra is not often split up into different ensembles, Cipullo achieves a great deal of timbral variety in his vocal writing. In particular, the Younger and Older variants frequently exchange lines in a single composite narrative of their characters. Smither (a tireless advocate of contemporary music who will be performing with Ars Lyrica Houston this Sunday) sported a Jacqueline Bouvier wig which highlighted her, and her era’s, crushed optimism; she well depicted a state of perpetual insanity and wishful thinking for the entirety of the first act, with numerous exuberant, scintillating, stratospheric passages, where Otaño well played the jaded exponent of the rising feminist movement, being well inclined vocally towards her numerous dramatic moments.

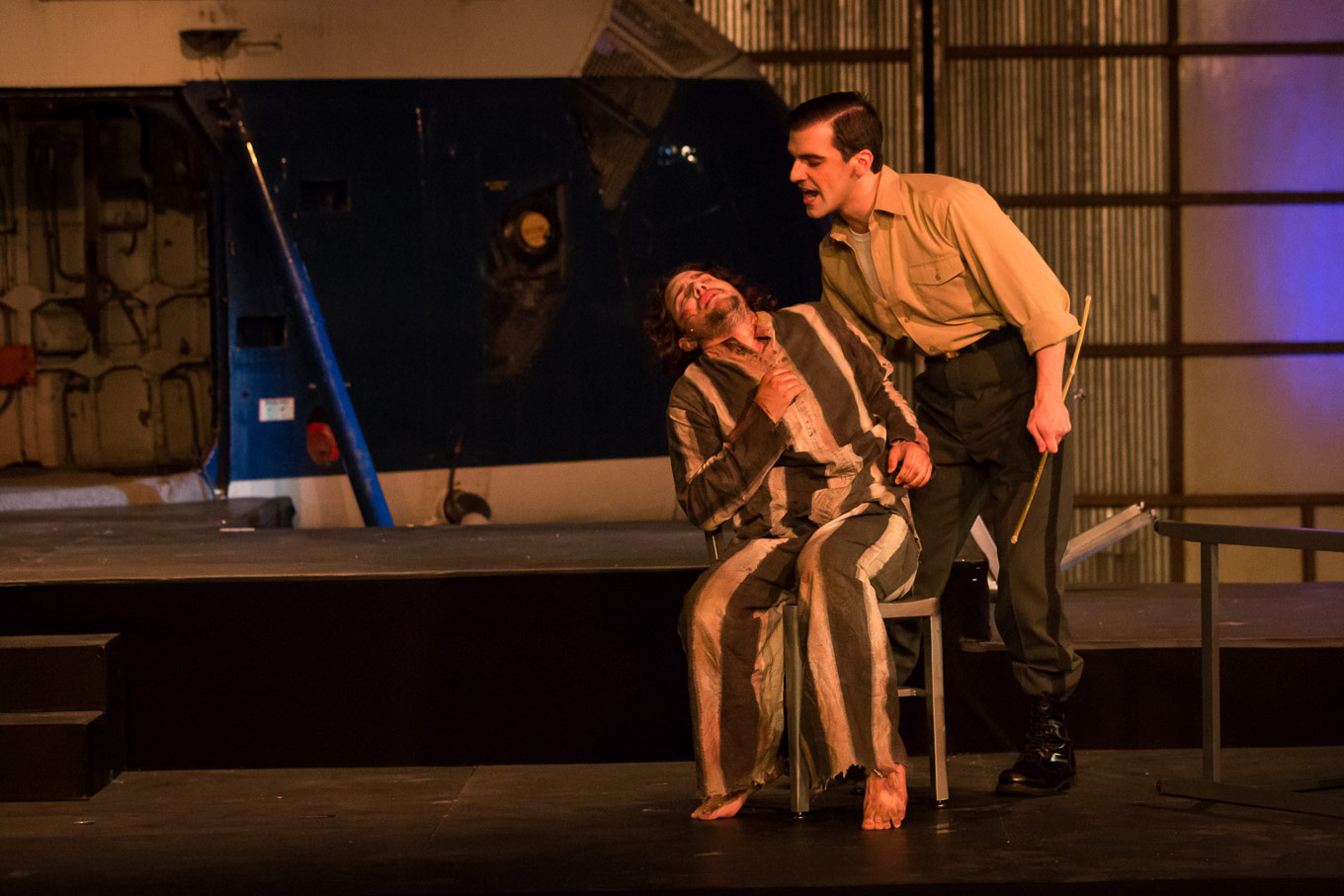

As mentioned before, I perceive Glory Denied as an extended mad scene. In addition, all of these characters have some sort of mad scene in the course of the work. A particularly effective example was Younger Thompson’s maniacally intense, yet touchingly devout, recitation of Psalm 23, complete with interjections from the rest of the cast; indeed, Older Alyce had particularly strong, cynical remarks that struck me as referring to the “thoughts and prayers” that many a congressperson might invoke upon responding to some mass catastrophe. Older Thompson played a very interesting double role, revisiting the role of his tormentors upon his hapless Younger self with sadism worthy of Baron Vitellio Scarpia, while simultaneously serving as one of the tellers of his own story; indeed Edquist’s facial expressions were quite terrifying.

The first act is written in a through-composed manner, and was by far the superior half. It was crafted in such an intense way that left me wondering how anything could possibly follow it, with a well-crafted, claustrophobic atmosphere. However, the orchestration felt consistently “busy,” a quality that generally I find distracting, even though the ample space in the venue prevented the score from being perceived as “noisy.” There was less portrayal of the characters’ existential isolation than I might have expected, but rather an emphasis on their torment all at once. I found this to also lead to a lack of dramatic suspense, which is one reason I hesitate to call this piece an opera. In other words, I found it less powerful than aggressive.

The second act, on the other hand, was made up of all the work’s arias. I have no idea why they were even there, honestly; these set-pieces came as a complete curveball, particularly after the first half, as saccharine digressions into tamer musical language, just to show that the composer is capable of writing artificially tonal arias for inclusion in the next American Aria Anthology. They merely confirm that Francis Poulenc is still my go-to model for writing tonal music in an unaffected, natural manner. All of them ended in a trite manner that made them feel divorced from the rest of the act, for the sake of obligatory applause moments. After each of these arias, I kept on asking, “Is this the end of the opera?” as each felt so uncompromisingly final, none leading naturally to the next, and since this was a dramatic cantata, there was certainly nothing preventing it from being so interpreted.

I did enjoy Edquist’s first mad scene, a patter recitation of all the changes in American society and morality that disorient him. His final mad scene, where he shows how Capt. Thompson is suppressing his previous traumas, is deliberately left with a feeling of hanging in mid-air; I definitely appreciate the reference to the finale of Wozzeck here, but it did not feel nearly so cathartic as that masterwork. Either act would stand better alone, in my humble opinion, and the combination of the two into one opera made the whole feel to me unwieldy at best.

This work does succeed in its desire, as the composer explained in a talkback, to give an idea of the angst of the time period for the current generation, and it does successfully highlight the plight of disregard for veterans’ care that casts a pall over the legacy of our great nation. However, Cipullo’s stated desire to write about “real people” must be taken with a grain of salt. Rather, I perceive the shades of real people somehow coalescing to form an experience that could never possibly approximate Capt. Thompson’s harrowing experience, which is not to say that this piece is so ambitious. If, in expecting to hear about real people, you do not expect Puccinian verismo or any sort of dramatic immediacy that might render them “realistic,” then you will be a lot more open to receiving a world of American music which will probably define this country’s legacy for years.

Comments