An isolated tenor in an operatic masterwork: Les contes d'Hoffmann

ReviewIn its current incarnation at the Metropolitan Opera, Bartlett Sher’s 2009 production of Les contes d’Hoffmann renews hope for a tired institution. Composer Jacques Offenbach wanted to write a dramatic opera to eclipse the operettas that made him famous. As a young man, he encountered Les contes d’Hoffmann, a play written by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré that dramatized three E.T.A. Hoffmann stories. He thought it could be good operatic source material. Years later, Offenbach approached Barbier to write the libretto and the two began collaborating on the opera. With his health in decline, Offenbach desperately tried to finish the work, but died before he could complete the orchestration and witness the premiere.

A shame, because Hoffmann is an operatic masterwork. Offenbach seamlessly shifts between styles and techniques. He employs ear-worming tunes one moment and sweeping melodies bursting with gravitas the next. His dramatic writing measures up to his comedic writing. Combined with a mastery of irony, character building, story telling, and orchestration, Offenbach wrote an under-appreciated gem.

That said, this production’s prologue opened with a sequence of generic opera tropes that undermined the opera’s quality. One cliché followed another: a bad silent-movie love-pantomime, uninspired park and bark narration, a silly “Oliver Twist” money pouch, muggy chorus acting, and way too many people standing on tables. This brand of stale opera is what convinces people the form is dying.

The first clue that the evening would improve was the appearance of mercurial bass-baritone Laurent Naouri who played the Four Villains. Naouri wisely eschewed overt villainous qualities, shading his characters with tenderness and humor. As Lindorf, he related to Hoffmann (Vittorio Grigolo) like a concerned father who wished his artist son would give up writing and get a real job. Naouri projected well in the hall and his timbre suited the villains. Like Jeremy Irons as Scar in The Lion King, Naouri’s voice was warm, enveloped, and invitingly sinister.

The opera’s protagonist, a fictional E.T.A. Hoffmann, tells three stories of heartbreak. In this production, the first story triumphed. It opens on a laboratory/factory. A Dr. Evil-looking physicist named Spalanzani (Mark Schowalter) prepares to unveil his newest creation: his “daughter”, the android Olympia (Erin Morley). At Spalanzani’s lab, androgynous, head-shaved misfits lounge with life-sized manikins resembling blow-up sex dolls. Unusual carnival people wander about. The circus folk are lovingly portrayed, never judged for their non-normative proclivities. Hoffmann was the outsider here, too naïve and boring for this unique world.

Hoffmann purchases rose tinted glasses from the villain Coppélius. Seen through the magic glasses, the world looks like an idealized version of itself. Hoffmann puts them on and immediately falls in love with Olympia.

Spalanzani’s laboratory molts into a twinkling outdoor carnival ground filled with spectators. Suddenly, the spectators fwump open identical white umbrellas, each with a large eye on its canopy. Arranged in a bulging quarter-dome spanning the stage, the umbrellas spin mesmerizingly, building to the big reveal: Olympia.

Erin Morley singing Olympia’s famous doll aria “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” was an example of MET opera at its best. Morley knocked off the first stanza, rippling through the coloratura effortlessly. Olympia may be a machine, but Morley is not. Her voice was tenderly human, without any bracing or metallic quality. Her singing was precise yet musical, never mechanical.

Olympia powers down in the middle of her presentation. The servant Cochenille (Christophe Mortagne) rushes in and winds her up; then things got crazy. Morley’s ornamented coloratura was so delicious in variety and astounding in execution that the crowd whooped and gasped (this writer politely double-fist pumped in his chair). The MET audience buzzed as miraculous gymnastic feats gently tumbled from the soprano’s throat.

And the comedy: Morley’s Olympia scrolled from modest to coquettish to aggressive to sweet. Impossible to control, she made an ass of her chauvinist creator. Combining dramatic ingenuity and unmatched vocal prowess, Morley enlivened the MET audience who showered her with continuous applause.

Over two hours remained. Though a vocal pinnacle was reached, the evening continued to evolve. The fair grounds clear. Olympia, shut down, is stored in a cavernous, dark space. Hoffmann follows, hoping to claim her. Behind Hoffmann and Olympia are two identically dressed couples dancing languidly. Upstage center, a prototype manikin of Olympia observes the trio of couples. The eerie duplications emphasize that Olympia is a man-made commodity, and that Hoffmann is one of many depraved suckers who, in place of a genuine human relationship, wants blind affirmation and a vessel to express himself on. He reflects the age of free internet porn, when young men can avoid the vulnerability of relationships by relying on computers for sexual gratification.

Hoffmann’s act two lover, Antonia (Anita Hartig) is an innocent but extraordinary artist. Unfortunately, her worried, domineering father, played by the formidably voiced bass Robert Pomakov, forbids her from singing. He does so for two reasons: first she has a weak heart that threatens to give out from over exertion. Singing will kill her. Second, her voice has the same timbre as her dead mother. Her singing fills her father with unbearable grief.

But forget all that for a minute because it was the servant Frantz who stole the act. All four of the servants, played superbly by Christophe Montagne, charmingly bumble about, but none as endearingly as Frantz. Picked on for his deafness and deemed incapable, Frantz nonetheless maintains a vibrant spirit, buoyed by his love of performance.

Frantz is forbidden to sing by Antonia’s father. His voice is irritates the old man. But left alone on stage, he radiates charm and confidently claims that with proper instruction, he could be a great singer and dancer. He even has an instruction manual to guide him. His thinned voice wails sweetly through exercises and he squeals as he hikes his leg up on the back of a chair. He is a perfect amateur, impossible to discourage, delighting in his private art.

Frantz is called back to work. He folds and rips and folds and rips his singing and dancing instructions. Oh well. But then, with tattered papers in hand, poof! A squeeze of his palms, and voilà! The papers are whole again. A delightful trick and poignant metaphor for Frantz’s resilient spirit.

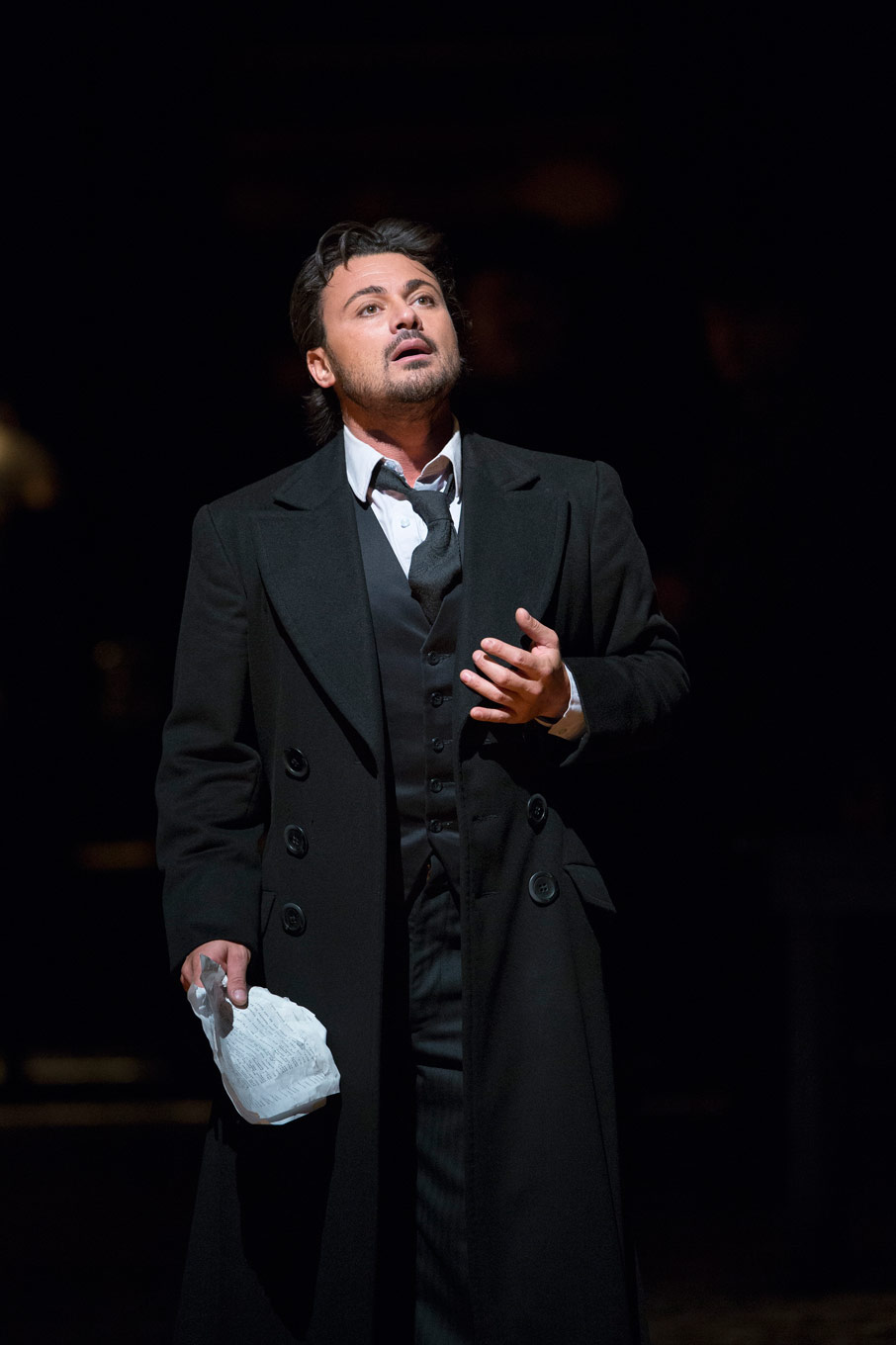

The love duet that followed dropped the energy Mortagne’s ebullience had built. Grigolo’s Hoffmann resembles his Rodolfo or Romeo; nothing distinguishes the character from the other romantic tenors in his repertoire. Throughout the opera, Mr. Grigolo was a dramatic island, set apart from his fellow players. He seemed primarily interested in his own singing, which is undeniably impressive. His relationship to other characters was general, like he had met them all before, but could neither recall their names nor the circumstances under which they met. He faked his way through interactions with stock gestures and operatic clichés that fit the “tenor love interest” mold. Maybe dramatic sacrifices are necessary to maintain one of the most consistent tenor voices on opera’s biggest stages.

Later in the act, a whimsical, silhouetted horse-drawn carriage flowed on stage, so cleanly backlit that it appeared two-dimensional. The audience gasped as the villain Dr. Miracle opened the coach door and stepped out. No one imagined a carriage so other worldly could hold a living person. In this act, the villain is benevolent, like Death in Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden”, duty-bound to bring Antonia to her grave. Antonia’s death song, delivered thrillingly by Ms. Hartig, is a triumphant choice of love over life. She literally sings herself to death, unwilling to restrain herself from musical expression.

Finally, the action moves to Venice. The set opens into a spacious, twinkling outdoor garden/bordello with piles of barely dressed women. Unfortunately, the production slid back into the typical MET trappings: unengaged park and bark, stock opera gestures, and bland relationships. Mortagne and Naouri were the exceptions. As Dapertutto, Naouri went full-villain after an evening of careful dramatic restraint, at last slimy and sinister.

The third act climaxes in a sextet with chorus that ranks among the greatest large ensemble numbers in the repertoire. Characters from the previous acts filled the stage, worlds colliding for three minutes of musical ecstasy. No gesticulating needed (someone tell Schlémil) for this well-justified stand and deliver.

The evening concluded – an undisputed success. The crowds scuttled to their cabs and 1-trains a little lighter, buoyed by the spirit of a master composer still awaiting his proper due.

Les contes d’Hoffmann continues at The Metropolitan Opera through October 28. For details and ticket information, follow our box office links below.

Comments