Aria Guides: "Aprite un po' quegli occhi"

How-ToFigaro’s final aria in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro is one that separates the men from the boys. It’s endlessly interesting for dramaturgs, since Figaro breaks the so-called “fourth wall” and addresses the audience directly for the first time the show. He’s fed up with women and their shenanigans, and it’s one of rare times we really see him lose his cool. Musically, it’s all about stamina.

If you’re learning this aria, you’ll want to include your voice teacher in the process. In addition, I offer up some tips through experience, about how to get a head start on making this mountain of an aria as easy as it can be.

Follow along in the excerpts below, or get the whole picture starting on page 193 of this score

The recit

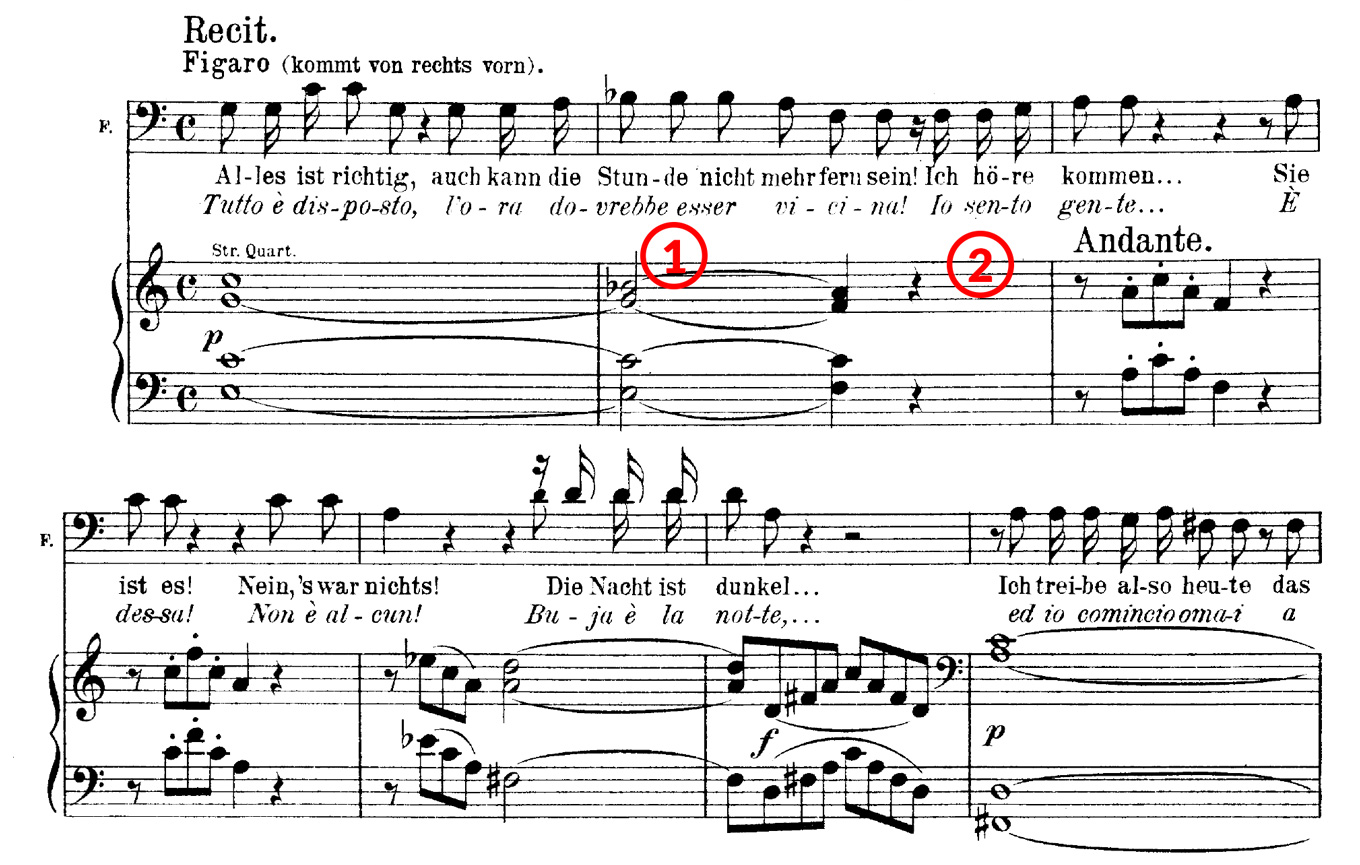

- Something about the way this text is set makes it easy to land on the wrong emphasis of the word “esser” (the stress should fall on the first syllable). That second B-flat technically gets both [ɛ] vowels, so take a bit of time to really hear yourself finish the word “dovrebbe” and begin the work “esser”.

- At “Io sento gente…” a new idea starts. I think it’s fair to mark a caesura right after you finish “vicina”, and start “Io sento” at a new pace. The staccato orchestra interjections should be reactions to you, so really lead the sentiment of the new phrase.

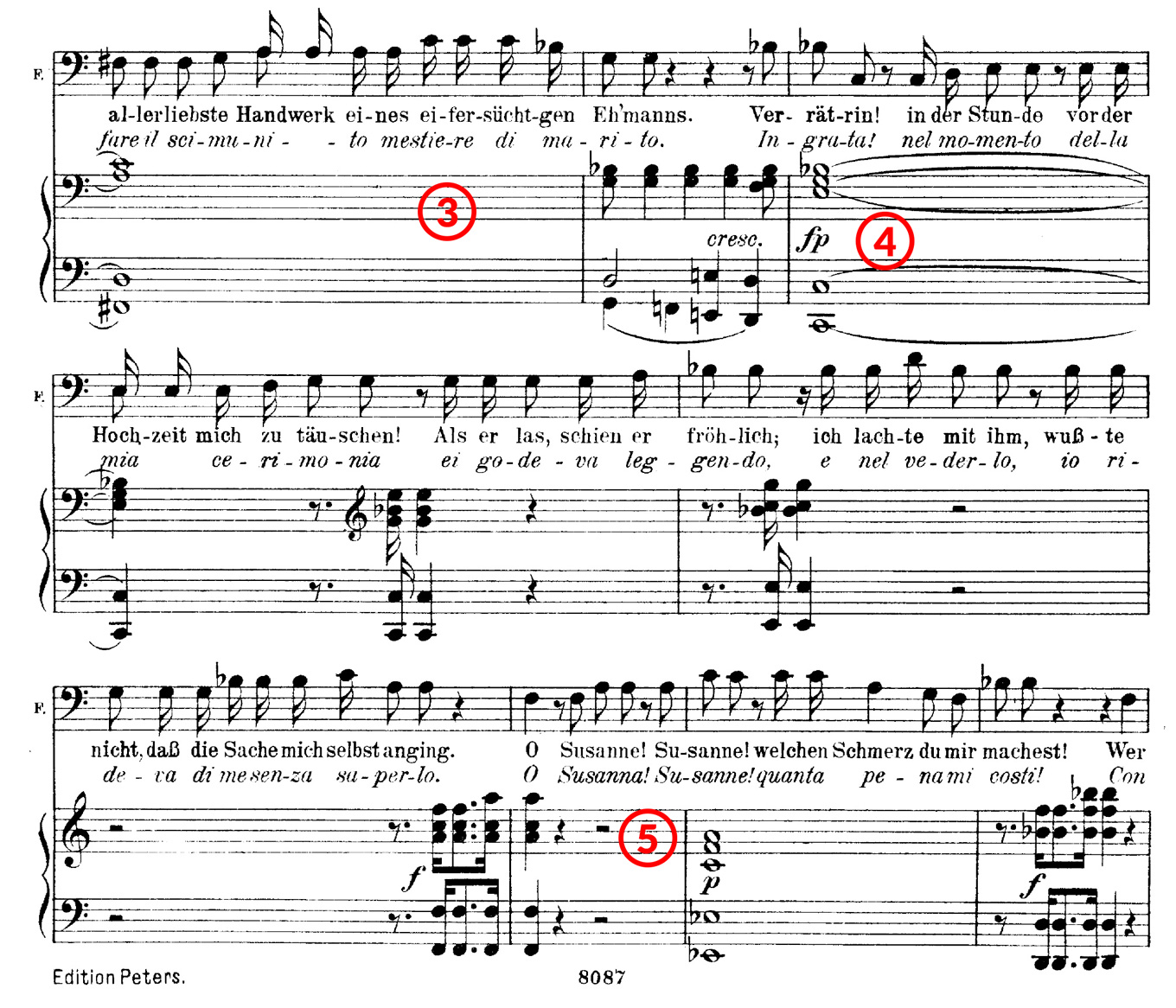

- When you do this aria with a conductor or a pianist, he or she needs to know when you’ll be arriving at the downbeat, under “marito”. There’s no real need to rush through all the “fare scimunito…”, which will make it easier to follow your text; it’s basically about being consistent, and not throwing any rhythmic surprises in the last beat of this measure (“mestiere di ma…”).

- Keep in mind that this section, starting at “nel momento…” is one giant sentence that doesn’t end until two lines later, at “senza saperlo.” The orchestra chords that punctuate the words “ceremonia” and “leggendo” shouldn’t slow down your momentum; rather than fitting around their events, let them join your ongoing phrase.

- When you repeat Susanna’s name, the chord marked at a piano dynamic tells the singer that it’s in a different mood than the flash of anger from the previous phrase. Whatever that change of mood means for you, there’s space written in around the second “Susanna” (which is misspelled in this edition, FYI); you can help make it heartfelt and organic by making sure the “Su-” is really sung. The strings will have a fairly slow attack on that piano chord, so you have time to give voice to that eighth note.

- This is another pivot moment in this recit, where the singer inspires the orchestra’s change from coy dotted rhythms (for her “ingenua faccia” and “occhi innocenti”) into blustering, masculine anger. Keep that in mind when you deliver the line, “chi creduto l’avria?” It should end with a kind of fire that lends itself to those forte chords that follow.

- For plenty of Figaros (Figari?), this high E-flat on “è ognor” can be scary. There’s technique to address, but it can be made easier by focusing on the complete sentence, rather than just one word. If you were to speak this line about putting your faith in women, you’d go all the way to “follia” rather than hovering over the “è” (“is”). You still need to sing the E-flat, but it’s not the crux of the sentence.

The aria

- Anyone who has ever sung this aria will tell you it’s all about pacing. It comes near the end of the opera, so Figaro has already done a fair amount of singing. As you start the aria, get your voice moving comfortably in this easy register; be sure not to confuse Figaro’s anger with vocally giving too much, too soon. These first couple of phrases are full of cynicism, but they shouldn’t cost you too much as a singer.

- These repeated B-flats tend to either get progressively flat, or they start to lose their vibrato and brilliance. Sing this measure like one long, sustained note rather than four.

- If you plan ahead, you won’t need to take a quick catch breath before the high E-flat. To give yourself the most amount of time possible for that big leap, take a good breath before “guardate cosa son” that leads into the measure before. You can also anticipate getting up to the E-flat; you’ll feel like you get there early, but you’ll have the time to sing that top note, not just touch (or yell) it.

- This is another spot where legato counts for a lot, despite the squareness of the rhythm. It’s really about being comfortable with the D on “Dee,” and that will come easily if the B-flats leading up to it are free and flexible. Check your progress on that long “a-” in “chiamate”.

- These large leaps are fun, but they can cost you too much if you’re not efficient. The idea is to stay up in the E-flat, D-natural part of your voice, and think of maintaining that height as you pop down to the low G, F, & E-flat. That D-natural that starts “la debole” shouldn’t feel like a reach; if it does, be sure that you’re not adding extra weight on the low F at the end of “incensi”.

- Another spot to coast. This is a good opportunity to dig into this great text. It’s in a comfy register and it’s not really a melodic section, so it’s not a place to spend on sound. The payoff will come later, I promise you.

- This B-natural on “civette” (meaning “hussy” or “minx”) is really expressive; you don’t have loads of time to do so, but add a slight tenuto on the “ci-” to help that “wrong note” stand out.

- These short phrases are leading towards the rest of this scary page of music; it’s another chance for you to conserve energy and concentrate instead on spitting out text. To keep it clear, I think it helps to add little tenutos on the B-flats, (“spi-” of “spinose,” “vez-” of “vezzose”, etc.).

- Have patience as you figure out your balance in these rising triplets. It’s worth keeping the text and singing separated for a while, while you get your tongue around all the Italian, and figure out the technical details you need to employ. In terms of the latter, break it up like coloratura, and imagine that instead of endless triples, you’re singing half notes (circled for clarity): two beats of G-natural, two beats of A-flat, etc. Figure out how you would sing this section if it were written this way, then slowly add in all the triplets, and finally all the text.

- You most likely need a breath around this point, and right here, between the two “non sentons” is really the only place that makes sense to do it. Singers never feel like they have the time to take a decent breath and then continue rising up through their (probably) passaggio. Will yourself to make time to get your voice really going on the “sen-” of “senton” on the high D, as well as the “pie-” of “pietà”. The same idea applies to when you’re finally up on the E-flat. It’s not an easy section, but stay patient. And bring it to your voice teacher.

- Singers breathe in different places around this section; the only place that seems to be a no-no, according to today’s performance practice, is between the last “no” and “il resto”, from the E-flat to D-flat (like with anything, you’re free to do whatever you’d like if you can sell it). The work is unfortunately not done after these exhausting few lines; that D-flat can’t sound like you’ve lost your energy and you’ve fallen down from the E-flat. Consider the whole line leading like a long pick-up to “il resto”. One more detail on that: instead of singing the L in “il resto,” it’s widely accepted instead to replace it with a second rolled R. So basically, “irresto”. Easier to sing up in that register, I imagine. Remember that Mozart writes this section twice. Talk about pacing.

- It’s common to take a brief pause before coming in again with “aprite un po’…”. Plenty of Figaros like to take a moment to breath, swallow, reset.

- More coasting; back right off to help you recharge for trickier things to come. You can play with the repetition of the text, which is about my favourite thing in the world, subtext.

- This is another spot, like earlier in the aria, where you want to be wise with how you spend your voice. Mozart has you alternating between higher, more feminine gestures, and the low-pitched barking on “il resto nol dico”. Unless it’s a natural tendency for your voice, there’s no real payoff in trying for more sound on the low B-flats. The notes are important, but it’s more about a grumbling Figaro getting comedy-angry.

These little mini phrases can have a parlando feel to them, like you’re telling the moral of a story. Do take the time, though, to sing both vowels on the C-natural, “già” and the “o-” of “ognuno”.

Set yourself up to sing, not shout, this last declamation by vibrating on the eighth note pick-up. You can even start the “già” a tiny bit early in this case, so you can finish this beast of an aria with Figaro’s most triumphant, virile sound. He’s got to seem a worthy opponent to The Count, and that means maintaining vocal control until the end.

For good measure, here’s bass-baritone Luca Pisaroni singing “Aprite un po’ quegli occhi” in Emilio Sagi’s production of Le nozze di Figaro at the Teatro Real Madrid, 2009, conducted by Jesús López-Cobos.

Comments