Aria guides: Dido's Lament

How-ToFor our latest Aria Guide, we’ve picked an aria that has it all: it’s beautiful, it’s in English, and mezzos get to play Dido, an actual woman. In Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, “Dido’s Lament” happens at the end of a simple and sad story: Aeneas, whom Dido loves and has agreed to marry, believes he has to leave her and go to Italy. As he goes, Dido dies from her grief.

It’s pretty operatic, sure; and Dido’s Lament is more difficult than the simple-looking score suggests. Along with your teachers and coaches, there are a few we can offer, to give you a head start on this sob-fest of an aria.

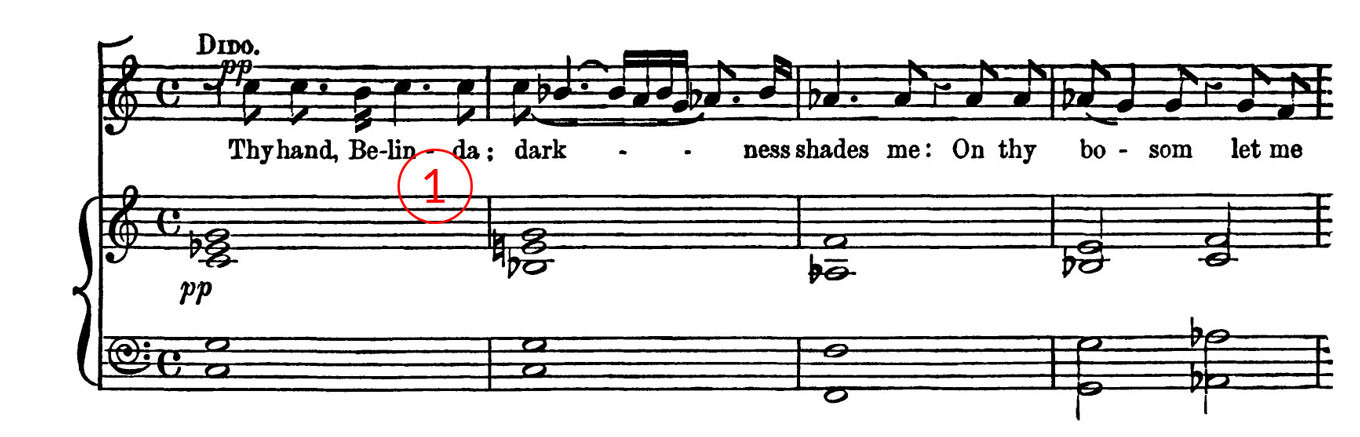

- Purcell gives you plenty of freedom in this recit, but there’s direction in the slow chord progression he lays out. You can play with the great tools he gives you on the word “darkness”; keep in mind, though, that the word is only part of a larger sentence. Whatever you decide to do with “darkness”, let it continue to “shades me”. One detail on the A-flat for “shades”: some editions show the flat as an option, the other option being an A-natural. There are cool layers of subtext to find by singing an F-major triad under these words, in case you’re curious about more colours.

- Don’t neglect the word “more”; it can get lost in the rhythm, but it’s a meaningful little word. On the word “Death”, find a text-based reason to sing two notes. There’s something ominous about moving down a semitone; maybe it’s a jab of pain, maybe it’s Dido growing light-headed.

- With all the drama infused in this “Death is now a welcome guest”, the trick is to avoid belabouring every detail; keep speaking the full sentence to yourself, to stay connected to the natural pace of the language. If you take this line literally - a good place to begin - it’s simply good news; by bringing out the happiness in “welcome guest”, it lets the audience feel the gravity of Dido’s words. Finally, don’t feel rushed to sing that sneaky tritone at the end of “welcome”; it’s a musical device packed with meaning, and Purcell seems to want you to enjoy the journey of that interval, not just the destination.

- Gah. So much empty space! The trick to this aria is like any other slow piece of music: try singing it way too fast. It’s slow, but with anything in triple metre, there’s always a broad feeling of one beat to a bar. It’s easier to find this larger beat at a faster tempo, and if you remind yourself of that big picture once in a while, it keeps you from working too hard. The first example is in these first two bars; “When I am…” leads right to “laid”, just like it does in speech.

- If you can make it through “may my wrongs create no trouble”, that’s a big bonus. It’s not obligatory, but it’s totally possible with the right breath management. Whether or not you take a breath before “no trouble”, consider the two E-flats as one long note to make them easier to sing through. Purcell gives you another meaningful tritone on “trouble”, so take the time to enjoy it.

- This “trouble in thy breast” line happens twice; each time, pay attention to the length of the word “breast”. The note is longer than you’d think, and it’s really effective to hold it to its full value, and pass the tune along to the orchestra. For all iterations of “Remember me”, roll the R on pitch, and find a vowel in the [I] vicinity for the first syllable. (English diction experts may disagree with us, and there are likely a few right answers; our only real problem is with “[ri‘mɛmbə]”.)

- If there was ever a case for a portamento in Baroque music, it’s on this “ah!” On the repeated C-naturals on “forget”, try not to overthink them as two separate notes; if you think of tying them together, you get a cool, slow syncopation over the whole bar. For the big “remember me” on the high G, let the D-natural pick-up help you. Find a version of that [I] vowel that has enough space for the leap up, and let it spin right to the end of the bar. If the first M in “remember” gives you grief here, you can think of it more like a B, and sing a longer vowel before it. Finally, sing that last “fate” to the bitter end of its bar, like Dido doesn’t want to give it up.

Comments