Aria guides: La donna è mobile

How-To

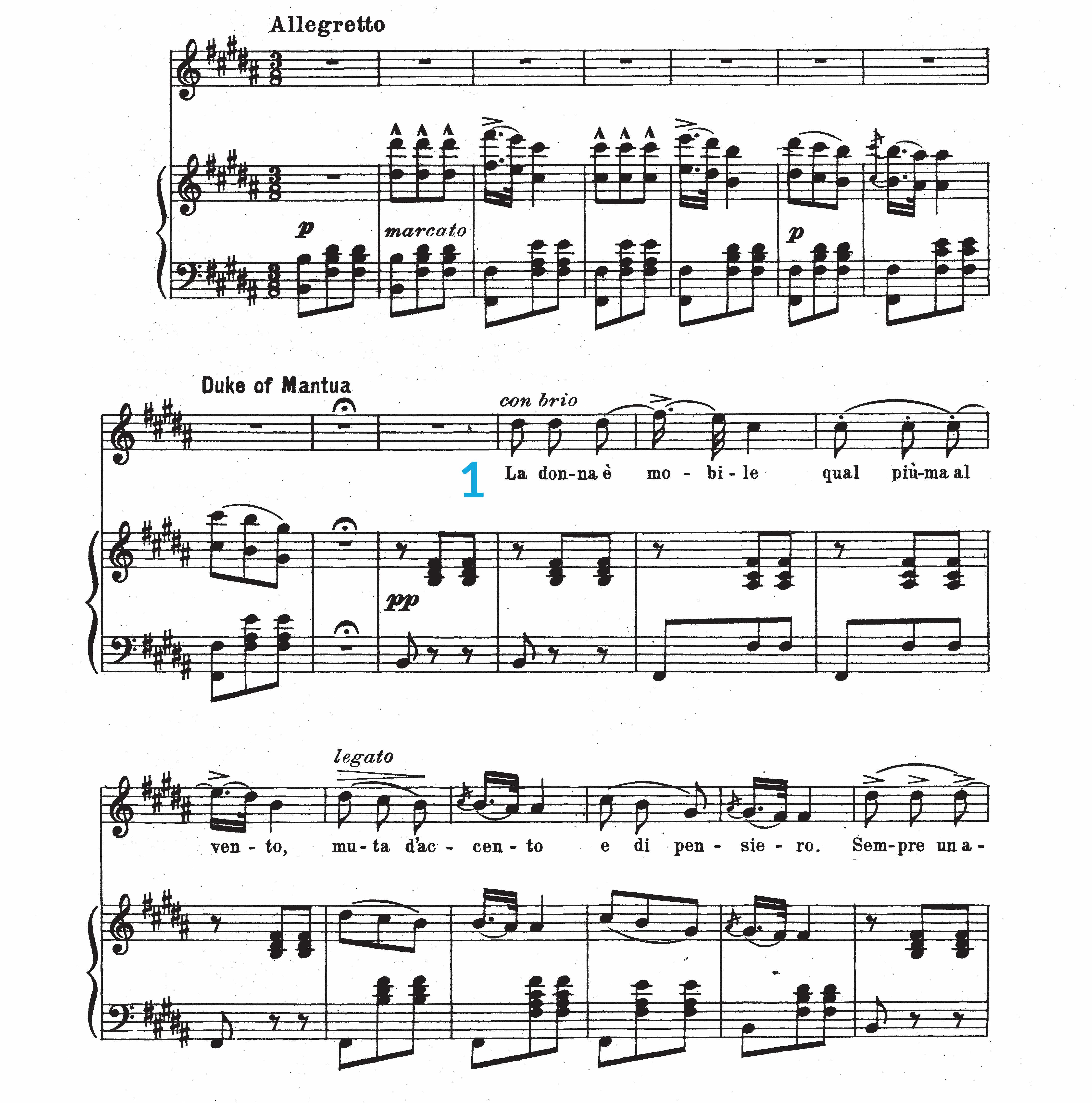

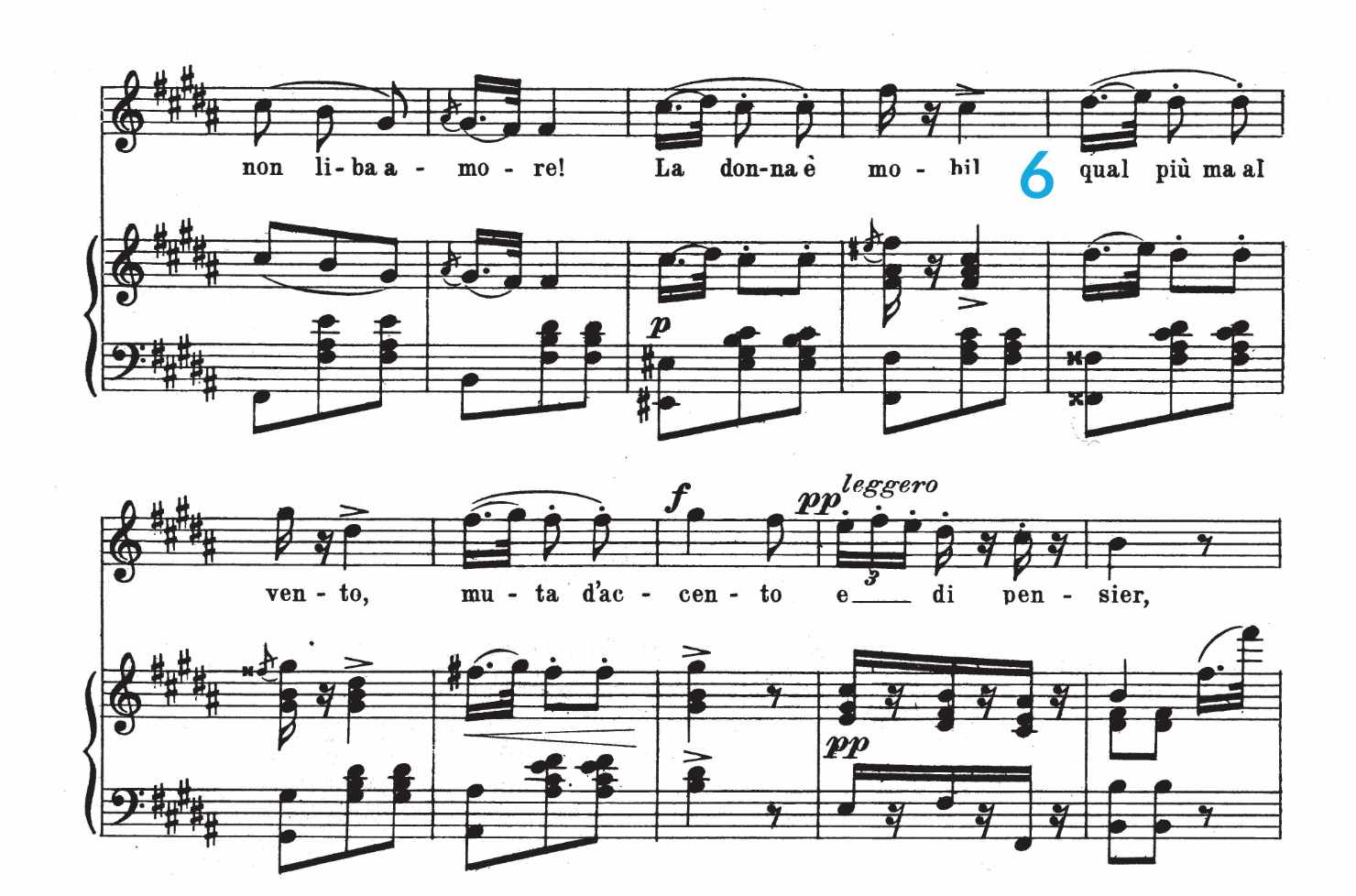

When music is written in 3⁄8 time (1), it nearly always has a big feeling of one beat to the bar. Keep that in mind throughout this aria, because it will keep you looking at the big picture. (Hint: the first sentence actually continues all the way to #2 below.) Let the first bar feel like a pickup to the next bar, and so on - and when you sing that fun little portamento on “è mobile”, let it shoot you forward to the next downbeat. With all the square, simple phrasing in this aria, contrast will be key to keeping this interesting: Verdi starts you with con brio (and hopefully, legato), then asks for crisper text at “qual piùma”, then explicit legato at “muta d’accento”, then with some virility at “Sempre un amabile”. The many faces of an insufferable Duke.

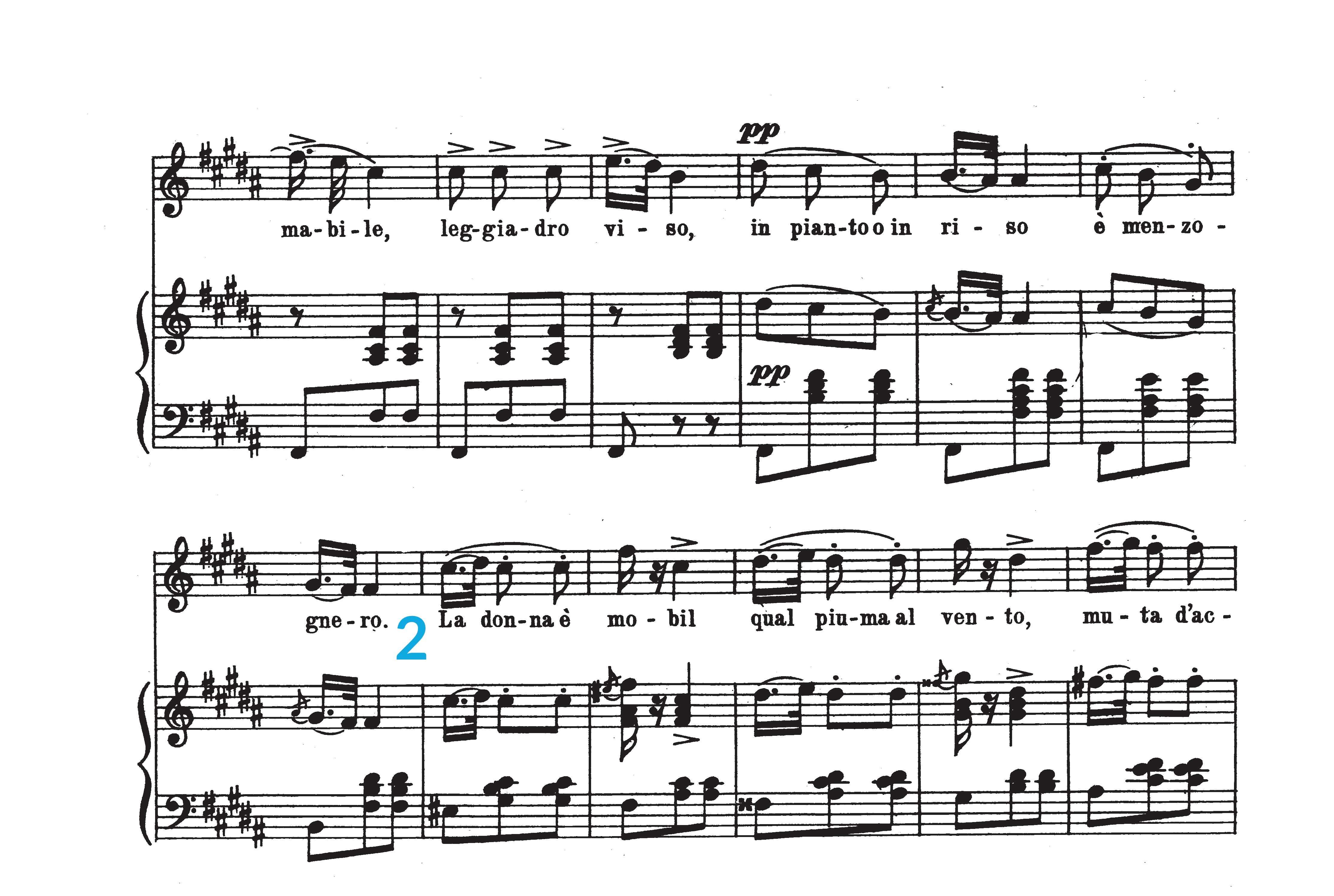

This bit (2) is tricky because you have to balance the short note value on “mo-bil”, with actually singing it. In the practice room, take out the rest and get used to how this phrase feels; then add in the rest gently, taking care to keep “mo-” spinning, even if it’s short. And just over the page, below at “muta d’accento”, it’s common practice to take time on “-cento”, and then snap back into tempo at “e di pensier”.

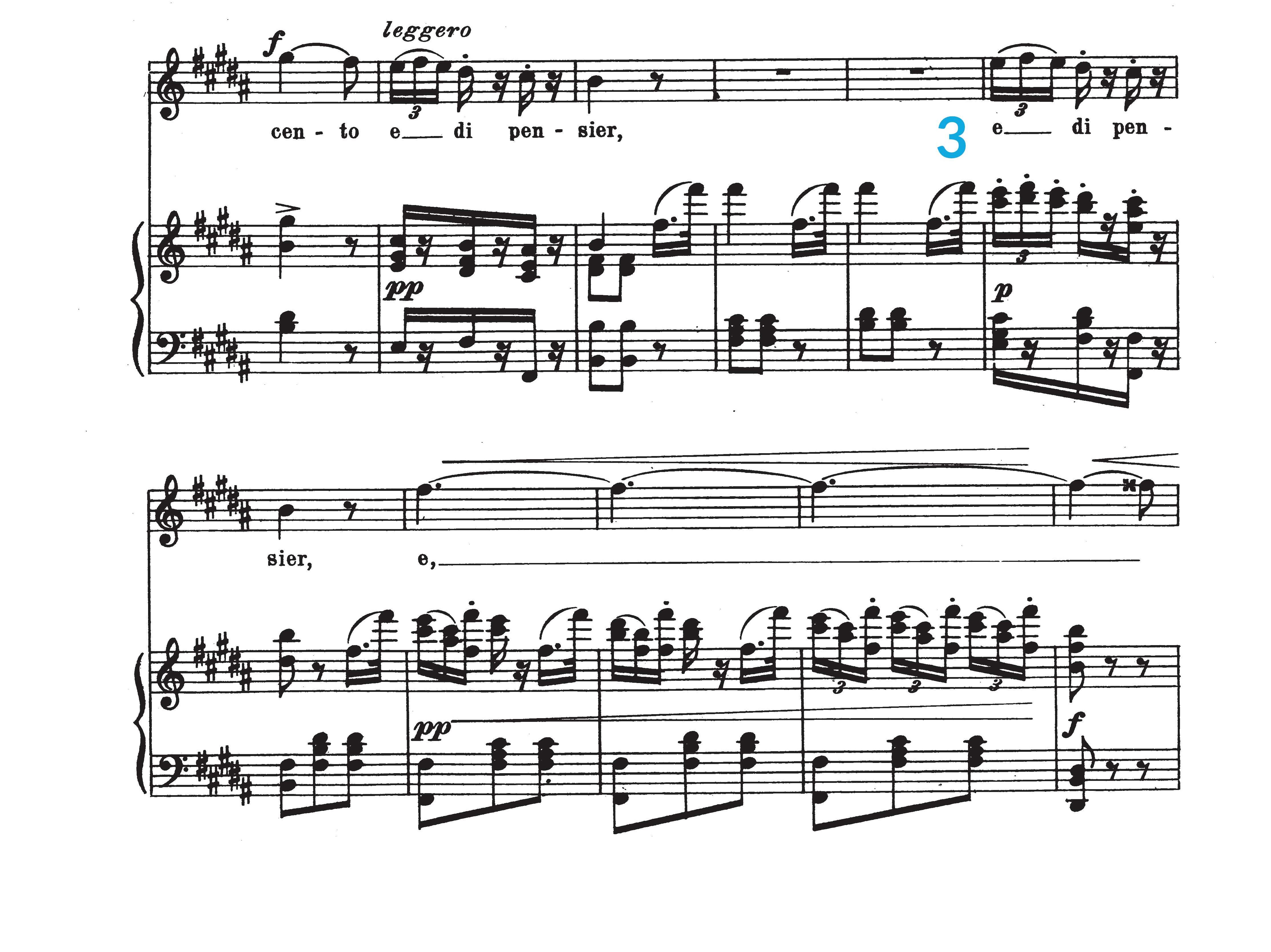

Plan your breathing here (3), so you don’t tank up too soon. You’ll need your best breath for the long F-sharp in the second line here, so plan for just a sip of air before “e di pensier”. For the long F-sharp itself, work with your teacher to pace that crescendo, and keep your [e] vowel working for you. Verdi gives you a valuable tool in that extra crescendo on the F-double-sharp - it should help you over the A-sharp below.

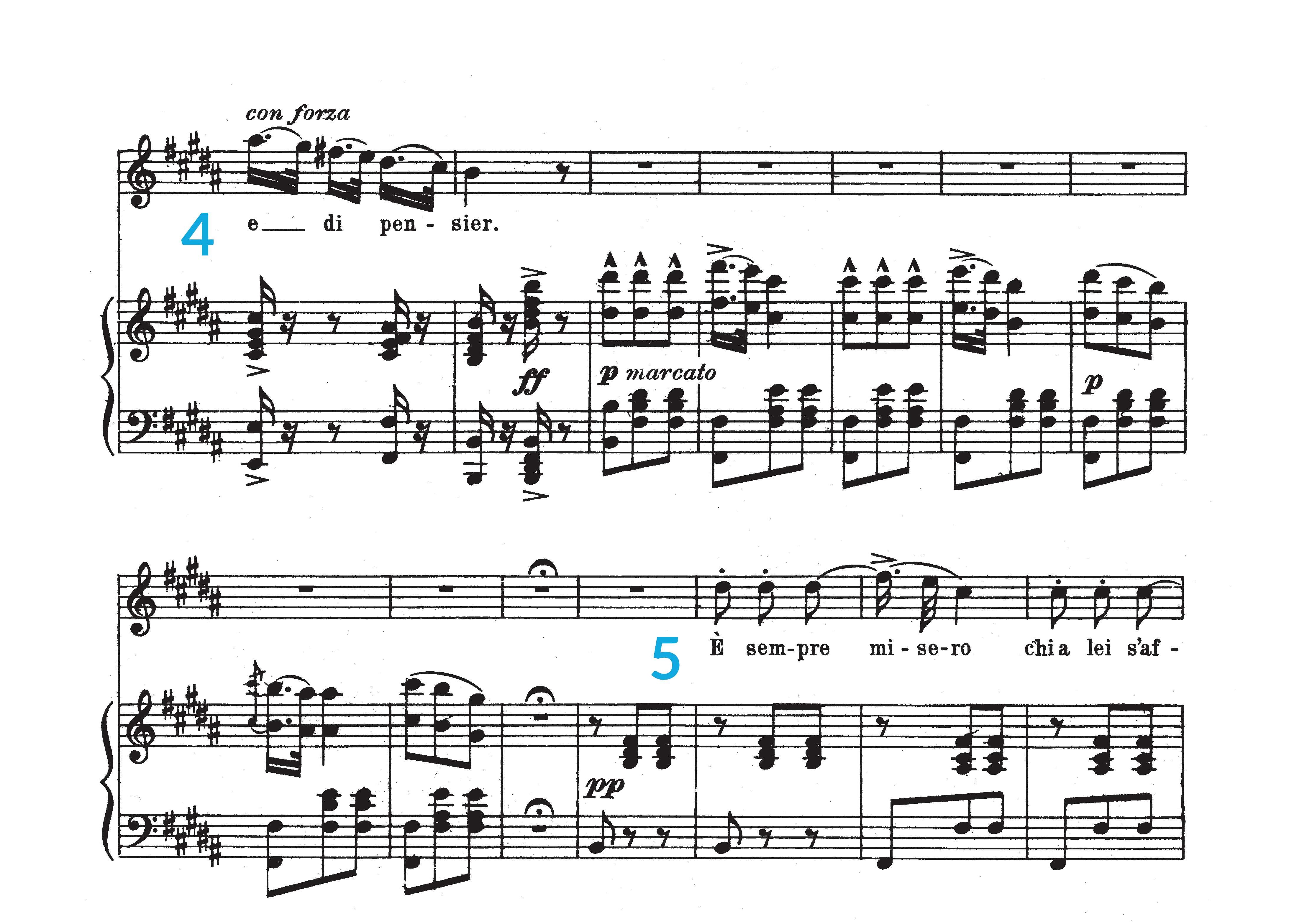

Practice this bit (4) without the dotted rhythm, to make sure you know where the short notes live in your voice. It’s oddly common for tenors to end up flat on the B, and then the orchestra’s chord comes in sounding slightly funky. Try to think of this phrase moving forward, not downward.

I’m skipping a bit of the second verse here (5), but the aim is still about contrast. There are subtle differences in articulation here, like the staccatos on “È sempre…” and “chi a lei…”, so really show those differences here.

Same section, same trickiness (6): just make sure that you’ve got something a bit different up your sleeve for how you approach “d’accento”. You can stretch this out in both verses, but find something new about the second time. Maybe the staccatos on this “e di pensier” are a laugh.

Same as before (7): save your big breath for the long note. There’s a common cadenza that gets plugged into the penultimate bar, with a long melisma that leads to a high B at the end. Like with any cadenza, you should feel free to experiment and show off your voice’s best qualities. I’d say that a high B at the end has become an industry must-have. The last detail is in coordinating the last “pensier” with your pianist or conductor. One good answer is for the F#7 chord to go in between “di” and “pensier”. Others like to be in unison for “pensier”, which is cool, but slightly more risky. Listen to a few options, decide what works best for you, and then be prepared to adapt. (Conductors, right?)

Ready to hear the finished product out loud? I really do love Pavarotti’s rendition from the 1987 film production of Rigoletto, where his eyes are staring into your soul. But for something a bit more dramatically interesting, have a look at Vittorio Grigòlo’s earnest, unsettling rendition in David McVicar’s production at the Royal Opera House in 2017:

Comments