Aria guides: Parmi veder le lagrime

How-ToThe Duke of Mantua in Verdi’s Rigoletto is one of opera’s most coveted roles - even though he’s an utter ass: Entitled, lying, and never properly repaid for the bad karma he spills out into the world. To sing the role is no easy feat, and there are delicious dramatic layers in the Duke that challenge a tenor to find beauty in a villain’s thoughts.

In this aria, the Duke is angry that Gilda, the young woman he lied to in order to get into her pants, was kidnapped (by other terrible men) before he could actually seal the deal. That’s right: Gilda’s kidnapping is bad for him.

The Duke is a tricky character, and this a tricky aria. Along with the work you’ll do with your teacher and coach, we can help you get started and avoid any energy-sapping traps in this score.

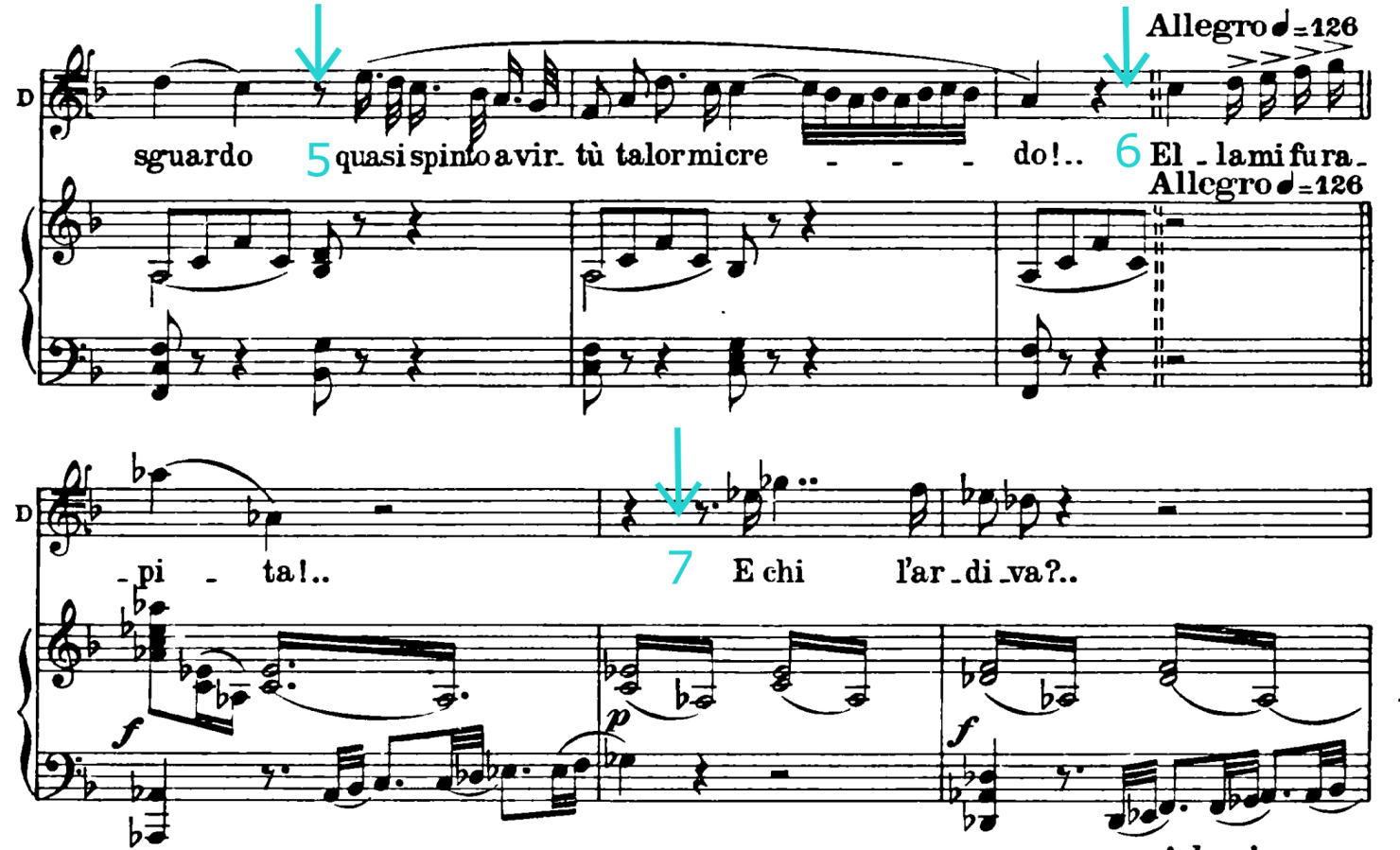

- The rhythm here (1) is about anger. Yes, we’re in a recitative, but Verdi’s recits still have tempo. It’s always a fine line between observing rhythm and giving priority to the text, but I find a good middle-ground is to consider proportions: let us hear the difference between a sixteenth note and a quarter - like in this first line - and you’ll find something organic and true to the score.

- Take a smart breath here (2), and give these notes room for vibrato - particularly the first high G.

- This D pitch (3) that you keep repeating - it turns into something new when the orchestra comes in on “sa-rà”. Check your intonation on the E of “quell’”, and sing through both Fs in “angiol”.

- Try not to over-think these phrases (4). Verdi writes you a crescendo and diminuendo over your line, so let those help you up and down this tricky stepwise motion.

- There’s a mood change here (5), when the Duke recalls how Gilda looked when he met her. Keep it light, and don’t get caught in the trap of equating dotted sixteenth notes with a fast tempo. When you get to the long melisma on “credo”, maintain your vowel.

- Everyone will have their two cents on how to interpret all these accents (6). Some argue it’s about crisp text, others might say it’s about giving a rhythmic lead-in for the orchestra. In any case, they’re a bit odd to sing, even unfriendly to the voice in that run up to a high A-flat. Pay attention to the first C-natural, and note that it doesn’t have an accent; it’s a great way to start this phrase lyrically, without hammering right away.

- Be picky with intonation here (7). It’s easy to throw away that tiny E-flat, and even easier to be flat on the F of “l’ardiva?”

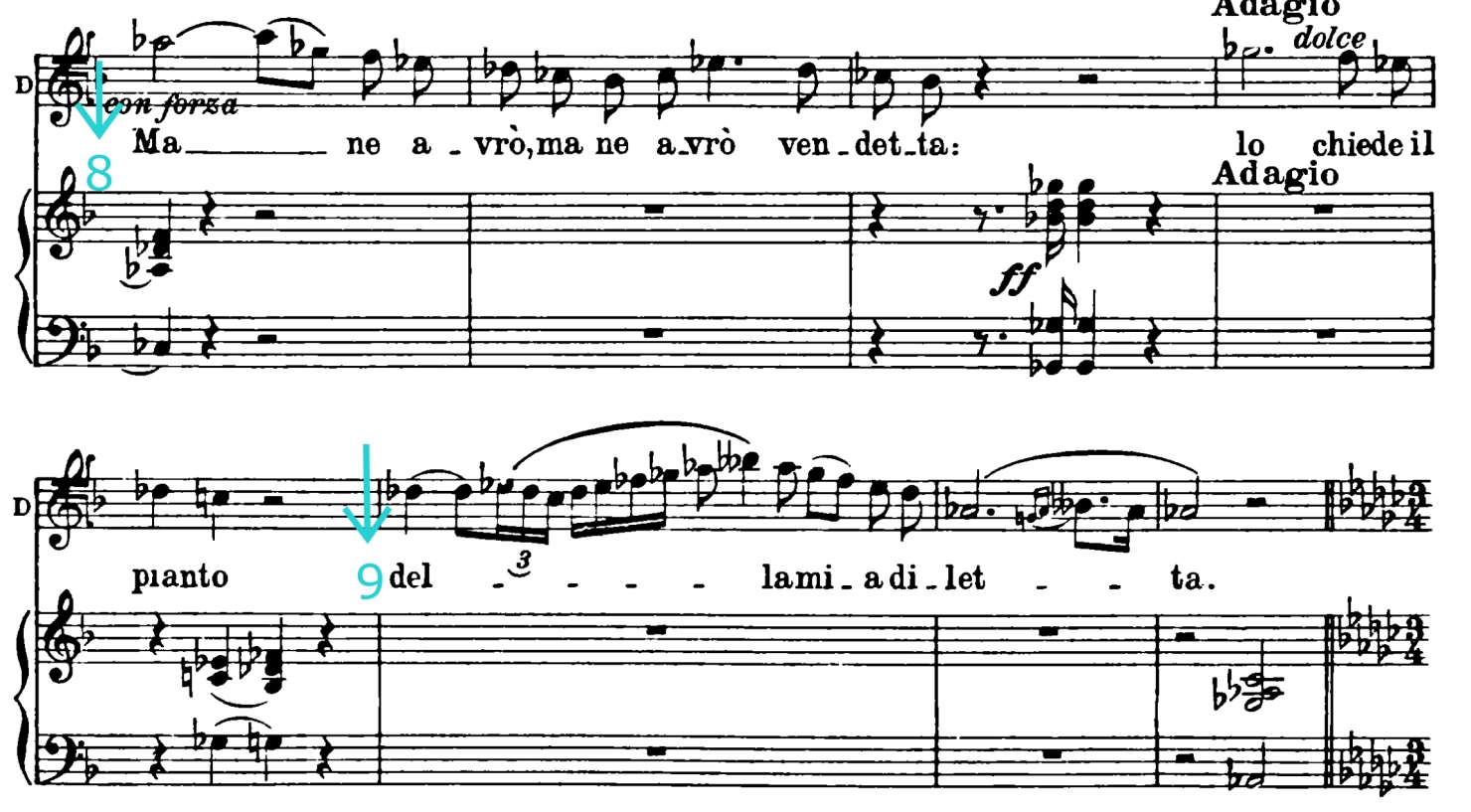

- It’s easy here (8) to focus on the A-flat, and consider your work done once it’s over. The whole line needs care, and it starts with maintaining spin and vibrato on the G-flat, where you first start your descent. The step should be legato and still in tune, both good signs that you’re keeping your energy up for the full phrase.

- This melisma (9) is certainly one to take to your teacher; different tenors will find their favourite vowel, both at the start and to modify up at the top. The tricky bit, of course, is the semitone between the A-flat and B-double-flat. It will feel quite wide, even for a half-step, and maybe it’ll even feel like you’re moving from one “place” in your voice to another. A good marker of a job well done: you can still vibrate on the A-flat on your way back down.

- The aria finally begins! (10) Verdi gives you plenty of chances to stay legato - the portamentos between “Par-mi”, “scorren-ti” and “…ciglio, quando…” - but the trap is to set too slow a tempo. Every so often as you learn this, it’s helpful to practice this aria too quickly. A fast tempo, even one faster than you plan to take, will remind you that this has a triple-meter, dance-like feel to it. There’s tension written into these phrases, and if the aria is too slow, that tension turns into shapeless slack.

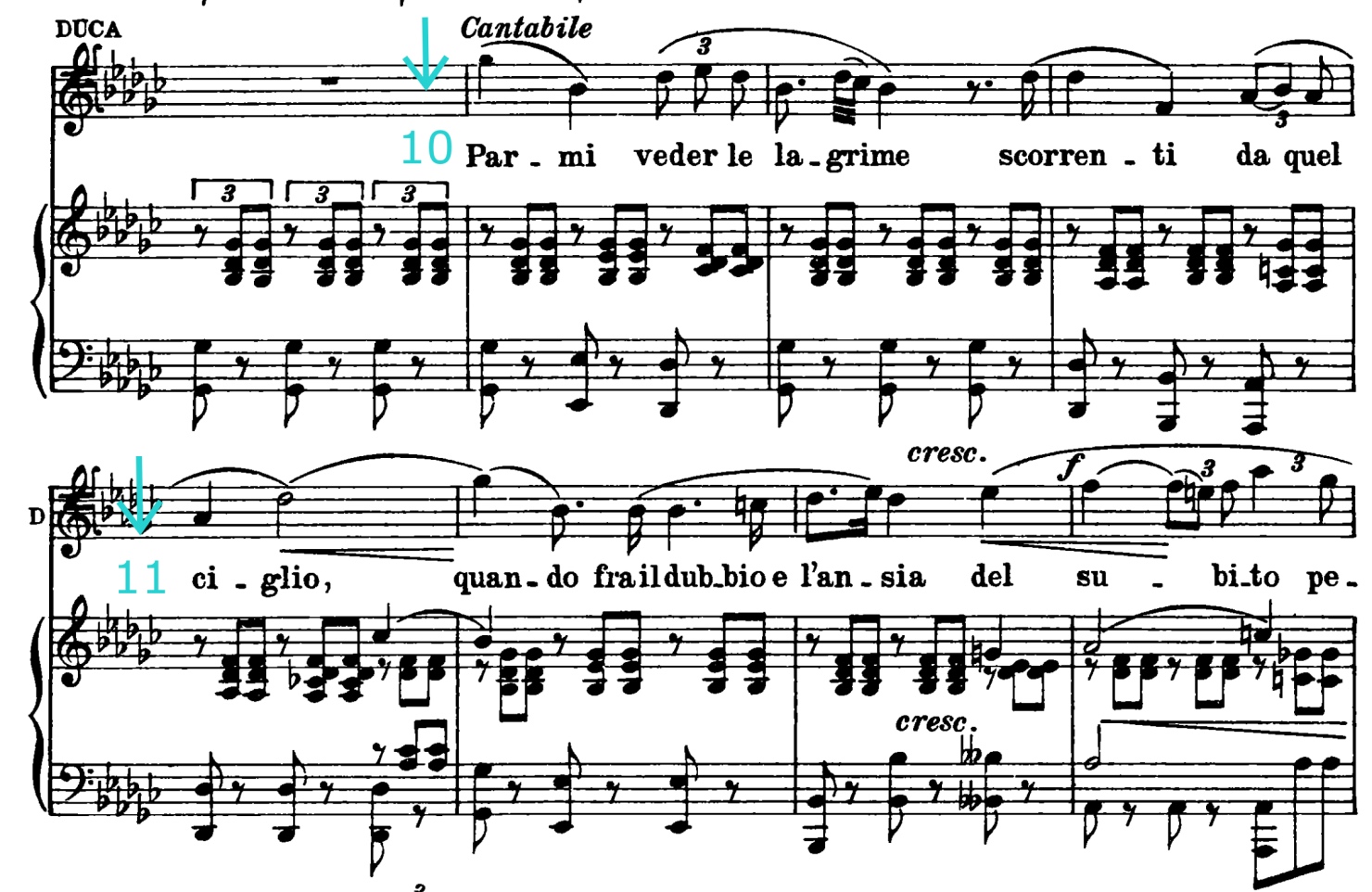

- This upward portamento on “ciglio” (11) is all about planning ahead of time. Essentially, you’re heading back to that G-flat from the very start; if you’ve let your resonant space drop in the first four measures, this will be more difficult. Backtrack a bit to “scorrenti”, and take care that the portamento down to the low F doesn’t cost you your upper resonance. The crescendo marked on the way up to the G-flat is really more of an allowance than a direction; the voice will automatically get louder with this rising portamento, and the whole thing will be easier and more beautiful if you let that happen. Verdi’s not asking you for more sound than you’d naturally make in this part of your voice.

- For what it’s worth, I’ve never heard anyone sing this ossia option (12) - stick to the main line unless asked otherwise by a conductor. This is a rhythm-centric section, contrasting with the lyric lines that precede it; the orchestra shouldn’t have to wait for you until the fermata at the end of this line. You can be expressive while staying in tempo; Verdi even helps you do that by allowing you another crescendo up to the high A-flat.

- More lyric stuff here (13), and in a tricky spot of the voice. You’re aiming for a new colour here, but nothing more quiet than you can comfortably handle. Be careful not to completely relax after “soccorrerti”, or your second set of F-flats won’t be in tune and that triplet on “fanciulla” will be hard work.

- These few bars (14) should have a sense of moving forward; that’s a good thing, because there’s something cruelly incessant about this transitional phrase. Consider where you’ll breathe, and where you won’t - particularly since your tempo might be slowly increasing. If you get a good breath before the first “ei che le sfere”, you might be fine to sing through the first “per te”, before breathing again in the common before the A-flat. And one bit of performance practice: in the last “angeli” before the fermata, many tenors show off by trading the G-flat for a high B-flat instead.

- Of course, this (15) is a spot to work on with your teacher; and if you’re working with a conductor, they may have some wants and needs as you pace out this cadenza. Two big things to keep in mind: don’t let yourself fall into your vocal basement as you come down on the first “non invidiò”, and begin the melisma in an [a] vowel that’s tipped forward and ready to serve your coloratura.

Some old-school mastery of this aria, courtesy of our friend, Pavarotti:

Comments