Aria Guides: Quando m'en vo

How-ToFor our next instalment of Aria Guides, we’re sticking with the tried and true pick of divas around the world, “Quando me’n vo” from Puccini’s La bohème. It’s got everything you really want in an aria: girl tries to make her ex-boyfriend jealous, and she does it by singing sexy lines and shimmering high notes. The basics of this aria are really about great technique and great rhythm, and your voice teacher is the one to ask about the former. This guide will help you keep the easy stuff easy, and get you to a place where you can bring Musetta off the page.

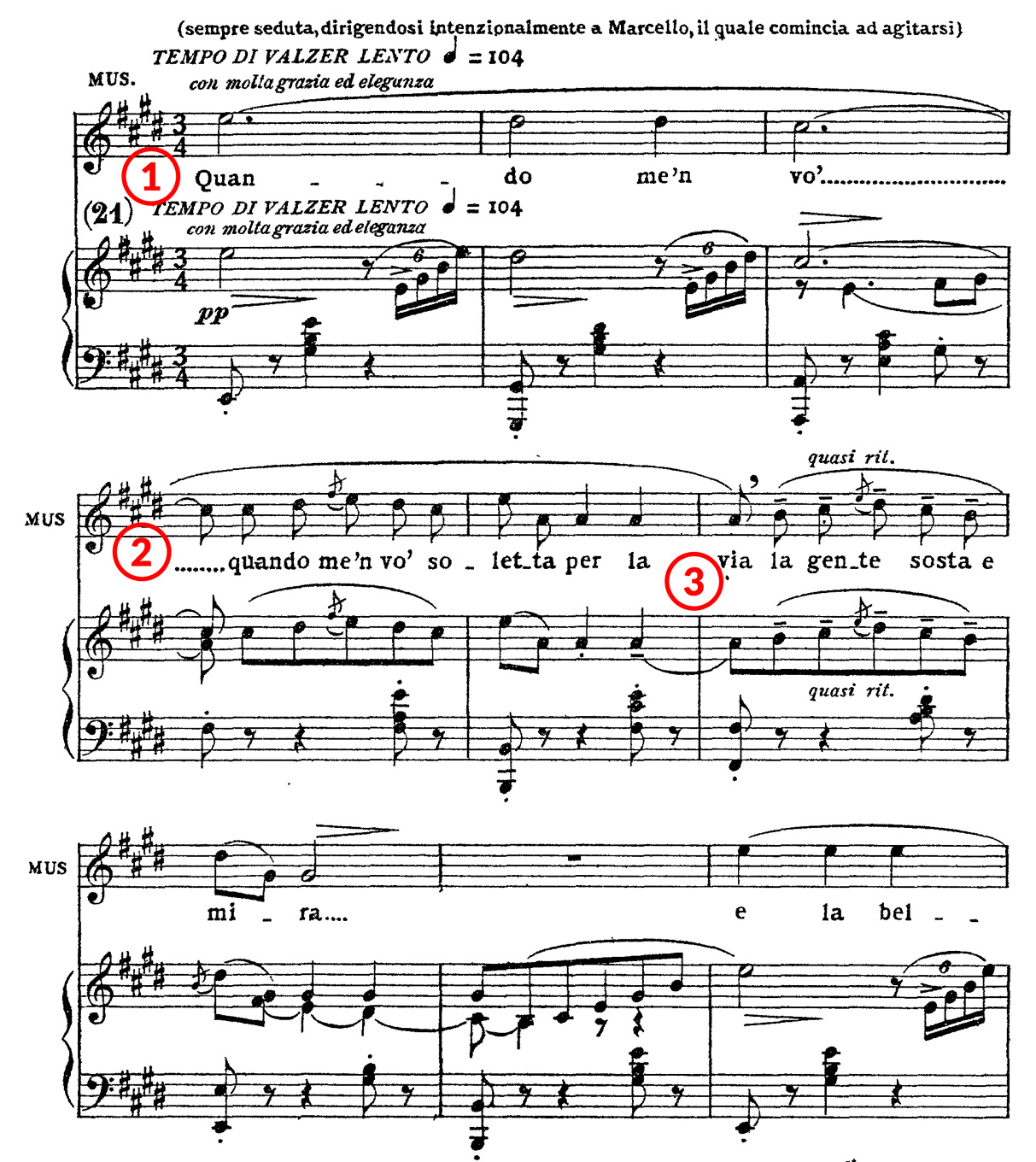

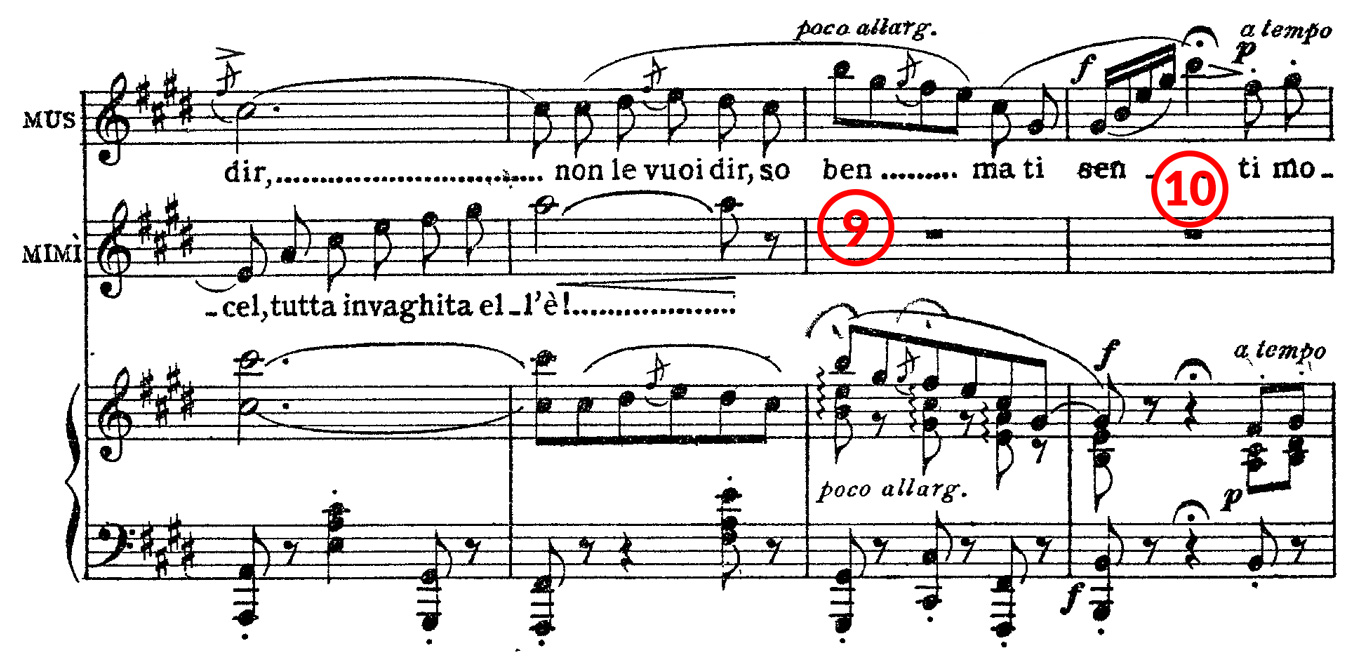

Follow along with the excerpts below, or starting on page 129 of this score.

- The very first note of “Quando m’en vo” is fairly exposed for the soprano, who’s expected to produce an endless line of stunningly beautiful sound. One simpler way of looking at this phrase is thinking of the first two bars as a pick-up to the third. An Italian speaking “quando m’en vo” would naturally move towards “vo’”, so it’s not far off from what the text wants. Imagining an extended pick up is a way to avoid landing heavily on downbeats, and it’ll open up more technical possibilities for you colour this first phrase. For the full legato experience, sing through the letter N in the words “quando” and “me’n”; you can afford more of a double-consonant effect in these spots, which will encourage you to maintain pitch and vibrato into the consonants.

- Be diligent with the grace note in this phrase (and the others in this aria), and be sure that the grace note pitch is truly in your voice. Practice it slowly and out of metric time, to get your body to treat that F-sharp like an honest-to-goodness note, and not a passing squeak. You’ll be able to adapt easily to various conductors and their various tempi.

- Here’s an example something that comes up a few times in this aria (the whole opera, really): the fluctuation in and out of a ritardando. Considering that the orchestra has to fluctuate along with the soprano, it’s wise to look at these ritardando bars as more mathematical than intuitive. Practice your pacing by tapping sixteenth-note subdivisions; it’ll lessen the margin of error, and the ritardando will be truly gradual. It sounds unimaginative, but it’s ironically the only way a full orchestra can “do rubato” together. In short: if you can conduct it, you’re good.

- This is a similar moment, since appena allargando is close in meaning (for all intents and purposes) to quasi ritardando. The same math-like approach works here, subdiving in sixteenths. Keep in mind that when you see the tempo indication, it means you’ve only just begun a gradual effect. So here, “tutta ricerca” at the top of the page should still be pretty much a tempo. The breath you take after the allargando, before “ricerca in me da capo a piè,” should be right back in time.

- This section broadens in tempo, and I interpret the sottolineando marking to mean that Musetta is laying it on thick in front of Marcello. Sopranos, take the time you need to find the right warmth in this low bit; it’ll also give you a chance to enjoy these sexy words. Sing through the double S in “assaporo” to help you vibrate on every note; you’ll want that kind of legato when you get to that amazing portamento on “…poro”.

- This is a weird area for tempo markings. There’s a ritardando marked right after a molto rallentando, plus stentando (holding back) for good measure. There’s some sort of an implied a tempo after Musetta sings “traspira,” so be careful not to schlep as you begin the next phrase.

- That little diminuendo over the word “beltà” can be pretty hot if you let it. The rallentando in that bar lasts until the very end of it, including that last eighth note in the bass. So, you’ve got plenty of time to add a little tenuto on the “bel…”, and then make everyone wait (a little bit) before letting go of the “…tà.” It’s an unofficial rule that singers who milk great moments in their arias have to give back somewhere; in this case, it’s not being late on the next, “Cosi l’effluvio…”

- This part always felt a bit like a mating call to me. That espansivo marking means you should enjoy the “fe…” of “felice” and “mi” in “mi fa,” singing those eighth notes like you have all the time in the world. (I bet Musetta is always ten minutes late to stuff.)

- There’s a funny tendency for some sopranos to sing an extra note in this bar; it’s easy to replace the G-sharp grace note with a little two-note mordent (F#-G#-F#). You may like the mordent better, and a conductor may even agree; for auditions, competitions, first sing-throughs, it’s wise to know you can sing what’s written, just to be safe.

- The big finish! This is definitely a get-thee-to-thy-voice-teacher moment, but I can offer advice for the scary diminuendo on the high B. Rather than trying to create a smooth, turning-down-the-volume effect, think of the diminuendo in dynamic tiers, or terraced dynamics. Figure out how loudly and how softly you’re able to sing the high B, and then imagine that you’re singing the note forte, then mezzoforte, mezzopiano, piano, etc. You’ll have lots of control over what you do up there, and your listeners will still hear the effect as gradual.

Comments