Aria guides: the Count's Aria

How-ToWe’re continuing our new series of Aria Guides with more Mozart, this time for the men: baritones, it’s your beloved Count’s Aria from Le nozze di Figaro. Like all you aspiring Counts, I too love this aria to bits. It’s got a recit that’s both textbook and full of life. The aria is wild soliloquy, full of unnatural mood swings from a powerful man who realizes that he can’t buy intelligence.

Follow along with the score excerpts below, or start on page 139 of this score. To request an aria guide, send us your suggestions! Get in touch at [email protected].

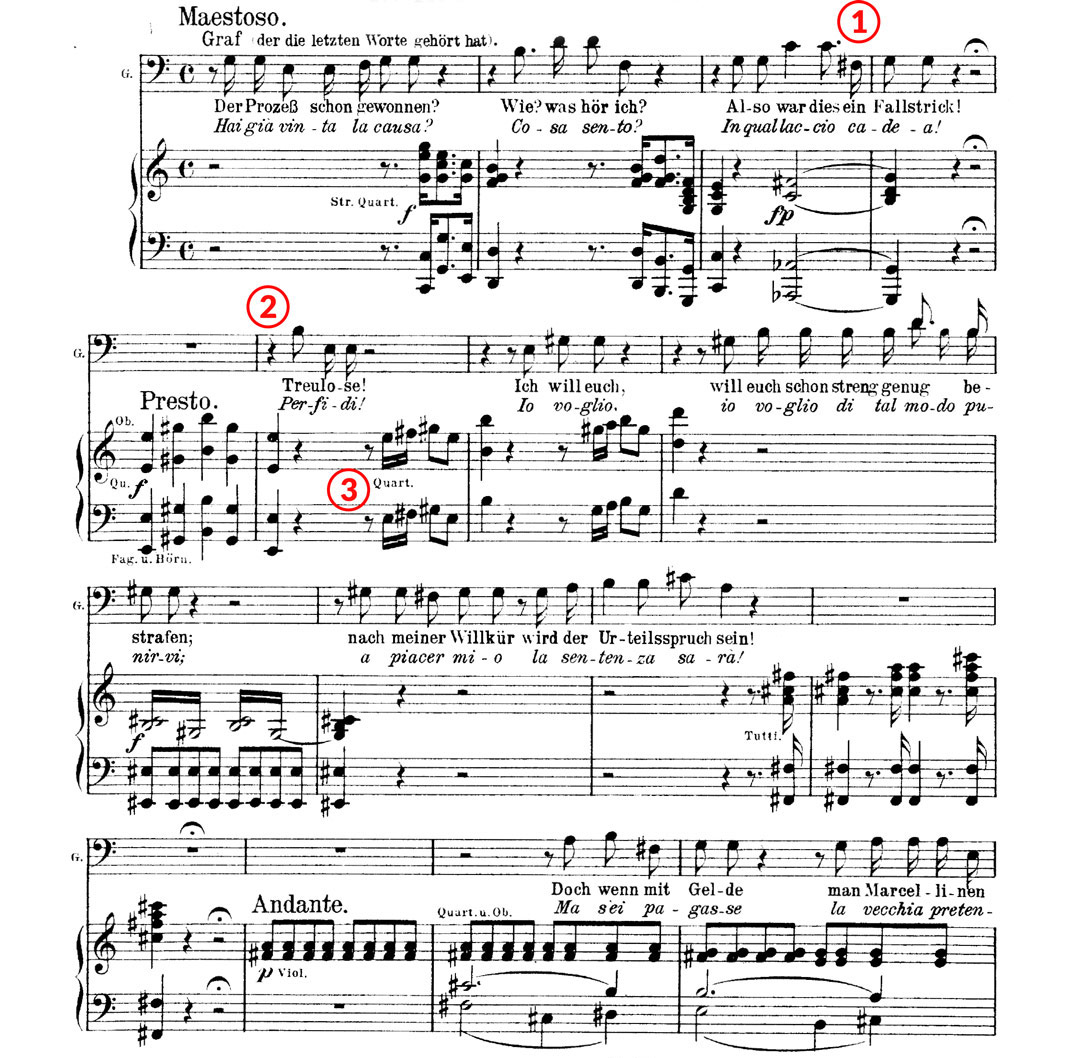

The Recit

Baritones can find endless ways of delivering the lines in this recit; I’m likely to buy a lot of them myself. I find this recit to be a balance of speaking and singing (and some shouting); the only real “rule”, in my opinion, is to find the important musical corners, and maintain some vocal integrity. To sum it up: sing first, and the drama comes out of that.

- Pay careful attention to the F-sharp in the word “cadea”; it’s often a little flat, so be sure that you’re singing a proper “ah” vowel, despite its being a short syllable.

- At “Perfidi!” you may want to shout rather than sing; that’s fine, but you really should know what the written note sounds like in case anyone ever asks you to sing it.

- Starting at the presto, I think the orchestra’s music is what starts most of the Count’s thoughts. Baritones, keep this in mind as you choose how rhythmically flexible your lines will be. For instance, taking a lot of time before saying “Perfidi!” or even “pagarla?” later on, doesn’t really work. The sentiment has begun in the music, and there’s no need to screech to a halt. Think of your lines as truly joining an ongoing idea.

- The line starting “E poi v’è Antonio” is a total stuttering mouthful. You have more time than you think to deliver this text; it helps to ground yourself with the word “incognito,” for starters.

- Be very clear about the intonation of the C-natural in the “tutto gioia” line. It’s important to set up the C-sharp that’s to come.

- “Il colpo è fatto” is a great line to deliver, no doubt. Be smart and tasteful about how long you sing “fatto.” Musically, there’s nothing stopping you from holding “fa” for as long as you like; before you do that, remember that “fatto” has short vowels by nature, and there’s only so long you can hold a word like that before losing its meaning. Besides, you’ve got a whole aria to sing.

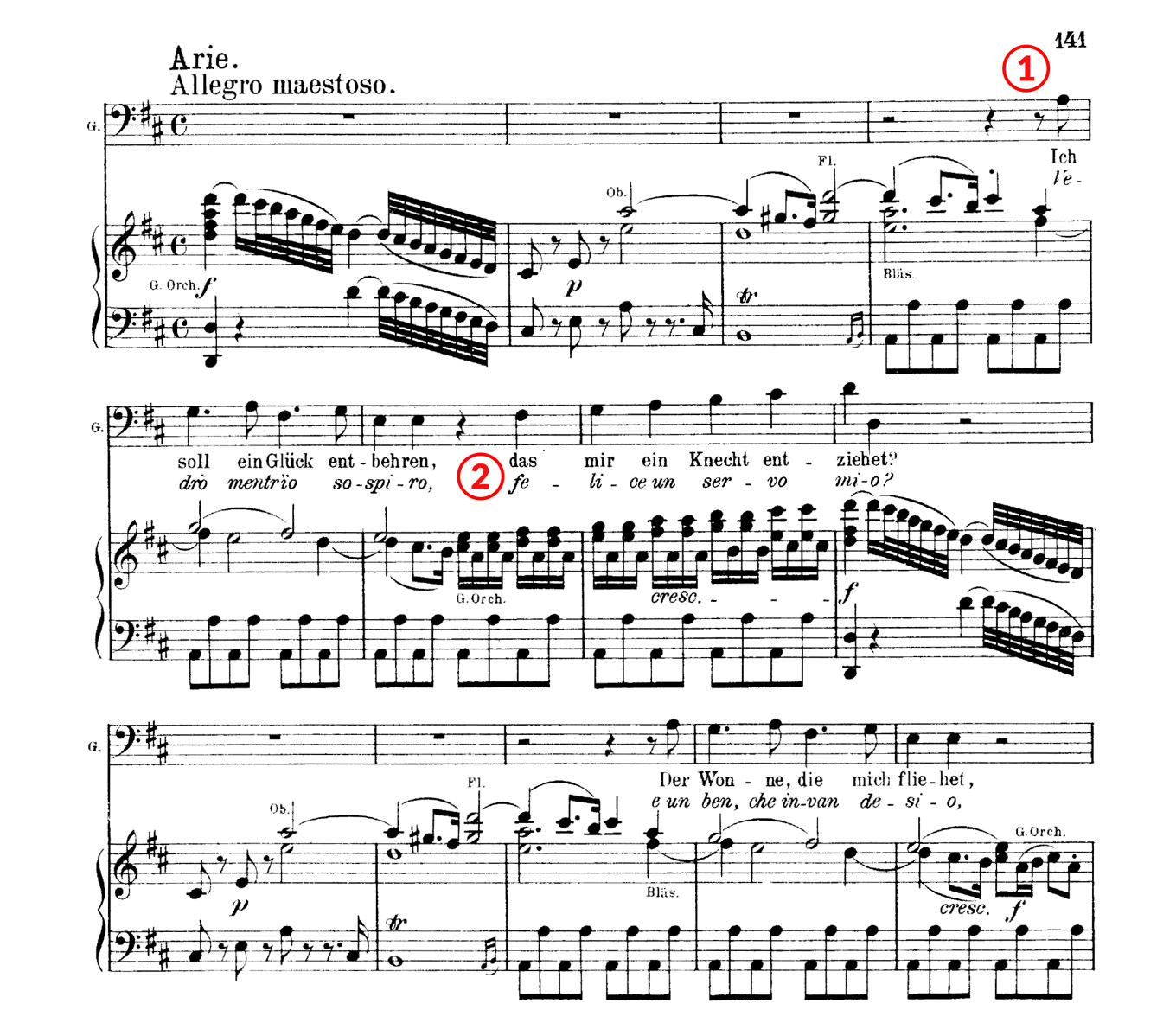

The Aria

- Like the balance of speaking and singing in the recit, this aria is about balance, too; it’s about balancing the Count’s schizophrenic rage with decent singing. A good place to start is with the recurring figure at the top, under “Vedrò, mentr’io sospiro”. The shorter notes need a bit of a tenuto attack, full of vowel; it may feel like you’re limping a bit, but without the extra care on the eighth notes, they’ll sound clipped and not sung, especially in a larger space.

- The short scale up on “felice un servo mio” is one of those tricky anger-vs-singing spots. Make sure the “fe” of “felice” is vibrating nicely, and find the bel canto, legato singing available to you on the way up to the high D. Pick a smart, ringing [i] vowel for “mio”, one that leaves room for confident, Count-like sound.

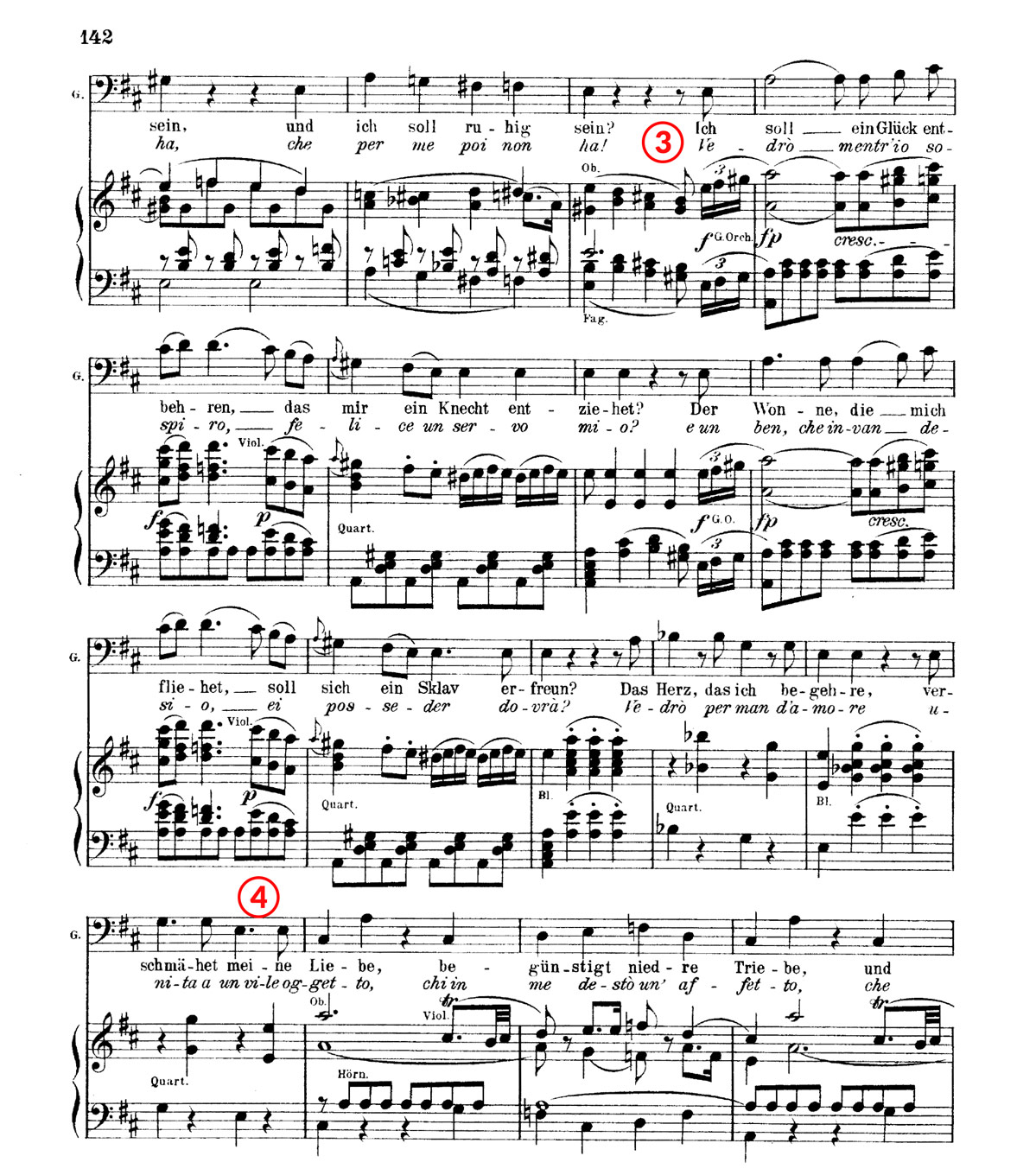

- When the initial aria text comes back, the music underneath it is a bit sunnier than before. Take that as a dramatic cue to help your singing; as you come down from the top of that quick scale up, stay nice and light on “servo mio”. You can keep the rage bit by using the S and rolled R in the word “servo”; make it sound like a swear word, and you’re golden.

- These little rising intervals on “oggetto” and “affetto” are funny; avoid giving them any extra attack. Since the higher notes are on the weaker syllables, it’s an unnatural setting of Italian; but I guarantee they’re not accidental. If there’s something dramatically significant in those “wrong” high notes, make sure we know what it is.

- Getting into the Allegro assai: there are a few ways of setting the new tempo. One way is a conductor setting it for you; if you’re doing it on your own, the best way to be clear is to double the N in “no”. That, plus a rhythmic breath, should be enough information for your orchestra/pianist.

- Each time you get that smeary, snake-like line under “Tu non nascesti,” try and keep the shift from the low F-sharp to the D as smooth as you possibly can. One way to do this is to start the F-sharp with a good amount of sound, and imagine that you’re singing a diminuendo as you go up. There should be no beats, no barlines in this phrase, until you hit those menacing chords under “audace”; it’s an eerie, sociopathic way of setting these words, one of the many sides of an angry Count.

- When you repeat the words, “per ridere”, enjoy that double rolled R (and the funky tritone to the C-sharp). The word “per” can be sung through the teeth, almost, spending most of that quarter note on the R itself. It’ll make sense of the text repetition, and add one more dash his surprise rage.

- Directly after that, the music turns on a dime under “di mia infelicità.” It goes from seething to smug, and I think those couple of bars should be sung as though the Count has already “won the case”. Add a diminuendo, almost a release as the half-note D ties to the next eighth on “mia”; the arpeggio down will be easier to sing because it can be lighter, and the phrase will feel graceful, more noble and highbrow (like the Count himself, of course).

- The laughing can continue through this whole “già la speranza sola” section; keep it light and easy on the voice, and you’ll be in great shape for the triplet coloratura on “e giubilar me fa.”

- I think it’s a nice touch to start the trill on the high C-sharp from the D above as an appoggiatura. It takes a bit of co-ordination, and the trick is leaving breath to properly release the final high D at the end of the word (bonus: you can include the rolled R!).

- Because I know you’re all thinking about that high F-sharp… The music is really exciting by this point, so it’s easy to drive the sound forward, thinking it’ll pay off in high notes. This is one of those places where you can do a lot less; instead of driving forward like the orchestra does, imagine coasting on top of their chords. Your lines are effectively slower than what the orchestra is doing; as a singer, you should take advantage of the time to enjoy making sound. Finally, that last eighth note A before the high F-sharp - you really do have time to sing that with core and spin (but not weight). Of course, you need to plan for the big leap up, but if you concentrate on making healthy sound before it, it’ll be more legato and more reliable.

Questions? Want to request an aria for our Aria Guides? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch at [email protected].

Comments