Aria guides: Va, laisse couler mes larmes

How-ToMassenet’s Werther is a stunner of an opera, based on the stunningly depressing novel by Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther. Charlotte is one of the few who can bring some sunshine into Werther’s world of Sturm und Drang, and though she may reciprocate his feelings for her, she’s married to another man.

Shortly after the famous “Letter Scene,” where she re-reads correspondence between her and Werther, Charlotte sings “Va! laisse couler mes larmes” to Sophie, her younger, more optimistic sister, telling her that it is sometimes a good thing to grieve, and not be consoled.

The aria is compact, dense, and moving, and it’s also a difficult sing. With you teachers and coaches, we can help get you started.

- The a cappella opening to this aria, plus the imperative, “Va!” can add up to an angry start for Charlotte. Though the first phrase has strength, what she says afterwards is comforting, not accusatory. So, using the forte marking, try for an effect that’s not a retort, but instead a release of tension. The tenuto markings over “Va!” and “mes” are about the vowels, so resist the urge to emphasize with the consonants. Massenet is asking you to enjoy the trip on “mes larmes,” and a small portamento between the F and D is effective, and helpful for arriving with a conductor on the downbeat.

- It’s easy for this aria to plod; instead, use the long, long vowels to maintain life and direction in these slow phrases. The syllabic setting, at such a slow tempo, can make it hard for the French to sound natural; as you practice speaking the text, start at speech pace, and then gradually slow it down and lengthen the vowels as needed. One last nice touch for this section: bring out the “ché-” of “chérie!”

- The breath marks that Massenet writes seem to be a bit overkill, and perhaps he’s offering two either/or options instead of saying to take both. A breath before “dans notre” makes a bit more sense than after “âme,” but in an aria like this, you take the breaths you need. The important thing is to keep the sentence moving, and even if you take a breath, the communication isn’t interrupted. There’s a tenuto marking above “-tom-” in “retombent,” but you can also add one on the “re-” to help bring out the rhythm in your low register.

- The three quarter notes at “et de leurs” can feel heavy and trudging, so make sure that you start this phrase in a way that sets you up well for its upwards line. The breath you take before “martèlent” needs to be a good one, and you have more time than you think to take it; don’t feel rushed to stay with the orchestra. When you get up on the repeated F-naturals, practice them as a sustained half-note F, rather than getting too used to the syllabic breaks for the text. Lastly, that’s a real Massenet portamento at the end of the line, connecting “et las” (continued below). Stay on your “et” vowel, and enjoy the opportunity to word-paint for “las,” or “weary.”

- More portamenti here, plus a bit of a faster tempo; the bars here should have a feeling of a slow, swinging 2. The portamenti shouldn’t let the tempo drag, but instead they’re a gesture of sighing. Get picky with the intonation of the first A-natural in “résistance” and the first F-sharp in “s’épuise,” and be sure those notes are vibrating.

- This is probably the most speech-like line in this aria. You can enjoy the [k] sounds in “coeur” and “creuse,” and balance them out with long vowels. Spend time tracking the crescendo and diminuendo, deciding where to start growing, where to peak, and how soft you want to get by the end of “s’affaiblit.” It may seem like over-thinking it, but it can be harder than you think to pace something simple like dynamics at such a slow tempo.

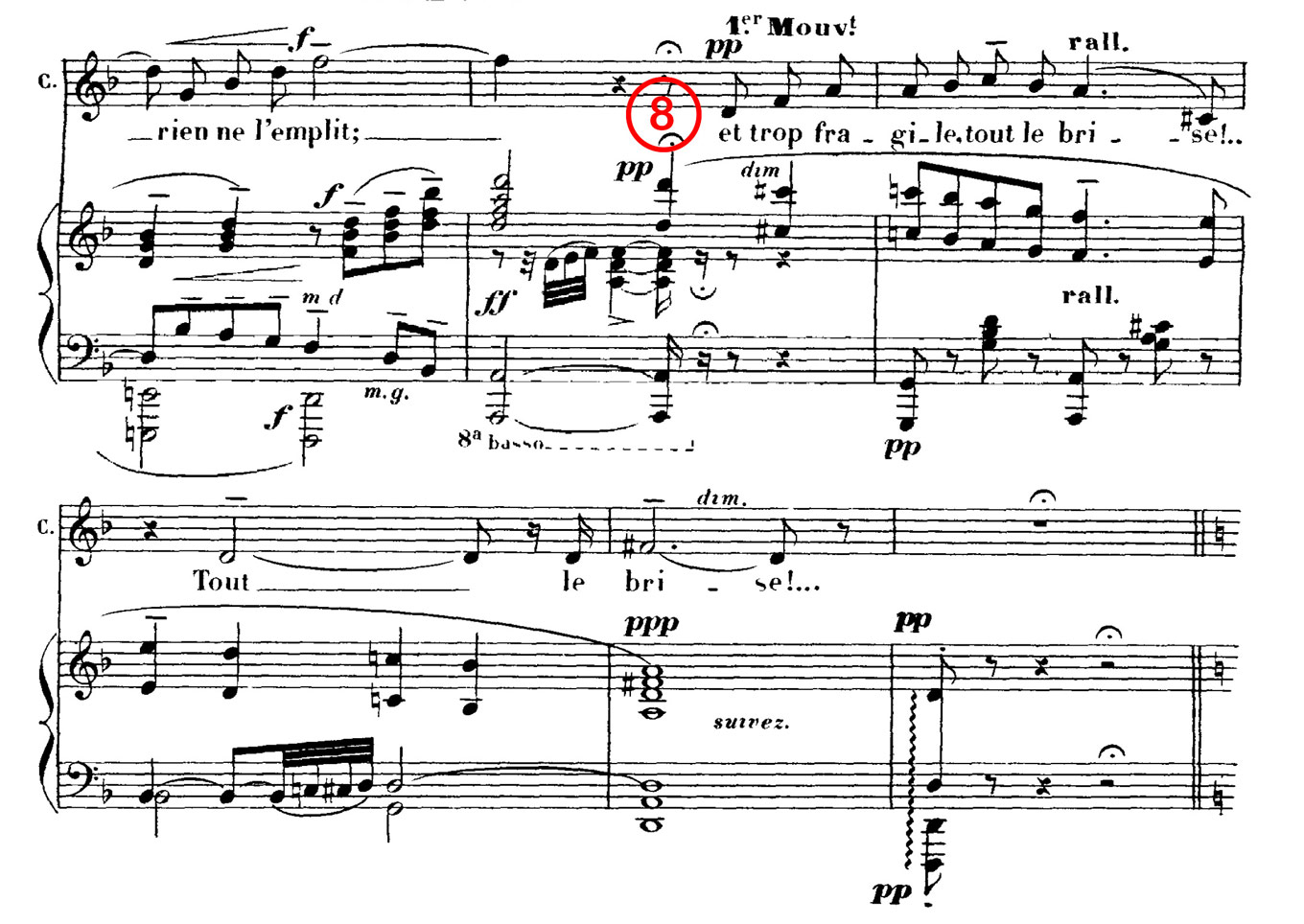

- It looks like nothing special on the page, but these bars of “il et trop grand, rien ne l’emplit” (below) make up the real peak moment in the aria. Be picky with intonantion as you rise up by thirds. Make sure that you’re singing a vibrating vowel on “trop,” and on the first syllable of “l’emplit,” so the high notes of each gesture aren’t isolated, but really seem to grow out of the whole bar. Assuming you’ve got the air to do it, make sure you don’t cut off too soon at “l’emplit.”

- Wait for all the orchestra rumblings to clear away, leaving just the sustained D’s in the winds. Take that pianissimo marking with a grain of salt; the loudness in the previous bar, plus the change in register, will already give dynamic contrast. Enjoy the tenutos over “tout,” and pace the portamento in “brise” so that you don’t start to descend too soon.

Comments