Discomfort: Louis Riel at the COC

Review“Louder, please,” barked the inconsiderate, entitled man sitting in an upper ring of the Four Seasons Centre, as Cole Alvis (The Activist) welcomed the audience to the Canadian Opera Company’s new production of Harry Somers’ Louis Riel.

The interruption seemed to set the tone for the opera, written in 1967 for Canada’s centennial, which tells the story of the Métis leader who founded the province of Manitoba, and led two resistance movements against prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald. The story is one of racism and xenophobia, cloaked transparently in the guise of establishing - or preserving, as the case may be - a “great” country.

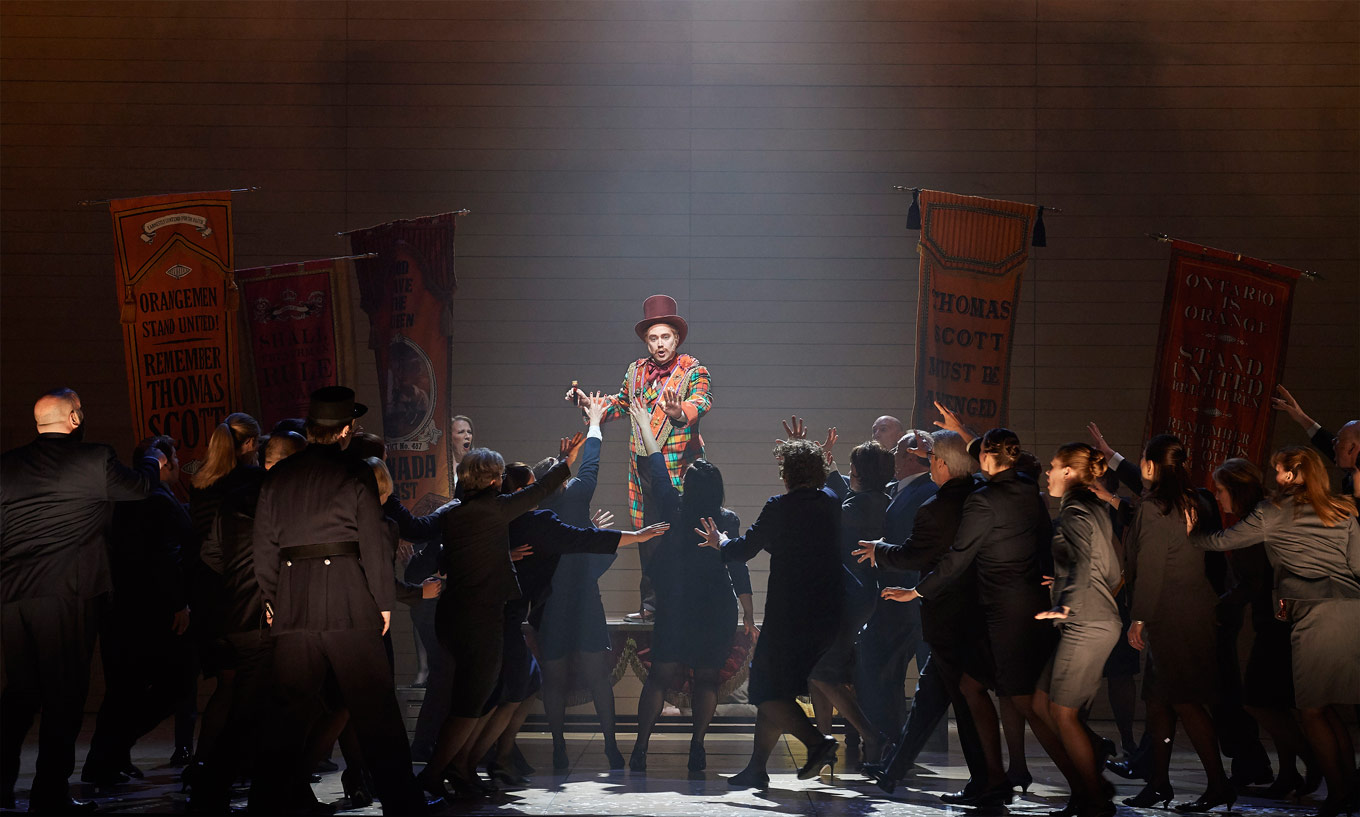

Louis Riel is an uncomfortable opera. The score assaults the ear with dissonance and cacophonous noise, and Somers seems to press the singers right up against the boundary between vocal expression and vocal abuse. The hate from both sides of Canada is founded in ignorance and fear, and the real-life-inspired characters seem to embolden their own national pride with their loathing for the “other”. Even in 2017, Canada’s neighbour is a country with a government which preys on the same kind of stupid, ignorance-fueled racism that existed in the 19th century; for white, anglophone Canadians, Louis Riel should be a reminder that our own country’s history comes with similar shame.

Even seasoned operagoers will find themselves heavily laden with the story of Louis Riel, the music of Harry Somers, and the opera’s new production by Peter Hinton. Where does one begin to talk about it? To say you “liked” it is sort of like saying you “liked” An Inconvenient Truth or you “liked” the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin. Louis Riel offers no toe-tapping tunes, and few characters who are entirely unpacked; it’s an honest approach by Somers and librettists Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand, to tell this story through a series of keyholes which allow us to see what a character does or says, but perhaps not entirely why.

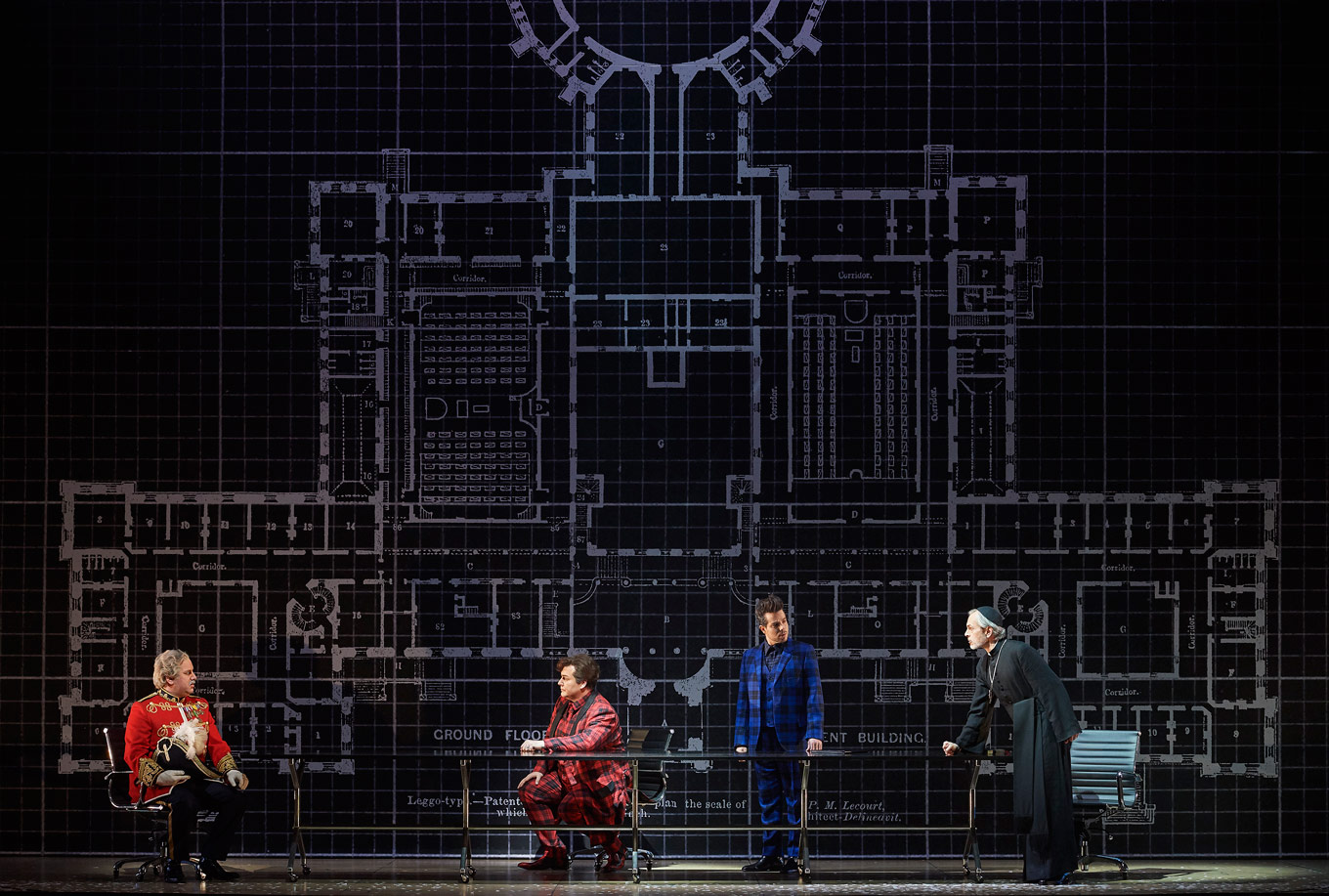

With an enormous cast and a complicated score, it’s an impressive feat to present Louis Riel at all. Hinton’s production introduces the conveyor belt of new characters with great specificity; Dr. Schultz the opportunist, Donald Smith the businessman, and Bishop Taché the manipulated were made crystal clear with precious little stage time. Gillian Gallow’s ingenious costumes and Michael Gianfrancesco’s looming sets seemed to keep the story and its characters in every time period, reminding us of what was, and what still is.

Louis Riel - sung desperately by Russell Braun - is a large figure who seemed to take up too much space. James Westman is a beautifully exaggerated figure in Riel’s adversary, Sir John A. Macdonald; almost laughably so, the Prime Minister shows himself a man whose world is surprisingly small, considering the vast country he runs. Though there is more justice in Riel’s cause, both leaders come with flaws, and they both make decisions that are impossible, despite a “right” answer’s being clear to the outsider.

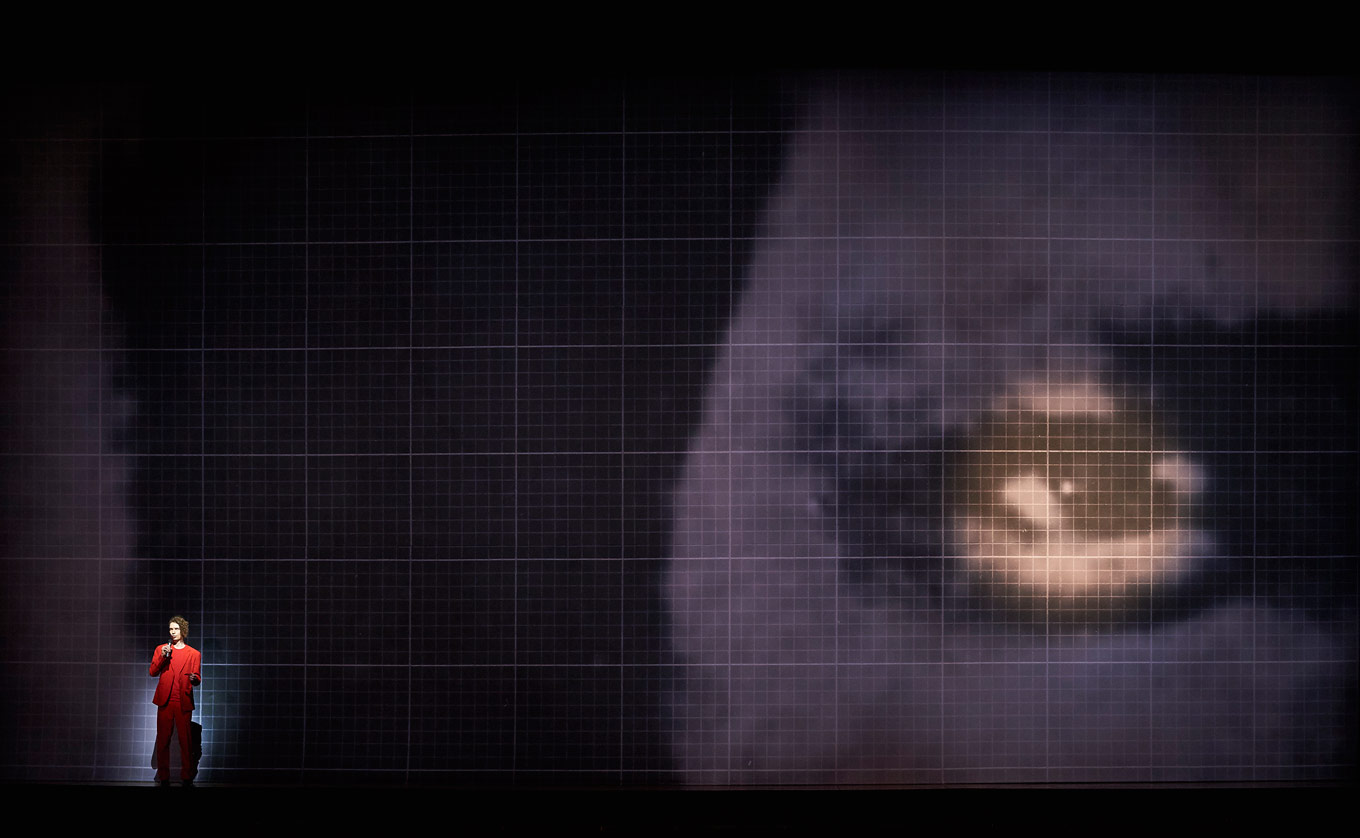

The cast of Canadians is strong, and each artist seems to approach their role with a certain deference, acutely aware of the public eye that is focused on this new production in Canada’s 150th year. To the large cast and chorus, Peter Hinton adds a “silent chorus” of sorts, a group of non-speaking, non-singing Métis and indigenous performers, contemporarily dressed in red, and later in black. “They are in all of the action, they frame the action, they resist the action, and they are affected by everything that happens, but they are silent,” Hinton told Michael Cooper of The New York Times

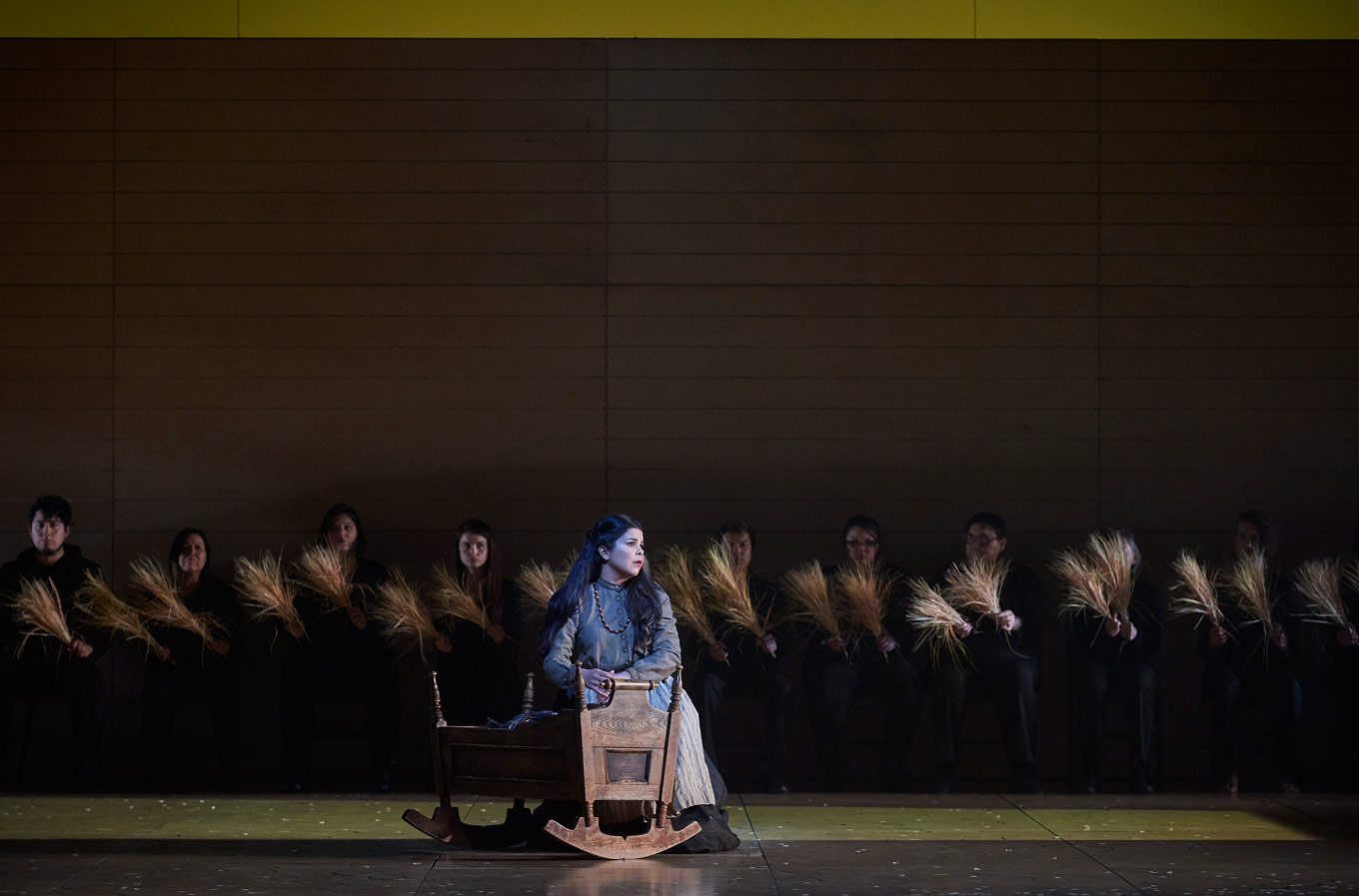

It’s perhaps a retroactive bandaid-like response to the fact that, among the many people onstage, shockingly few of the vocal performers are of First Nations descent. A late fix though it may be, Hinton’s silent chorus is a thoughtful addition to Louis Riel, one that marks the societal changes between 1967 and today. These silent performers are a strong visual presence throughout the production, and so it draws the eye when their movements and choreography are less than uniform. There was a disappointing moment, during Marguerite Riel’s moving lullaby (sung powerfully by Simone Osborne), when two members of the silent chorus stuck out like sore thumbs, their movements full of bored insolence while having a visible conversation amongs themselves.

Perhaps without Hinton’s supernumeraries, Louis Riel might have been more “comfortable” for Toronto audiences. With the faces of the affected placed right amid a piece of theatre that comes out of a Western European tradition, the production seems to mirror the slow, significant steps being taken by Canada as a whole, beginning with the acknowledgement of injustice within our country’s short history.

Maybe it’s a function of Somers’ opera that the story and its affect still seem muddled in my head. Is Louis Riel more “objective” than our history books? Is discomfort a good first step towards honesty and reparations? Am I, a white anglophone Canadian, like those Ontarians of the 19th century?

Louis Riel runs at the Four Seasons Centre until May 13. For details, and to purchase tickets, click here. For more production images, click on our gallery below.

Comments