In review: Lulu at ENO

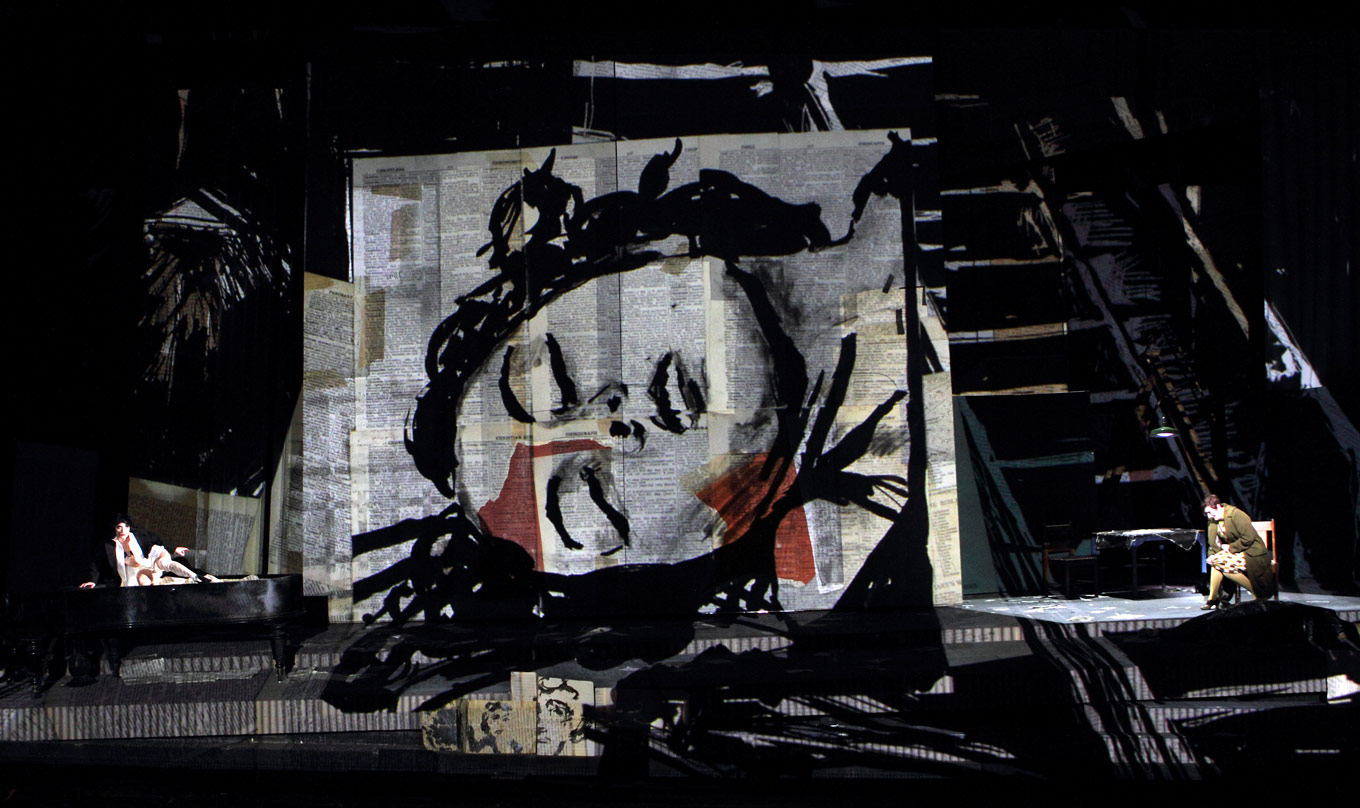

ReviewWilliam Kentridge’s production of Berg’s Lulu has made it to English National Opera, after critically-acclaimed runs in Amsterdam and New York. With his co-director Luc de Wit, and designers Sabine Theunissen, Greta Goiris, Urs Schönebaum, and Catherine Meyburgh, Kentridge’s own ink sketches are the inspiration behind the fractured look of this story; he sets Lulu in the late 1920s/early 1930s, the look of newspapers and cabaret theatre splitting the stage between the action and a reference to the art of it all.

Soprano Brenda Rae makes an extraordinary role and house debut as Lulu. It’s a feat simply to learn and sing the role, and Rae seemed to find ease in the quick turns from blazing coloratura to sustaining high, soaring lines. Her voice has a softness about it that seemed to bring out the subtle, muted danger in the title character; when she showed off more vocal extremes, we understood Lulu’s volatility and unpredictability. Rae seemed constantly comfortable onstage, in her stages of undress and tough musical demands; she made sense of Berg’s dense writing, as if Lulu’s music were simply the exaggerated, unnerving way that she speaks.

James Morris seemed a perfect Dr. Schön, as if he represented that paternal, rational (mostly) figure that most of us know in our own lives. The notorious point and immediacy in his sound kept his scenes quite conversational; upon his return as Jack the Ripper, that almost-casual quality gave a nod to the inevitability of Lulu’s fate. Sarah Connolly was an earnest, heart-breaking Countess Geschwitz; the beauty in her sound made us mourn for her, for what she sacrifices for the likes of Lulu.

Among the beautifully-casted ensemble were a few more highlights. Nicky Spence’s Alwa, Michael Colvin’s Painter, and David Soar as the Animal Tamer/Athlete were all gracious doses of sanity. Sarah Labiner as the Fifteen-Year-Old Girl was boyish and energetic, and her scenes conjured up memories of Cherubino and his infatuation with Rosina. Wisely sung and fully human, these were the characters that inspire the question: why do these people put up with Lulu?

Kentridge kept reminding us, with sloppy/minimalist sketches of breasts and bushes, that it was Lulu’s looks and sexuality that maintained her entourage, revolving-door-like as it may be. Yet the production never vilified Lulu; instead of someone who simply sleeps her way to the top, Kentridge’s Lulu is a woman convinced that her only power lies between her legs - and when surrounded by men who whinge about what year she was the hottest, who can blame her for wielding said power?

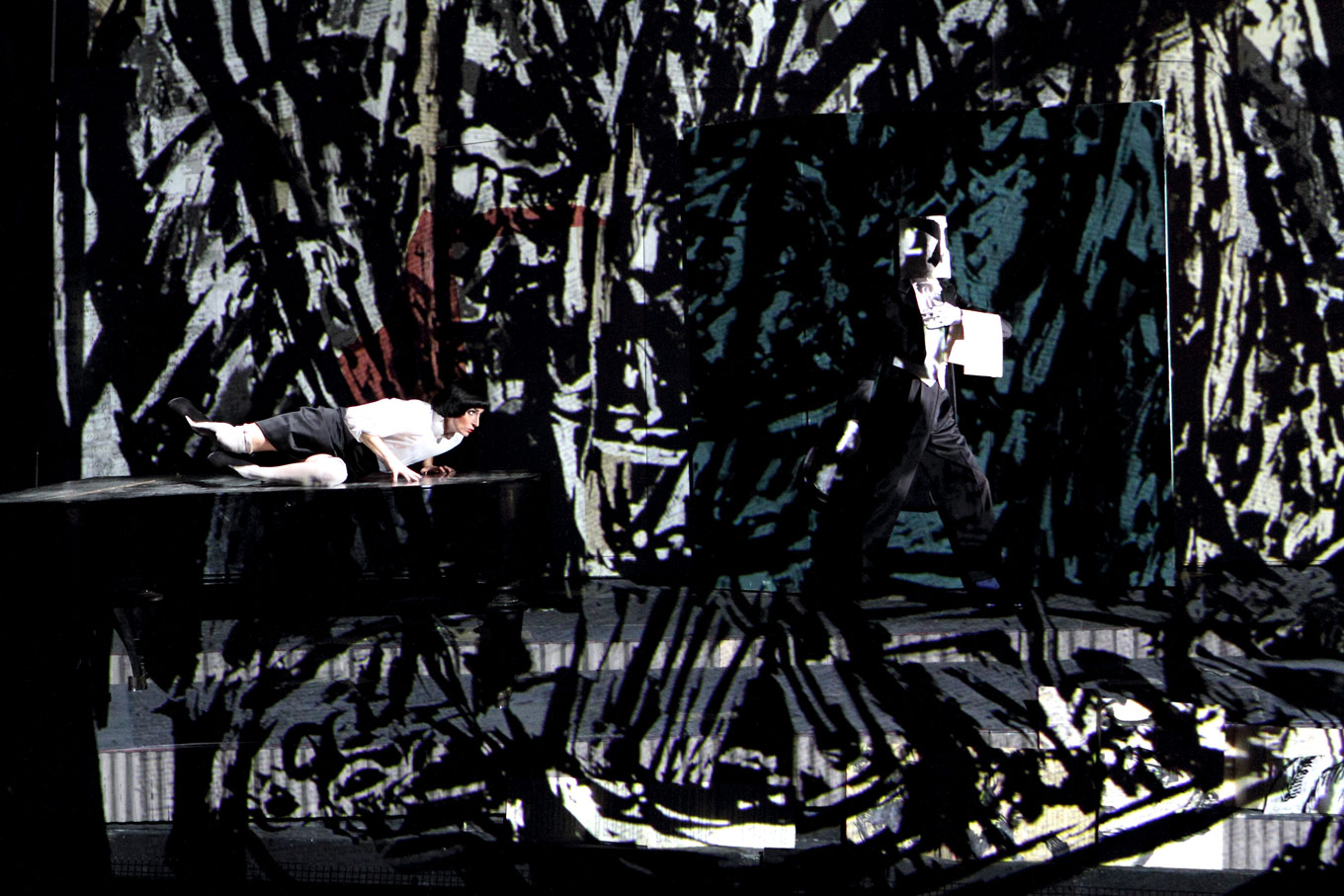

Two solo performers - Joanna Dudley and Andrea Fabi - lived in the bizarre, surreal world around Lulu’s story, and they seemed to align themselves with the characters onstage. They were butlers with odd physicality, or pianists who anthropomorphize Berg’s sheet music; most importantly, they acted both as agents to Lulu’s demise (by passing the blade to Jack the Ripper), and as her fierce protectors, coiled and ready to pounce on those who would hurt her.

We have our own exasperations with the idea of a femme fatale, especially when they’re two-dimensional, relying predictably on sex and spineless men. Yet Kentridge’s Lulu brings us into a specific world, while seeming to simply reveal the story without bias. Like Berg’s score, the production is one we’re eager to see again, to notice more details in Kentridge’s layered work.

Lulu runs at ENO until November 19. For details and tickets, click here.

Comments