Jacqueline: Come for the music, stay for everything else

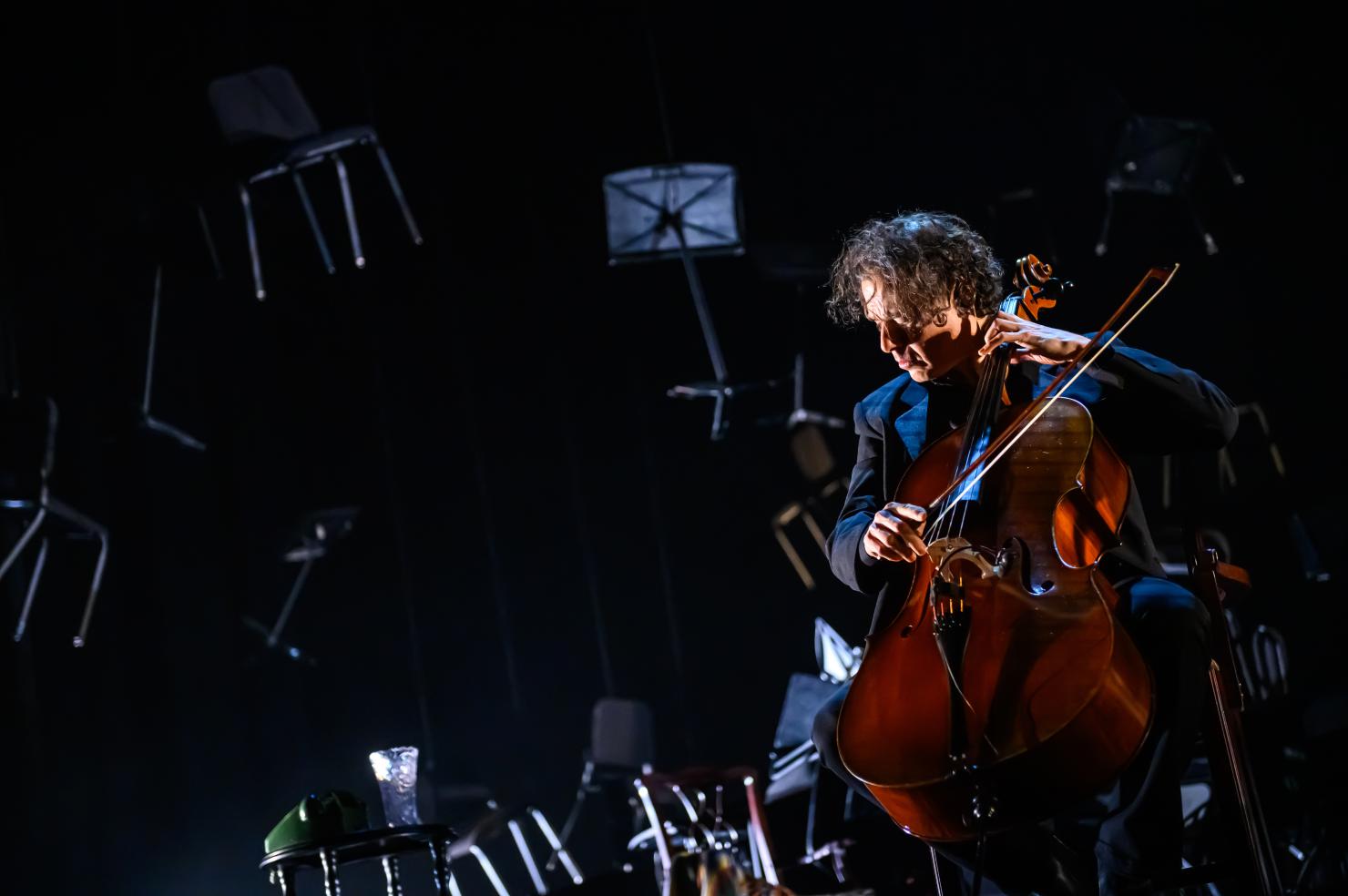

ReviewTapestry Opera continues their 40th anniversary season with Jacqueline, a commission for Canadian librettist Royce Vavrek and American composer Luna Pearl Woolf; the end result, directed by Tapestry Artistic Director Michael Mori, is something of a living retrospective of the life and times—and plight—of seminal cellist Jacquelin du Pré. A living retrospective because one-half of the two-person show is cellist Matt Haimovitz, who in his teens enjoyed a relationship with an ailing du Pré, at the invitation of her husband and music partner Daniel Barenboim. His presence on stage and behind his instrument added a silent narrative to the work, adding equal parts gravitas and relatability. There’s an ambiguous line of separation between his performance from the fact of the personal memories he was sharing through music.

That ambiguity, however, does a net good because of the attention commanded by soprano Marnie Breckenridge’s performance. So dominant is her stage presence that the work at times felt like a one-woman show, with Haimovitz’s accompaniment being a source of contrast and depth. Likewise, there is so much music for the cello part that it at times felt like a three-person show, if you count the cello.

It is a laborious instrument, requiring full-body composure and, among particularly expressive cellists, is seemingly fretted by dramatic eyebrow scrunching.

In a biopic about his childhood in Liverpool, British director Terence Davies relied entirely on music, going as far as saying that “in memory everything happens to music”, in that sense does one expect an embarrassment of riches when those memories are of the life of a musician—and Woolf makes the most of this special case. Jacqueline is a concatenation of memories, and despite Breckenridge’s precision in evocative dramatization, and the eye-level surtitles to dispel the spectre of misheard lyrics, it’s nevertheless difficult to locate the age and corresponding psyche of her Jacqueline throughout. The only clear divides are between health and sickness, her samsonian vigour and the disconsolation at the onset of the usual symptoms of her Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis. The music, however, is a constant, evocative of a mature and brazen Jacqueline, the cradle of the seriousness and depth of her feeling that the libretto at times fumbles. As far as expressing the spectrum of du Pré’s obsession with her instrument—from an adolescent enchanted by its contours to a woman confident no one would ever play it as well as her—Vavrek could not have written a better part for Breckenridge’s more than convincing delivery.

Du Pré was diagnosed with MS at the age of 26, and succumbed to it at 42. That’s 16 years of the slow-burning disintegration of her physical and psychological constitution, almost as long as all she’s known of health and the promises of her solar career. Fitting that incomprehensible contrast into the span of ninety minutes is the challenge Vavrek’s libretto rises to, though it at times rings like the echo chambers of one of Sylvia Plath’s confessionals. But when it works, it works because of the vividity of its metaphors and its reluctance to be swept up in either rage, despair, or a lukewarm self-pity. This portrait is that of several Jacquelines all vying to be remembered: a talented cellist, a devout wife, an amateur comedian, and a avid subscriber to the power of music and vinyl records.

The opera provides two alternative voices to reveal the complexities of du Pré’s personhood; music written for the voice in a way reveals her public personality, along with hear-say gathered from relationships and journals, while music written for the cello presents a quieter inner voice, the private room of her spiritual thoughts. To that end, Breckenridge delivers a virtuosic performance, landing the occasionally hair-raising note. Haimovitz’s performance is similarly virtuosic, playing intermittently as accompaniment for voice as well as in direct dialogue with Breckenridge.

In a sense his cello, known as a “tenor” instrument, provides a counterpart to Brekenridge’s soprano for a robust operatic experience. And for that reason do I think the use of audio recordings in addition to Haimovitz’s performance takes away more than it adds, interrupting the sense of here-ness and presence the show enjoyed for the majority of it’s duration—especially when the contrast between the richness cello’s sound quality and that of the recording is fairly obvious.

This is a production that knows how to make a lot out of a little.

This work is also a celebration of the instrument, as much as spotlight as the cello can get for nearly ninety minutes of non-stop playing—praise be to Woolf for letting the music evolve and maneuver as much as the libretto. It also provides a bit of insurance, for the sake of those who are only peripherally familiar with the life and times of du Pré, one learns of her here through the unique obsession cellists can have with their instrument. We live now in a new generation of international cellists like Sheku Kanneh-Mason (who is the new face of the Elgar Cello Concerto that launched du Pré), French star Camille Thomas and precocious Instagram proteges like @cellodude06—the instrument has found another round of devotees at a world class level, all similarly enticed by the full-body embrace of its lacquered torso. It is a laborious instrument, requiring full-body composure and, among particularly expressive cellists, is seemingly fretted by dramatic eyebrow scrunching. What is unique of its sound is the range of its expression, and Woolf utilizes the fullness of this spectrum to keep pace and accentuate everything happening for voice, evoking Jacqueline’s disconsolation with a steady supply of craggy figuration.

The libretto does a good job of keeping the work personal, not venturing too far into the metaphorization of her illness, save for an oddly placed but well landed joke about teenage monks forced to watch exotic dancing as a final test of their asceticism. Then there’s the recurring motif of Samson from the bible, “For I am Samson, heady, hale and invincible,” a reference to du Pré’s famous blonde mane, as well as the strength she feels at the command of her instrument. A clever metaphorical instrument, but I feel an opportunity was missed here to find a female version of Samson, real or fictional, to make the point.

The set (designed by Camellia Koo) is fairly unimaginative, but it does a great job of evoking a sense of variety while using many of the same props—a clever solution to filling the Betty Oliphant Theatre stage with just two bodies. The lighting design (Bonnie Beecher) too contributes significantly to the intimacy that the show never lost, keeping our attention in the fore-most front of the stage while maintaining a sense of depth with the dynamic pieces of the set in the background. All in all, this is a production that knows how to make a lot out of a little, a feat owed to Breckenridge’s prowess and Haimovitz’s facility; and, crucially, it never loses its focus on the centrality of the music.

So yes: go for the music, stay for everything else.

Comments