La Nilsson: celebrating Birgit Nilsson at 100

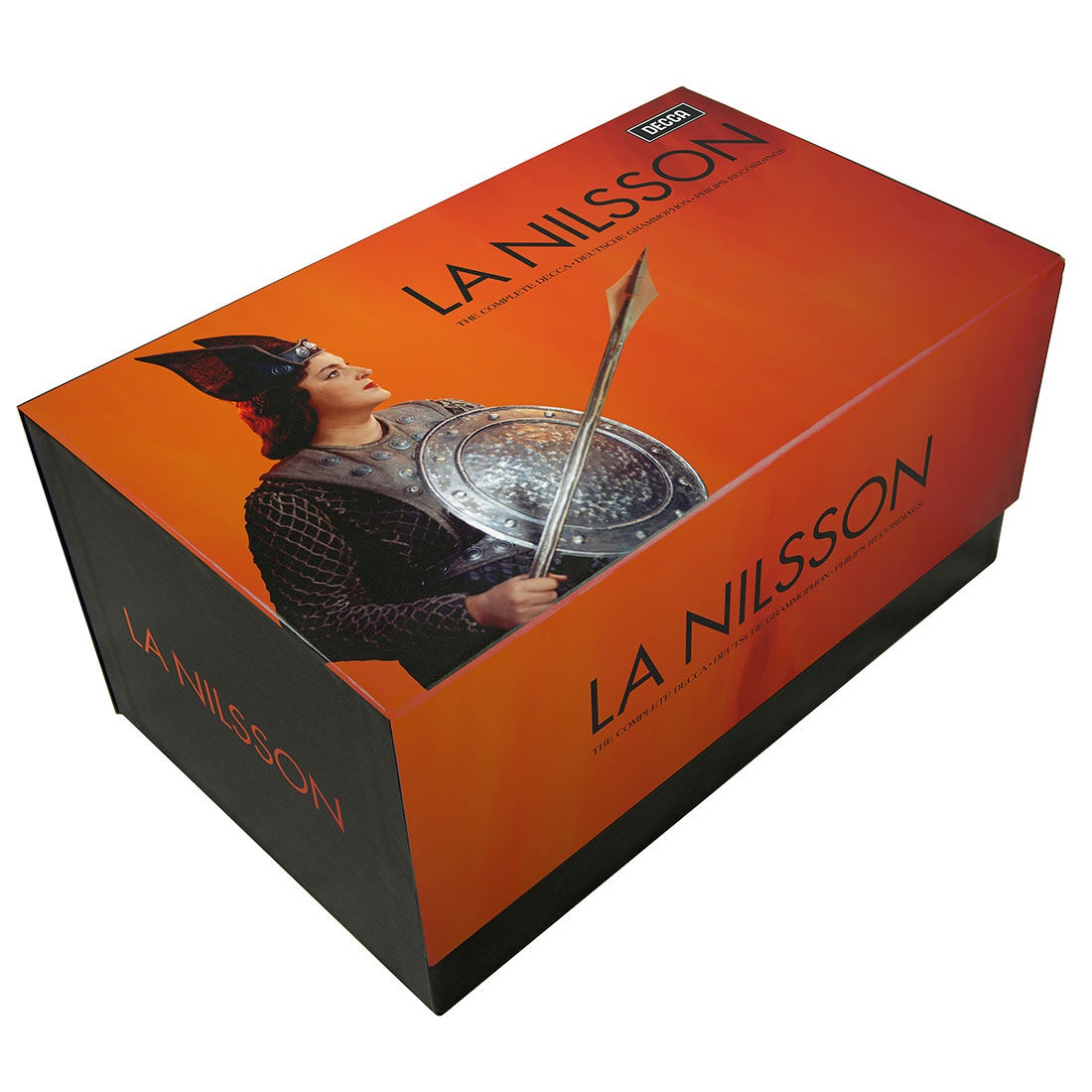

Op-EdThe box seems to generate its own energy. Covered in sophisticated hues of copper and gray with a resplendent image of Birgit Nilsson as Brünnhilde, who had surely passed through hair and make-up before leaving Valhalla, it is of monolithic proportions. The subtle click of padded magnets on the front gives the impression of substance and staying power, in short the essence of Nilsson.

This boxed set of newly remastered studio recordings, primarily on Decca, Deutsche Grammophon, and Philips, celebrates the 100th anniversary of her birth that took place on May 17, 1918. This is not so much a review as it is a consideration of greatness and how effectively it can be repackaged.

Few, if any, opera singers have achieved the consistent critical acclaim and public adoration, as has Nilsson. Her flawless technique and boundless energy are spectacularly represented on 81 disks, including 79 compact disks and two DVDs. Additionally a formidable book tops the package containing complete track listings and illuminating essays - along with a few errors that will send fans scurrying off to confirm the facts. The book is generously graced with performance and rehearsal photographs. There is also an abundance of candid shots that capture Nilsson’s vibrant personality. Together they portray Nilsson in all manner or action whether riding the hell out of an exercise bike during the 1966 Elektra recording or as a rather formally posed Minnie, with gun on hip from Puccini’s La fanciulla del West.

We’ve known this Ring for decades. It was the first ever recording of the cycle in a studio, a pioneer in stereophonic technology, and the signature work of Decca producer, John Culshaw.

At the least this luxurious but not excessively packaged collection - let’s call it Brünnhildian - offers the opportunity to worship this peerless operatic goddess from a single source. For those who are coming to know Nilsson only now, it is quite simply a treasure trove.

But where does one start? Channeling the mischievous spirit that has long been associated with Nilsson, I resisted the obvious lure of the Ring and opted for Tosca. Yes, La Nilsson travels beyond Wagner and Strauss to include Puccini, Verdi, Mozart, Beethoven, Sibelius and Weber as well.

Franco Corelli and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau join Nilsson in this Tosca that has by some been termed a veritable shouting match. With a sexually harassed Tosca, a tortured Cavaradossi, and a sadistic Scarpia, there is plenty of reason to shout. The result however is three pitch-perfect singers who go for intensity and volume over characterization. Despite this wacky approach, the recording gels in its own unorthodox manner because the powerhouse singers are matched by the ferocious intensity with which Lorin Maazel propels the orchestra of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia. If nothing else, it’s an ear-opener.

Mischief satisfied, I succumbed to the Ring and found myself in Vienna’s Sofiensaal, that legendary dancehall turned Decca recording studio, for Sir Georg Solti’s historic studio recording. We’ve known this Ring for decades. It was the first ever recording of the cycle in a studio, a pioneer in stereophonic technology, and the signature work of Decca producer, John Culshaw. Listening to this Ring and subsequent recordings for which Culshaw served as producer, it becomes apparent that he exerted a significant influence on Nilsson’s studio recording oeuvre.

The Golden Ring, one of the two DVDs included, while mainly centered on the recording of Götterdämmerung, tells of how Culshaw convinced Decca executives that a studio Ring Cycle was economically viable when he persuaded the legendary Kirsten Flagstad to sing the relatively small role of Fricka. Sadly, Flagstad’s failing health allowed her to assume the role only on Das Rheingold. The great Christa Ludwig stepped in for Die Walküre.

This film, regarded as one of the best musical documentaries every made, provides some indication of Culshaw’s interpersonal acumen in dealing both with Nilsson who had definite ideas about her vocal placement and with a rather highly-strung Solti. While listening anew to this Ring one might go for immersion status by reading Culshaw’s captivating Ring Resounding, his memoir that chronicles life at the Sofiensaal during the seven-year recording process. It’s the ultimate insider’s view of a rare artistic and technological collaboration. It is also quite funny, opinionated, and full of surprises.

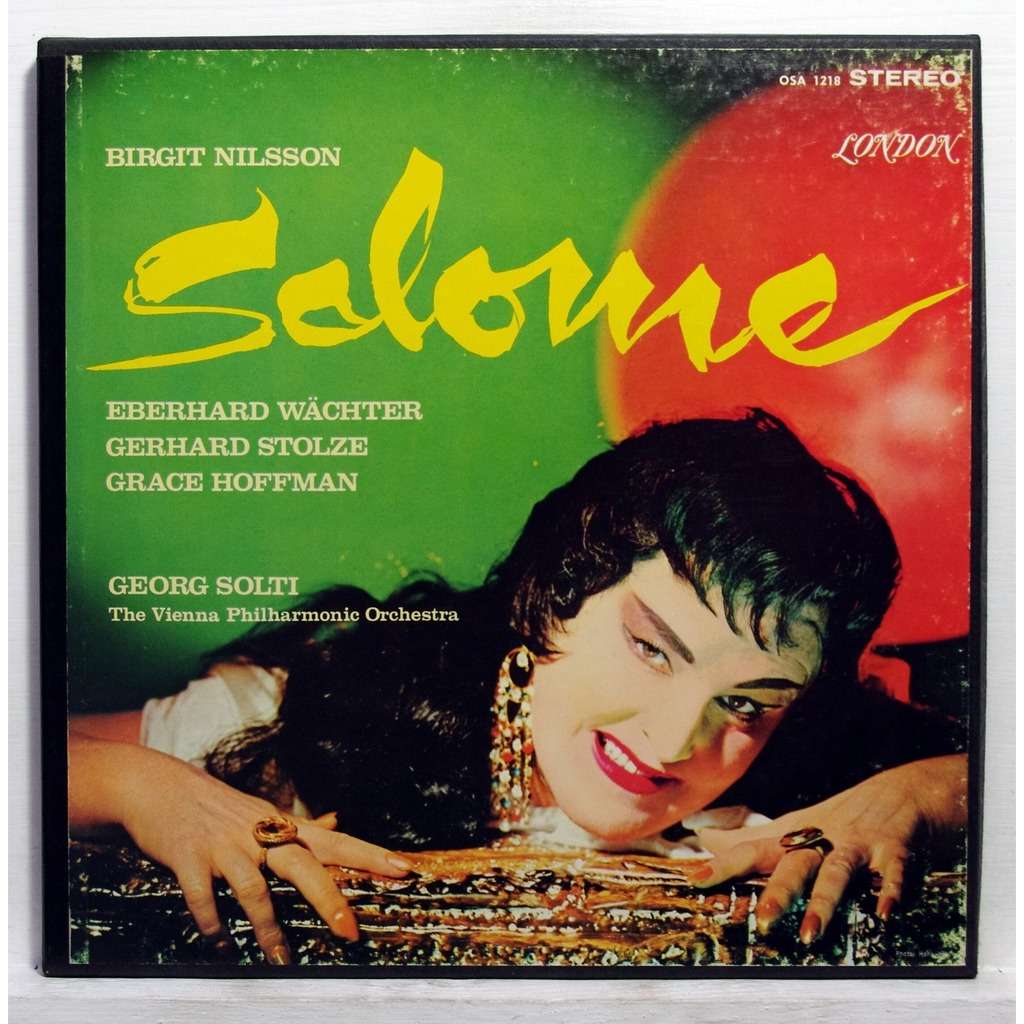

The exotically clad Nilsson looked more like the cat who swallowed the canary than the disturbed teen-age princess who had violated the severed head of John the Baptist.

An attendant luxury of La Nilsson is the inclusion of still another Ring, this one from Wagner’s own stage at Bayreuth and under the more relaxed baton of Karl Böhm. Within easy proximity we can hear how Nilsson’s Brünnhilde adapts to each environment, most especially in her Walküre Act III exchanges with the Wotans of Theo Adam on stage and George London in the studio. Clearly this additional Ring is included not to encourage listeners to judge one over the other but to experience the voice, technique and interpretative prowess of Nilsson from a broad perspective. It would be folly to deny the pleasure and Wagnerian insight that La Nilsson offers by deeming one superior to the other. This is a centennial birthday celebration after all, not a debate over a foregone conclusion.

One has a similar if less complex reaction to the two recordings of Turandot included, both with the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. The first, recorded in 1959 under Erich Leinsdorf, and borrowed for the collection from RCA, has the distinction of possessing Jussi Björling as Calaf and Renata Tabaldi as Liù. In the 1965 recording under Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, Nilsson is joined by Franco Corelli and Renata Scotto. When it comes to Nilsson, we know that her interpretation will revolve around an arch and uncompromising princess that was the Turandot of her era. Recently Nina Stemme, who is in the process of becoming Nilsson’s heir apparent, has done much to humanize this character. While Corelli is ardent, Björling is transcendent and listeners can compare the remastered Renatas with all of the scrutiny they care to apply. Perhaps this is La Nilsson’s contribution to rainy day fun.

Richard Strauss’ two one-act operas, Salome and Elektra, both recorded at the Sofiensaal under Solti and produced by Culshaw, retain pride of place. They may constitute Nilsson’s greatest hold on recorded immorality. Along with the composer’s Die Frau ohne Schatten with Böhm, recorded live at the Vienna State Opera, they remain definitive recordings despite what some consider excessive studio intervention on Salome.

Elektra retains a dramatic standard that has yet to be equaled. Here it assumes the role of a companion piece to the 1980 video from the Metropolitan Opera under James Levine. Leonie Rysanek as Chrysothemis joins Nilsson in a production that looks a bit frumpy by today’s standards but is nonetheless a potent reminder of two powerful singing actresses. Additionally Mignon Dunn revels in Klytaemnestra’s guilt and mines every bit of the role’s gallows humor.

The cover photo for Salome, having survived several packaging concepts over the years, continues to fascinate. When I first saw it on a boxed set of LPs in a sidewalk stand outside a liquor store, the exotically clad Nilsson looked more like the cat who swallowed the canary than the disturbed teen-age princess who had violated the severed head of John the Baptist. Surely Decca’s designers weren’t being flip during the photo session so perhaps Nilsson was up to some subtle mischief that has managed to last for decades. Nilsson was well known for her practical jokes and a humorous thread runs subtly through many of the photos in the accompanying book and reproduced LP covers.

Stemme, by the way, was awarded the 2018 Birgit Nilsson Prize; a $1 million gift awarded every three years by the Birgit Nilsson Foundation, for artistic excellence that will stand the test of time. She has stepped with rare distinction into Nilsson territory with acclaimed interpretations of Elektra, Isolde and Salome in addition to Turandot. While on the subject of money, Nilsson appears as a benignly rendered Elektra on the 500 Kronor Swedish bank note. She joins the likes of Ingmar Bergman and Greta Garbo to put this recognition in cultural perspective.

In addition to cooperating with La Nilsson, the foundation authorized the release of a set of live Nilsson recordings featuring Die Walküre at the Metropolitan Opera under Herbert von Karajan, two Tristans, two Elektras and a Turandot conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Those inclined to listen for vocal strain in these live recordings will have their work cut out for them.

Many collections of the size and scope of La Nilsson have their catchall disk, where this and that, as it were, takes up residence. Here that role falls to the lovely collection of Scandinavian songs, Land of the Midnight Sun. With plenty of room left on the CD transfer, the space is filled by the Christmas standards, “O Holy Night”, “Ava Maria” (Gounod), “Panis Angelicus” and “Silent Night”. As if to give Culshaw the last word, the CD ends with “I Could Have Danced All Night”, from Lerner and Loewe’s My Fair Lady, in which Nilsson belts the last note into the heavens. Her show-stopping rendition appeared in a faux gala that Culshaw concocted for a recording of Die Fledermaus including such opera greats as Leontyne Price, Joan Sutherland and Jussi Björling. While it does nothing to unite the disk it is a witty and dazzling moment.

Who but Nilsson has captured with such refined exuberance and reverence Elizabeth’s aria from Tannhäuser, “Dich, teure Halle”?

La Nilsson’s first three disks, the obvious entry point, capture the 1960 Tristan and Isolde with Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic followed by a rehearsal session narrated by Culshaw, a sober introduction to the collection for sure. Were I to search for an entry point once again, I might forego the obvious, also resist the temptation of Tosca (disks 37 and 38) and move one up to 39, the collection of arias by Wagner, Weber, and Beethoven. Who but Nilsson has captured with such refined exuberance and reverence Elizabeth’s aria from Tannhäuser, “Dich, teure Halle”? By any measure, this is La Nilsson’s welcome of welcomes, one that captures Nilsson’s superb artistry and, when taken out of strict operatic context, a hint of her mischievous nature as well.

Comments