Living up to its name: Experiments in Opera

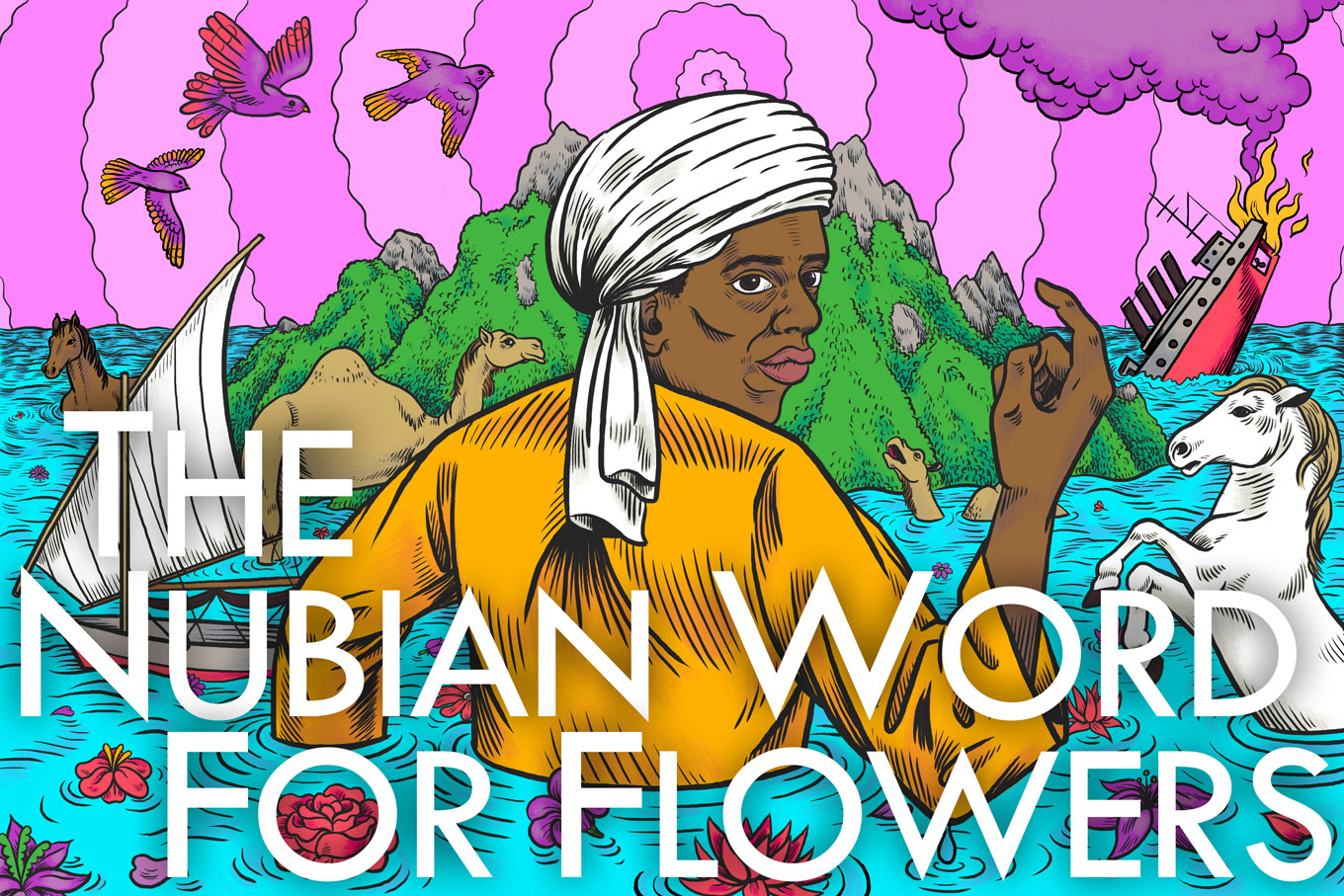

InterviewSince 2010, New York-based Experiments in Opera has set about “re-writing the story of opera.” They are a composer-run organization that fosters new works, and treats the genre of opera as something that can tell fun, engaging stories that challenge what it means to be relevant and experimental. Their current upcoming project is The Nubian Word for Flowers, by Pauline Oliveros and IONE; with EiO and the International Contemporary Ensemble, IONE honours Oliveros’ legacy with the opera’s posthumous completion and world premiere.

We chatted with co-founders Aaron Siegel, Matthew Welch, and Jason Cady, about new opera, the composer’s perspective on the workshop process, and how they define a “successful” opera.

How is EiO’s mission unique, compared to other organizations that foster new works?

Aaron: Since EiO is run by composers, we are interested in creating challenges for other composers that make them think more deeply about what opera is and can be. We generally don’t get excited about opera pitches that come from composers who have written a piece and just want us to pay for it to be produced. Our most successful projects are ones where we invite composers to make work in a community where everyone is being asked to respond to similar restraints of story, instrumentation, performers, etc. This way, we can create an artistic dialogue about the process, invite audiences to note the differences between each composers’ styles and approaches, and engage a wider and more diverse range of singers and instrumentalists who are flexible in terms of style, genre and technique.

In this way, we are as much a commissioning organization as we are a producing organization. Each of the works we produce is commissioned in some way or another. It’s not just part of what we do, it’s ALL of what we do!

When it comes to creating new opera, what about the composer’s process might the average person not realize?

Jason: I usually start with a premise for a story or scene and everything else (instrumentation, form, etc.) follows from the narrative.

Aaron: I am always struck by how difficult it is to shut out all of the historical precedents when creating new art. It’s great to know your history and whose work you are benefitting from stylistically, etc., but when it comes time to create new work, it’s important to let all of those ideas fall away. While making new opera, that means letting go of the scale and form of traditional opera. Just because Verdi or even Philip Glass uses a chorus in their operas, that doesn’t mean that I have to use a chorus. Just because most operas use a recit/aria structure doesn’t mean that I have to do that. Part of the composers’ process is resisting all of the precedents, and reaching for new models of working. Most people don’t usually think about the creative process being about resistance, but it is a big part of creating work that has a unique identity.

Matt: I think it is underrepresented how much control the composer has over the libretto — they can be involved heavily in the libretto. Often some of the most organic text setting comes from words written or rephrased by the composer. The mythical idea of the libretto as some handed-down “sacred” text that the composer is slave to can be dismissed. Choosing who to collaborate with on the text is crucial, and ideally the work is fully generated in collaboration to best serve the expressiveness and clarity of the interdisciplinary elements so that they fuse into one.

What does it mean to be a “composer-driven” organization? If composers are the visionaries of 21st-century opera, what roles do the artists and audiences have in workshopping new pieces?

Jason: A limited number of workshop performances can be helpful, but the tendency for many institutions these days is to workshop pieces to death. Making great art is the ideal. But failing that, bad art is better than good art.

Aaron: One of our values is getting works to the stage on a fairly short timeline. This means that we commission new works and try to get the finished works up within a year. This supports one of the larger goal of composers in general, which is to keep making new music and hear what works and what doesn’t work. This iterative process is so different for the performing arts as compared to the visual arts. Since it takes so much energy and cooperation to realize an operatic vision (as opposed to a sculptor alone in her studio), it often means that composers don’t make that many operas. We are trying to change that. I would like to think that composers can make operas with the same regularity that they make string quartets, or song cycles, or solo piano pieces. This will help to push the art form forward and break down the idea that operas are capstone projects or only once-every-ten-year projects for composers.

Matt: Grand opera seems trapped in grandiosity and makes too many compromises for the large parties involved. In leaner and more experimental works, innovation and the spirit of artistic vision can guide the decisions, hopefully leading to more unique work that widens the scope of possibility in all areas of opera. We offer a chance for a composer to present a personal vision of opera in order to both execute their concepts and attest to their timely relevance: new ideas unadulterated and never stale. EiO’s preference for “Compact Operas” streamlines the workshop process and present audiences with a more direct vision.

What do you think makes for a successful opera?

Jason: Operas succeed when the artists are able to make audiences care about their concerns and interests. Of course not everyone responds to operas the same way, but when we enjoy a work we are appreciating some aspect of the artists personality. In derivative work artists draw from a limited range of influences whereas with more authentic work artists are informed by a unique combination of sources and from their own personal trajectory.

In the past couple years my thoughts have been returning to my childhood growing up in Flint, Michigan. So I’m writing a murder mystery that takes place there during the 1980s. It’s not autobiographical. I didn’t base any of the characters on specific people, but I drew aspects from many different people I knew, and I tried to create the kind of characters who aren’t usually represented in opera. In channeling these people and certain events in my life different themes emerged: personal transformation (especially mid-life crises), the power that historical forces have over the lives of ordinary people, and the death of the middle class.

I’m also in love with the sound world of certain podcasts so I decided to make this work into a podcast opera. The soundscape of the opera includes not only spoken dialogue and the sound design of podcasts but also singing and the textures of instruments I love: pedal steel guitar, modular synthesizer, bass, drums, etc. There’s also comedy, science fiction, and a lot quirkiness in it, so it’s not a typical opera and it’s probably not for everyone. My hope is that I’m able to bring these disparate elements into a whole which people are able to relate with and that they will feel a connection to it. I have feared that making such personal work could be deemed self-indulgent, but the more I have thought about it, I realize that self-indulgent art probably happens not when artists reveal themselves but when they try to hide themselves.

Matt: I think there can be a difference between a successful opera and a successful operatic experiment. Most successful large operas usually have an idea of “success” steering from the beginning, i.e. built into the financing and conception of the piece. This often leads to great works, but recycles the tropes of “great opera.”

In an experimental setting, we can define our goals differently: did our new opera successfully challenge the cliches in opera? Did we convert any listeners, or broaden their minds about opera? Did we do something unprecedented in opera and pull it off musically and dramatically?

Comments