Michael Christie: new opera that the box office loves

InterviewSelling out new opera

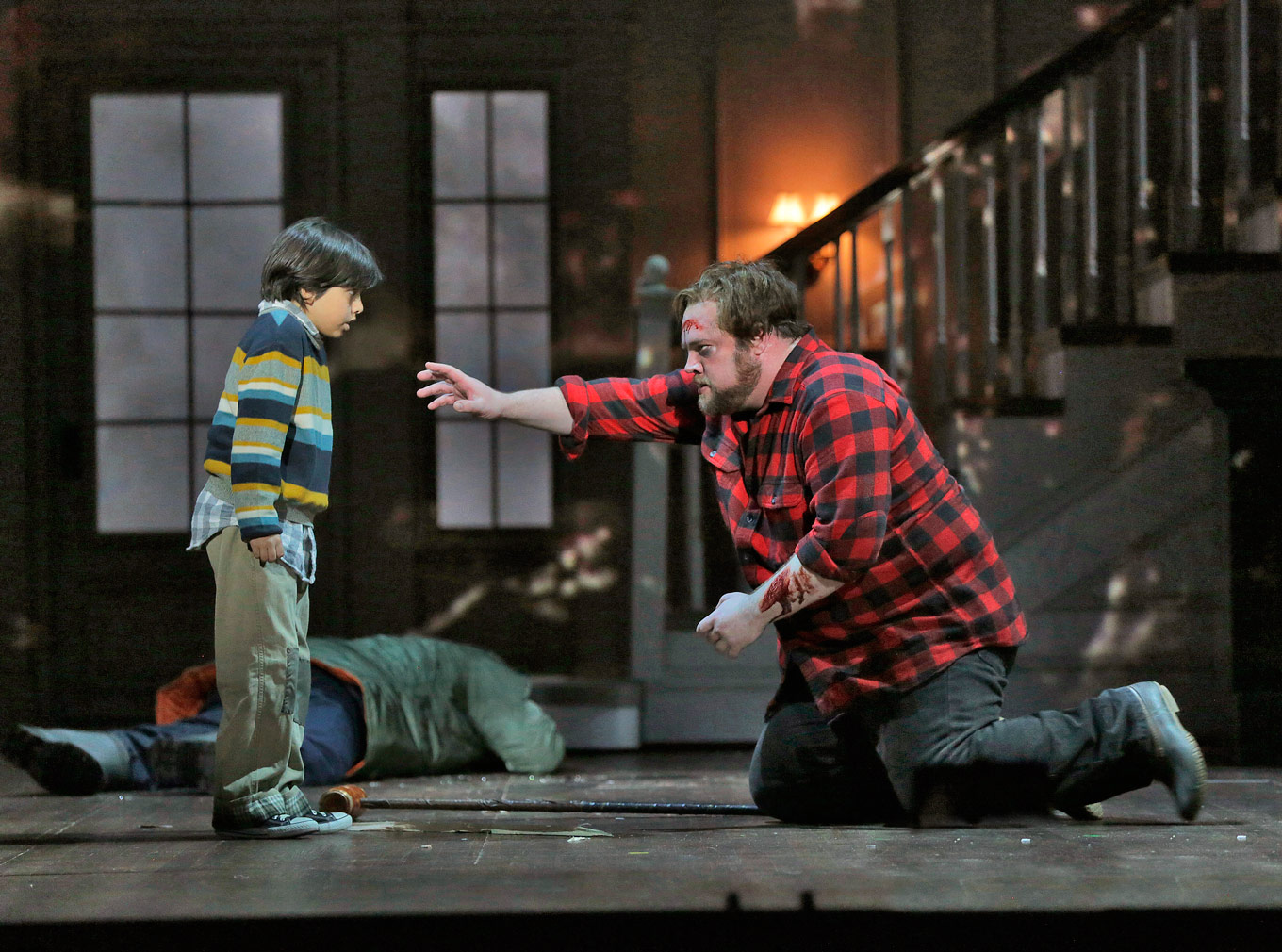

“We often don’t tell our communities what opera is; we leave it for them to decide.” Michael Christie, Music Director of Minnesota Opera. The company has become an American champion of new opera, presenting world premieres on a regular basis, including Silent Night, The Grapes of Wrath, The Manchurian Candidate, Doubt, and most recently, The Shining.

It seems, when an audience is left to decide what they deem “opera”, that they respond positively to hearing new works; Christie credits the community surrounding Minnesota Opera for the consistent support. “In some communities, new music doesn’t go over quite as well,” he explains. “Minnesota is a very particular community; I feel very lucky to be there.”

Christie is Music Director at a company which thrives on a programming model many opera houses may deem too risky, or unlikely to attract new opera-goers. He sees two types of opera audiences: one that “you’ve trained very well that La bohème comes every 3 years,” and another potential audience “who says, ‘really, The Shining? as an opera? I have to go see that’.” Christie sees the consistent inclusion of works like Silent Night alongside traditional classics as a way to show the more conservative listeners that they’re not faced with an “either/or” dilemma, but instead, “yes/and”.

Minnesota Opera has hard evidence that new opera is capable of attracting audiences, and even selling out the house. For the spring 2016 premiere of The Shining, says Christie, “standing room and normal seats were pre-sold. The only thing you could get were turnbacks.” He also saw a “crazy demographic shift,” with a big jump in single-ticket buyers, many of whom were notably under 40.

Minnesota isn’t the only house with world premieres to its name; it’s impressive and exciting to hold a rich history of new works, but Christie also values the positive audience reception and strong box office sales. “Not only does it provide great ammunition for partnering companies,” he says, “but also for our audience, to say, ‘if you’re thinking about coming to see a Minnesota Opera production, you might want to think about buying your tickets early.’”

“I think the next little evolution that will happen, at least my hope, is that we start creating original work,” adds Christie. He notes that the source material for many new works comes from “a big adaptation phase”, drawing on existing stories like The Manchurian Candidate and The Shining. He has lots of love for these adapted stories, but they come with their own unique challenges. The Shining is a great example, “because it was absolutely written in stone that [the opera] could not reference the Kubrick film.” For many audience members, the story of The Shining is entwined with visual cues from the film version, like the hotel wallpaper, or Jack Nicholson’s crazy face. So, those charged with turning a book-turned-movie into an opera are faced with questions like, “what are you going to leave out? What’s operatic, what’s not operatic?”

Christie is optimistic that “we’ve built up enough momentum on the side of new work in general that we could actually present something that’s original.” Without existing tropes or expectations, audiences will be free to “see the connection to whatever human condition it is, rather than relying on the fact that it’s the title of a book that they might not have actually read.”

New challenges for singers

With successful new works like Silent Night and The Tempest and Written on Skin making the rounds among major opera houses, there’s a new challenge placed on the shoulders of working singers. With a repertory less focused on Donizetti and Handel, What does a company like Minnesota Opera, look for in an auditioning singer?

Christie insists that the first step for a singer who auditions for a new-work-friendly company, is just like any other audition: start with what you sing best. “The seeming reluctance to just go out there with your absolute best one is always curious to me,” he says. “Just show up with your best aria, do that one first if you can.” While bel canto and Mozart may not be the most accurate fits for companies like MO, Christie and his team are looking for fundamentals like strong rhythmic skills, harmonic understanding of the aria, and perhaps a substantial sound. (“If people show up with some Strauss, that’s going to be handy. We have quite a big space; our halls require some horsepower to get over the orchestra.”)

It’s a valuable tool to include on one’s audition package a contemporary work in English; “I regret when I don’t see that on the list as an option. So I’m encouraging people to keep hunting for ones that really speak to them.” Minnesota in particular puts the singers of its Resident Artist Program to work, often on world premieres; that means that storytelling is high up on MO’s list of priorities when searching for new talent. Christie asks, “are you tentative, are you brave when it comes to those works, can you sell something that we don’t know at all, and can you make us feel like you know what you’re doing?”

The works themselves offer technical challenges to any singer, and Christie notes that the idea of vocal Fach holds less meaning than in traditional repertoire. “I never hear composers talking about it, frankly,” he says. “There are some composers who do really write with a Fach in mind, but it’s not many. They think ‘female generic soprano’, and then they’ll usually push the range quite heavily in either direction.”

Fortunately for singers, the aesthetic for new works has shifted towards being more melody-friendly. In North America, influences like jazz and musical theatre have resulted in more harmonic resolutions, and even some hummable tunes for the audience’s post-premiere enjoyment. “Not only the singers, but the producing companies have started looking purposefully for people who have that disposition,” agrees Christie. “I rarely have heard an opera audience say, “that’s just crap because it sounds like musical theatre.” I’ve often heard them say, “Phew, a tune, that’s great!”

The future is bright

Though the musical language may be changing, Christie still sees the fanaticism in opera fans that seems to be a historical staple of the genre. Yet, he adds, “I hope that we’re at the beginning of a number of different interesting off-ramps.” He looks forward to the days when, in a single season, a company will present a brand new work, alongside a revival of another contemporary piece that has made it through its workshop trials. “When that work replaces some other work that you put in as placeholder, because you don’t have anything else in your season that works, and you suddenly put in ‘XYZ opera’ that’s cheap to put on or something,” he explains, “then you give your audience an opportunity to see two new works that are really impactful stories. When that starts becoming a growing proportion of our season, that’s when I think the victory will really happen.”

Simply put, Christie anticipates the seasons where 21st-century opera is just “normal”. “I don’t think that’s far away, because there’s enough work that’s out there that we know audiences love.”

Comments