Michael Tilson Thomas takes on Ruggles: Mozart & Mahler

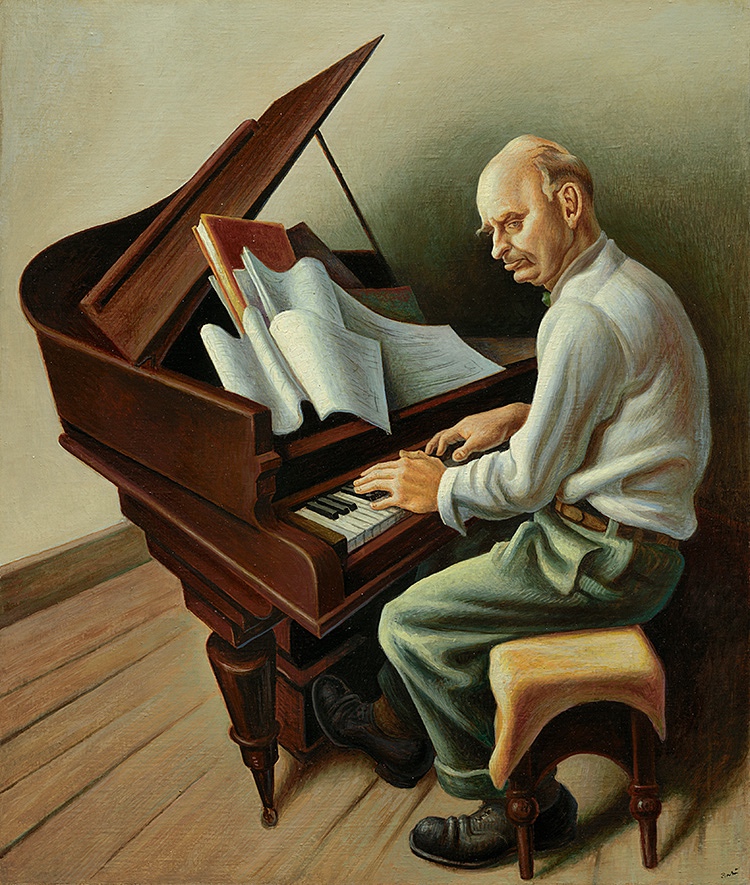

ReviewMichael Tilson Thomas, an effective communicator whether with baton or microphone in hand, opened the final concert of the MET Orchestra’s series at Carnegie Hall, with fascinating comments on the American composer, Carl Ruggles, who was both an iconoclastic and remote personality. Thomas knew Ruggles as well as anyone could get to know this feisty Yankee, prone to being stubborn, cranky and downright disagreeable. Nonetheless, Thomas championed Ruggles, recording his complete music with the Buffalo Philharmonic and including his works with some frequency on programs in San Francisco. Despite his disposition, Ruggles earned the respect of Thomas and many other creative people including composer, Charles Ives and the artist, Thomas Hart Benton, who painted his portrait.

Having set the scene for a discerning audience, it was instructive and genuinely thrilling to hear Thomas gather the forces of the MET Orchestra to take on Ruggles’ Evocations, a four-part piece originally written for piano and arranged by Ruggles for orchestra between 1937 and 1943. He never finished the orchestration, resuming work instead on the piano version. The orchestration is deep and lush with strings and brass vying for attention. Unabashedly atonal, it is devoid of any standard compositional convention with its only points of reference residing in the mind’s eye. Abstract expressionist painting comes to mind when approaching Ruggles’ music; Jackson Pollock’s spattered canvases that achieve their own meaning as times passes and they endure. If true poetry resides in a fertile imagination, then this is music leading us to creative pastures. It was the kind of opening that wasn’t simply rousing, or dutifully getting the new music out of the way, (an unthinkable notion with Tilson at the helm) but one that enriched the pieces to follow.

This thunderous and essential work was followed with an short interval when the orchestra shuffled itself and materialized, reduced in size, ready to take on Mozart’s soaring Exsultate, jubilate, featuring the brilliant young coloratura, Pretty Yende. With its crisp strings, bright woodwinds and Tilson’s brisk pacing, one could be forgiven for thinking that the orchestra was playing on 18th-century instruments.

Yende’s clear and supple voice embraced the high and low ranges of the arias, the delicate passages in the recitativo, and, with a remarkably smooth shift in personality, a hymn-like reverence in “Alleuja.” With her commanding warmth and expressiveness, Yende was not about to become a placeholder between the Ruggles and, after intermission, Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, in which she sang “Das himmlische Leben,” (“The Heavenly Life”).

Perhaps by design, it was difficult to put Ruggles’ Evocations aside as Mahler’s festive sleigh bells and twittering flutes opened the symphony. By comparison Mahler seemed the picture of organization, far-flung perhaps, but there was form emerging. This was partly due to general familiarity with his first three symphonies, and supported by the song in the final movement of this work that reinforces its previously expressed themes.

Yende established a distinct, but not overly operatic manner singing from the point of view of a child in paradise. Mahler’s is a curious and imperfect view of paradise. This is in keeping with the composer whom we have come to know and continues to mystified us. There was no such explanation, even a vague one, with Evocations, in which one waited, unless already familiar with the work, with the kind of unknowingness that is akin to true adventure.

The anticipation with the Mahler was not whether or not Thomas would keep it all in check, but how he would do so. How would Thomas cope with the intermittent nostalgia, the romantic irony and sudden bursts of destiny? In the end it was about his his ability to show that Mahler was sending up grandiose finales without sounding merely grandiose.

Thomas has become one of the leading proponents of Mahler, perhaps by learning to interpret the composer’s building blocks for the clues that they are but not expecting any conveniently conclusive answers. Any personal imprint that Thomas leaves on the work lies in the lucidity that he provides. He doesn’t push for conclusions.

Yende’s impressive vocal agility was an invaluable asset. The naive and rueful charm that she brought to “Das himmlische Leben,” helped the symphony close on a note of stunning transparency. Compatibility between conductor and soloist was uncanny. This is a singer whose range has yet to be fully tapped. Most recently Yende impressed Met audiences with a delightful Adina in L’elisir d’amore and an affecting title character in Lucia di Lammermoor. Here she brings signature intelligence and commitment to the concert stage.

For Thomas, having known Ruggles, who dwelled in impressions, imagination and obsessive reworking, does not make it easier to harness Mahler’s divergent attitudes and points of view. But it likely provides useful insight and patience with the unknown. This symphony, once regarded as confounding and now viewed as one of Mahler’s more accessible works, has benefited from Thomas’ interpretation. Evocations is only 12 minutes long but it permeated the evening.

Comments