Opera is artifice: Giulio Cesare's conquest of Houston

ReviewOnce upon a time, I was a huge fan of Sierra city-building strategy computer games, most particularly the Egyptian-based Pharaoh and its sequel, Cleopatra. With scenarios posing timeless and diverting lessons about economics, geography, urban planning, and especially history, they are very keenly calculated to give a great deal of education to the young, developing mind, while remaining sophisticated to the adult mind even two decades after their initial release.

Given the fascination with ancient history that these games instilled in me early on, it will come as no surprise that George Frideric Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto was the first opera I ever saw live, when Houston Grand Opera presented it back in 2003. The ever-inquisitive 12-year-old me just had to see what Handel did with the captivating narrative of Caesar and Cleopatra. My life was never the same since then; my fascination back then has predisposed me to Baroque opera as not being at all formulaic, but entirely organic in the right hands.

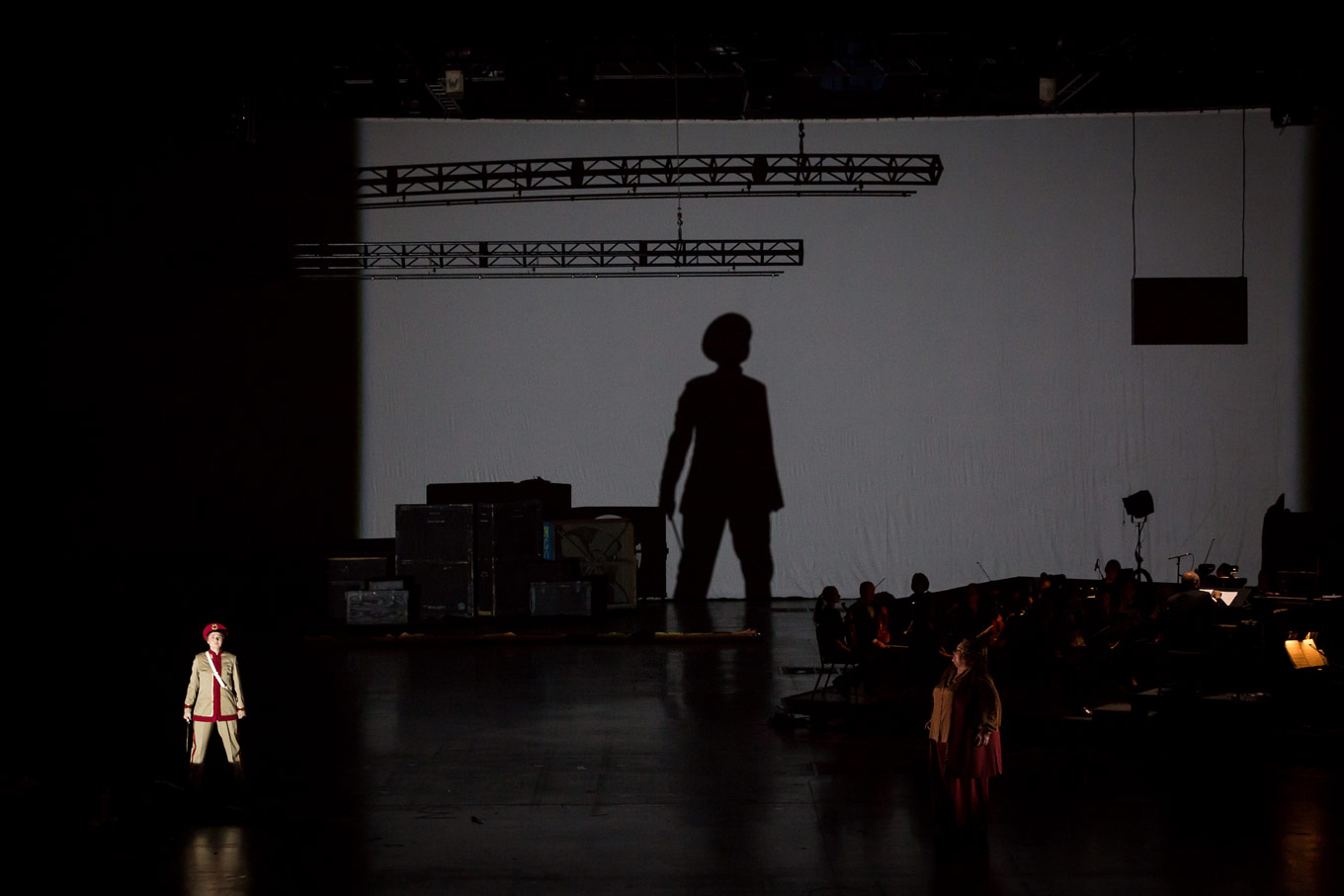

Imagine my excitement, therefore, when I saw that the production I had seen 14 years ago was coming back to Houston in this extremely momentous year, and especially in the newly appropriated Resilience Theater. A certainly apt name in this context, as certainly Cesare’s (Anthony Roth Costanzo) miraculous escape from being swept away in the waters of the Nile can also be interpreted as a symbol of water-battered Houston’s resurgence from its most recent natural disaster.

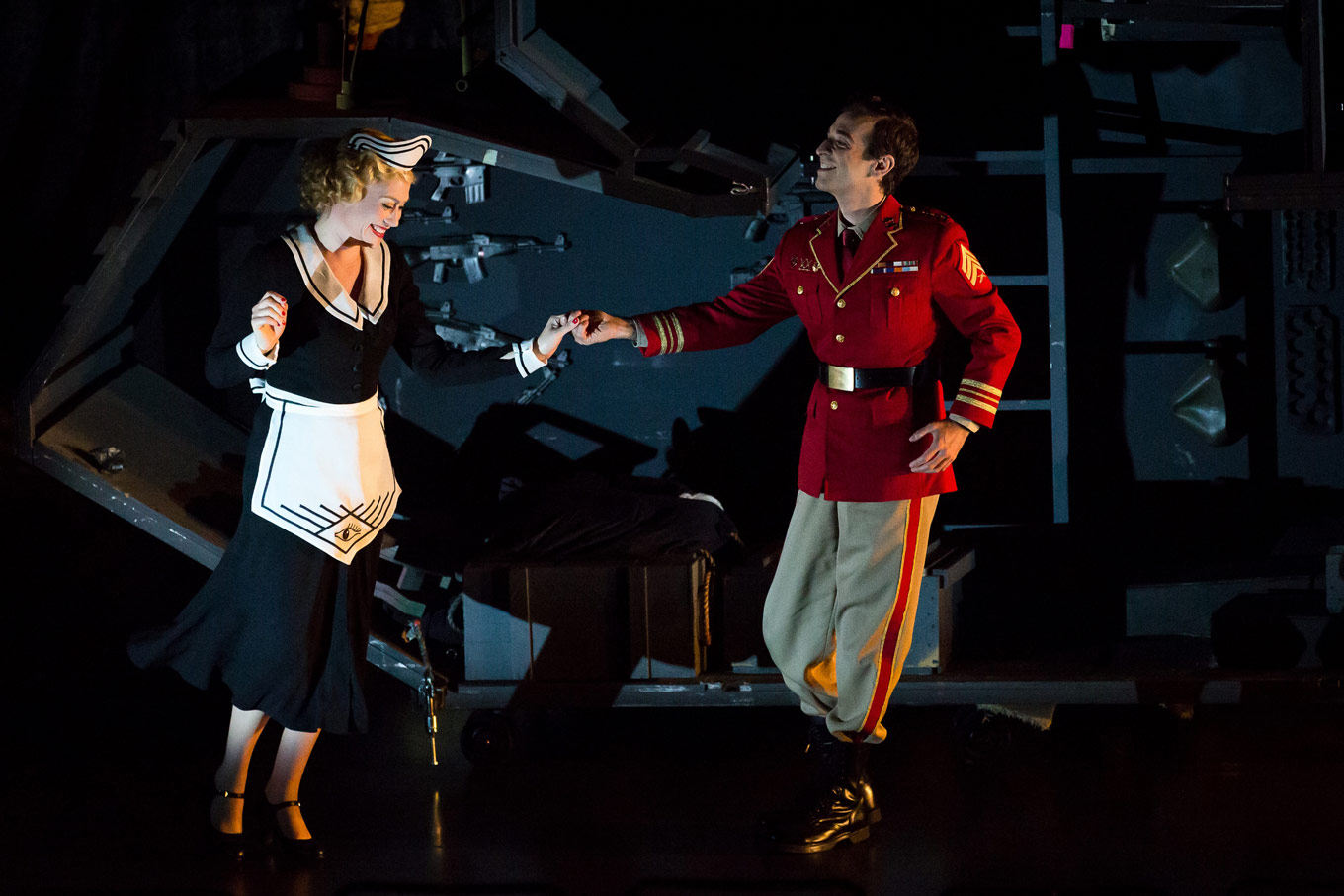

The production by James Robinson takes place on a Golden Age film set, and indeed, the opening chorus showed the cast posing for their obligatory introductory cast photos in front of a film camera, each in turn, followed by Cesare’s triumphant entrance on a stylized battle tank. Different scenes could be visualized as different set rooms of different shape and size. Also evident were numerous clapper operators to signal when a new “take” was starting. Indeed, the characters’ movements were highly exaggerated at times to mirror the sort of movements required in that day to convey emotion, as in opera before the days of electric lighting, thus bringing home the metaphor that opera is very much like film in being delightfully all about artifice.

Costanzo’s take on the title role, which HGO’s Thursday Facebook release went to great lengths to publicize as a take on Indiana Jones, was very effective indeed, in spite of this whimsical comparison. He well personified the countertenor as young virile male hero, particularly being skilled in the arias that showed off his agility and fiery, piercing upper register. He was very versatile on stage, being a visual exponent of Graham Greene’s maxim regarding the need to have multiple changes of clothes in order to be all things to all people. Indeed his onstage antics with solo violinist Denise Tarrant in “Se in fiorito prato” revealed him to be fleetfooted likewise. His ability to sing long cantabile lines was also prodigious, “Va tacito e nascosto” showing this off particularly well, with an expertly delivered obbligato by Acting Principal Hornist Spencer Park, who followed along with Cesare’s increasingly elaborate, yet effortless arabesques with equally deft finesse. Composers wanting to write horn concerti, take note of this virtuoso!

As Cleopatra, Heidi Stober well personified the versatile diva-actress in several emotional frames of mind. Flirtatious, melancholy, disconsolate, conniving, ecstatic: these are all words that describe the sorts of characteristics at which any Cleopatra must excel at portraying at some point, and she did so with aplomb. Especially in agile arias, her natural charm showed forth effortlessly, though this did not preclude her slower arias being rendered with genuine emotion. Her “V’adoro, pupille,” featured an incredibly captivating visual trick, with numerous supernumeraries surrounding her in the shape of a pyramid to create the impression of her emerging from one, and her voice created the impression of coming from some heavenly realm likewise. An additional welcome surprise was a newly created bassoon obbligato for her Act II aria “Se pieta di me non senti,” supplied especially for this performance by principal bassoon Amanda Swain, quite natural and worthy of standing alongside the best of Rameau’s bassoon obbligati.

I was obviously interested to see what David Daniels, who introduced me to the wonderful world of countertenors in the role of Cesare so many years ago, would bring to the role of Cleopatra’s famously petulant, spoiled, whining brother Tolomeo. Indeed he delivered the goods at every opportunity, particularly in terms of sheer acting flamboyance. Daniels’s agility and tone were very much in evidence to make this character into a highly enjoyable cartoon villain, in which different shades of pettiness were brought to the fore at will.

Stephanie Blythe as the ever-mourning Cornelia had a suitably resonant low register, very suitable for her brooding arias which effectively frame her perpetually suicidal outlook; I was reminded at many turns of Marie-Nicole Lémieux. Her duet with Sesto (Megan Mikailovna Samarin) was another of Handel’s characteristically poignant moments, in which the onstage film cameras surrounded them to give the impression of filming a closeup, poignantly emphasizing their isolation and despair.

As Sesto, Samarin was entirely convincing in this monomaniac character. I well remember her arresting performance as Marzia in Glimmerglass Festival’s exemplary production of Vivaldi’s Catone in Utica, so the fact that she imbued Sesto with feeling was in no way surprising. It is incredibly difficult to give this character any sort of convincing depth, as all of his emotions are seen through the lens of his overwhelming desire for revenge, and it is entirely to Samarin’s credit that Sesto held my unwavering interest. It is to be pitied, however, that my favorite of his arias, “L’aure che spira” was nowhere to be heard.

The role of Nireno was ably sung by Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen, and his aria was one of my very favorites that evening: simple, graceful, assured, yet never lacking in élan. Indeed, I enjoyed the way he routinely bobbed his head up and down in a very graceful, parakeet-like fashion, which his ornate white turban served to accentuate. It gave the impression of his character being ready to say at all times, “How can I be of service today?” I look forward to seeing his upcoming performances with Ars Lyrica Houston based on this first impression.

Bass-baritone Federico de Michelis played the role of Achilla with great flexibility and dramatic nuance. His character sported a black fez which rendered him in this universe exotic, but also menacing, if only to an extent. Anthony Robin Schneider, as Curio, rounded out the cast, and his presence was quite palpable throughout, even when he was not singing. When he did sing, it was with a booming and resonant tone that entirely fit his physical frame.

The orchestra was quite idiomatic in Baroque performance practice for this occasion, which is to be expected, given that several of the string players double as core musicians of the prestigious period-instrument orchestra, Mercury Houston; indeed, Mercury’s harpsichord, an instrument I have often played, was being specially used for this performance to accompany the orchestra, which was actually all onstage for this production. Maestro Patrick Summers did an able job of conducting the ensemble in the orchestral numbers from his harpsichord, which he used to accompany the recitatives in a standardized manner. The orchestral harpsichordist, Kirill Kuzmin, was skilled at accompanying arias unobtrusively, an ability not to be taken for granted, as I will attest. Some persons might be inclined to say that the performance could have generally been fresher and more spontaneous, but I think Giulio Cesare is a work that does not necessarily need excessive finagling of this sort in order to succeed musically, even though being creative with Baroque music is never a bad thing.

My conclusion is that the Houston Grand Opera should certainly consider using the Resilience Theater space in future for productions featuring similar levels of intimacy. When the company advertised this space as one that would get the audience to be integrated in the theatrical process as never before, I wager this is the sort of production to which HGO was referring. Though they succeeded in bring the music genuinely to life a precious couple of times this evening, this production was an object lesson that an enlivened cast and production is enough to render a well-worn repertoire work immediately appealing.

HGO’s Julius Caesar runs at the Resilience Theater through November 10. For details and ticket information, follow our box office links below.

Comments