Orlando: gender bending and the sound of androgyny in Vienna

ReviewMrs. Dalloway would have been my bet for an opera based on a work by Bloomsbury modernist, Virginia Woof. That-stream-of-consciousness treatise tracking the inner thoughts of a London society matron as she shops for a dinner party fairly yearns for languid arias linked with moist recitative and perhaps even an introspective monologue.

Instead, composer Olga Neuwirth chose Woolf’s Orlando, her often funny faux-autobiography about a young nobleman in the court of Elizabeth I who awakens one morning as a woman and proceeds to roam about time and space for the next 300 years. Orlando, along with Flush, Woolf’s subtle criticism of urban life disguised as a biography of a cocker spaniel belonging to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, serves as a gateway to the renowned writer’s more esoteric works.

But Neuwirth wasn’t looking for a gateway to the esoteric. She sought a platform to launch an opera that is thoroughly unconventional in thought, sight, sound and certainly linear storytelling, one that would catapult the driving issue— the recognition of androgyny in both gender and sound. Orlando landed on one of Europe’s most grand if conservative stages, the Vienna State Opera. It is the first work produced by a woman in the company’s 150 year history.

Such was the storm that swept through the opera house this past December when Orlando premiered. It was later streamed for three days on staatsoperlive.org, which accounts for its availability as an unauthorized DVD. A sanctioned video release would be most welcome, especially if it was accompanied by commentary from Neuwirth and notes from the production team, chiefly by costumer designer Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons, whose creations play more as sculpture than clothing, and videographer Will Duke, who designed a range of panoramic and finely detailed video to evoke the far flung times and places that the libretto by Neuwirth and Catherine Filloux require.

The curtain has barely risen on Orlando and suddenly the orchestra in the pit is sharing space and music making with electronic instruments and recorded samples. At times one legitimately wonders where the sounds are coming from and what or who is making them. Second violins are tuned a tad lower than the first and what sounds like a classic English boys’ choir on stage is met with shivering electronic sounds before it becomes immersed in the dissonance of a competing choir located in a space above the auditorium. Orlando is filled with musical moments like these, some fleeting, others nearing thematic status which reinforce Neuwirth’s stance on androgyny and makes the orchestral writing so compelling.

In harnessing Neuwirth’s score, contemporary music leader Matthias Pintscher created a kind of miraculous flow that captured the work’s often raucous style. Composer/conductor Pintscher knows from whence Neuwirth is coming. Watching a performance of his composition Sonic Eclipse that he conducted with Ensemble InterContemporain of which he is music director, is to understand his keen ability to communicate contemporary music not to mention the unorthodox sounds that his musicians must produce to realize his work.

Polly Graham who assumed direction only seven weeks before the opera’s opening, is sleekly in sync with Pintscher and with the cascade of video that Duke has designed. Graham, the artistic director of the Longborough Festival Opera and the socially and politically progressive Loud Crowd opera company possesses the directorial attitude for which Neuwirth and the Vienna State Opera were surely looking.

But after everything Orlando has too much plot. Woolf’s book ends on October 28,1928, ostensibly the day the novel is published. The opera ends on the day of each performance. Between 1928 and then, or rather now, much is added that begins as well-intentioned shouts for attention to climate change, sexual abuse and the rise of populism among other things, but ends feeling more like discarded placards for progressive causes. Even the music pales by comparison to the jangle of organized chaos that has preceded it.

What Woolf and Neuwirth make exceedingly clear is that Orlando’s sudden change from male to female brings about an abrupt lowering of her status. That should be enough to carry Neuwirth’s message on androgyny forward. Instead we get a litany that fails to reach us with the exception of the advent of World War II and the projection of the names of Holocaust victims. At this moment the score appropriates a recording of the slow movement of Bach’s double violin concerto played by Arnold Rose and his daughter Alma, who perished at Birkenau in 1944.

Unfortunately this moving scene halts the opera’s action. That exciting flow that Pintscher and Graham developed is never fully regained.

Kate Lindsey, that mesmerizing mezzo-soprano, is Orlando, and what virtuosity she exudes, even while being a part of what sounds like a vocal miscalculation. No stranger to trouser parts, having most recently wowed Metropolitan Opera audiences as a punky Nerone in Handel’s Agrippina, Lindsey dazzles with her low register when Orlando is a man. She is required to sing in a much higher range after transforming to a woman. At first the change and the impressive manner in which it is sustained seems spectacular and vocally it is a benchmark in Lindsey’s career.

But I wonder, if Orlando is truly androgynous and the opera’s androgynous spirit is to be maintained, if the voice would rise so radically. Lindsey is on her own to delineate character and she does so with adroit intensity. She burns as Orlando the female and does so brilliantly, regardless of the appropriateness of her singing range. Due to the abstract and counter-intuitive grandeur of Kawakubo’s costumes designs, likely attention-getting from outer space, they don’t really establish character or place.

If this star of cabaret is uncomfortable on the operatic stage, it doesn’t show.

When speeding along full-throttle, Orlando is populated by a remarkable group of characters. The queer cabaret artist Justin Vivian Bond, clad in a sheer black Comme des Garcons gown plays Orlando’s child, a character that does not appear in the book. While not an operatic performer in any sense, Mx. (gender neutral honorific preferred) Bond is a distinct presence who positions attitude like a laser. If this star of cabaret is uncomfortable on the operatic stage, it doesn’t show.

There are several standouts in the large and generally excellent cast. Countertenor Eric Jurenas serves as Orlando’s Guardian Angel who watches over him from the very beginning. Soprano Agneta Eichenholz is Sasha, Orlando’s first love who runs off with a Russian sailor during the Great Frost. Later she appears as Chastity, one of three women who visits Orlando after he vows to become a poet and falls into a deep sleep. Baritone Leigh Melrose appears first as Orlando’s husband, Shelmerdine and then as her publisher, Greene. Soprano Constance Hauman divides her presence among three roles; Queen, Purity and Friend of Orlando’s Child.

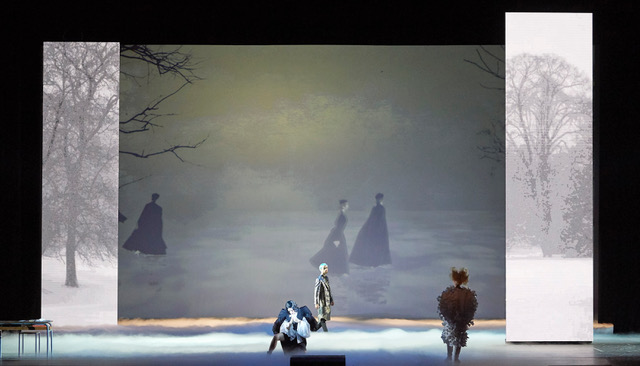

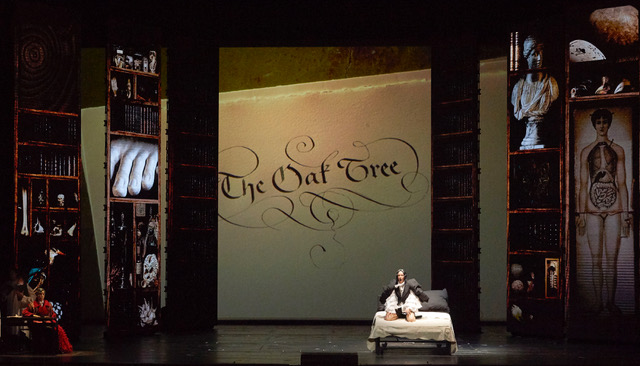

Orlando, a hybrid of fiction and imposed fact, of musical styles so varied it would be easier to mention what is not referenced and of intentions so adventurous as to appear impossible to realize is thrilling opera despite its glitches. What gives it such a strong sense of place, an extraordinary achievement considering that the opera takes place over centuries and almost everywhere, are the visual images that comprise the set or more aptly the places where action transpires. According to Duke, Orlando provided opportunities to utilize all of the tools available to video designers; pre-recorded film, live cameras, animation, photography, graphic design, stock footage and archive footage. A large rear screen projection system is employed with six LED screens that could be configured to meet the video needs.

What the future holds for Orlando is an open question.

Duke says Neuwirth “had very clear ideas about the information she wanted the video to provide during each scene. Because neither the set design or costume design were really providing any narrative information it was important that the video was able to convey some of that to the audience.” He adds “We thought that incorporating such a range of styles was appropriate for the way that Olga had written the score for Orlando. Musically she references so many styles and periods of music so we wanted to try and mirror that with the images.”

What the future holds for Orlando is an open question. As it stands it deserves further attention and after some judicious editing and rethinking of Orlando’s singing range, could well become a template for opera’s post-modern future. Opera needs a voice that speaks not only to the future but to an unpredictable and exciting one. Olga Neuwirth comes through loud and clear.

Comments