Playing bel canto: 4 tips for pianists

How-toGet literal

For as stretchy as it sounds, bel canto scores are surprisingly systematic. Pianists tend to like everything to line up in nice vertical chunks, but a better rule of thumb is to simply keep playing until told otherwise.

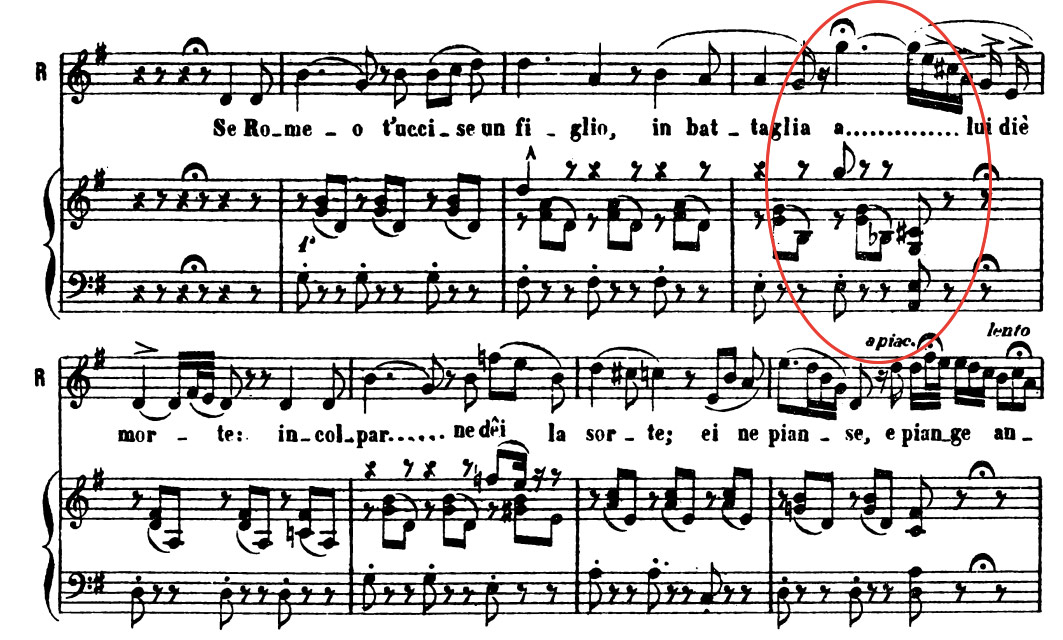

In this bit from Bellini’s I Capuleti ed i Montecchi, there’s a fermata for Romeo on beat 2 of the bar, and a fermata for the orchestra/piano on at the very end of the measure. The idea is simple: the orchestra wraps up what it’s doing without too much fluff, while Romeo hangs out on his/her high G. This way, the singer has complete control over the descent coming down from the high note, and the tempo kicks back in at “morte” in the next measure.

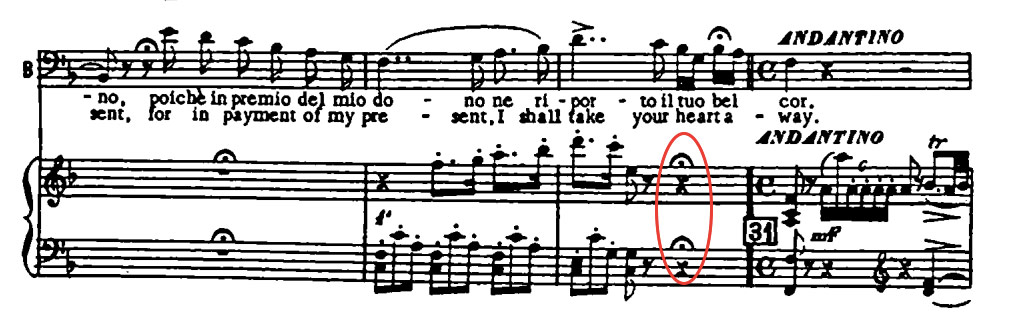

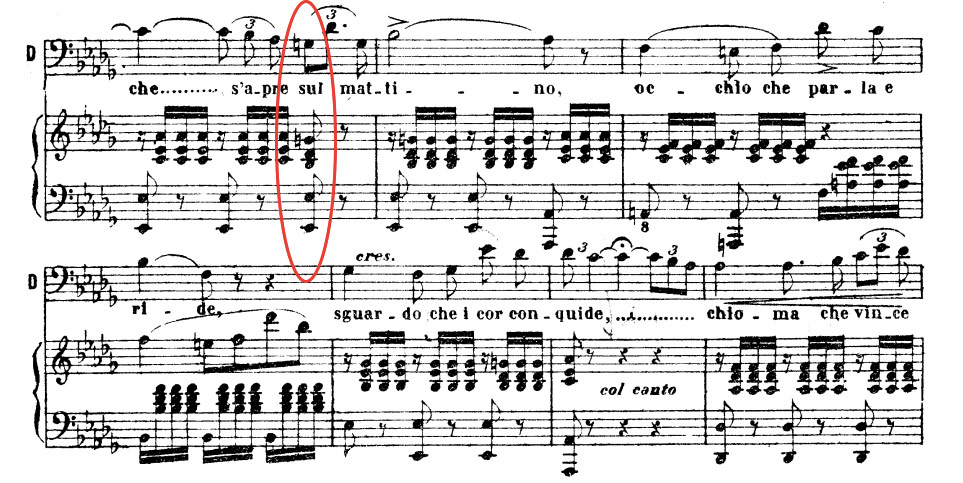

Another example, this time from Belcore’s aria in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore:

The orchestra has a bar and a half of music between fermatas, to give a bit of structure Belcore’s little mini-cadenzas. As a sensitive pianist, you may be inclined to taper off the tempo leading up to the fermata (circled in red). As a bel canto pianist, resist that urge. It’s stylistic - for Donizetti, and for the context of this aria - to stay pretty metronomic unless you’re told to do otherwise. Again, with the orchestra/pianist out of the way, Belcore has more room to show off his stuff.

Think like a conductor

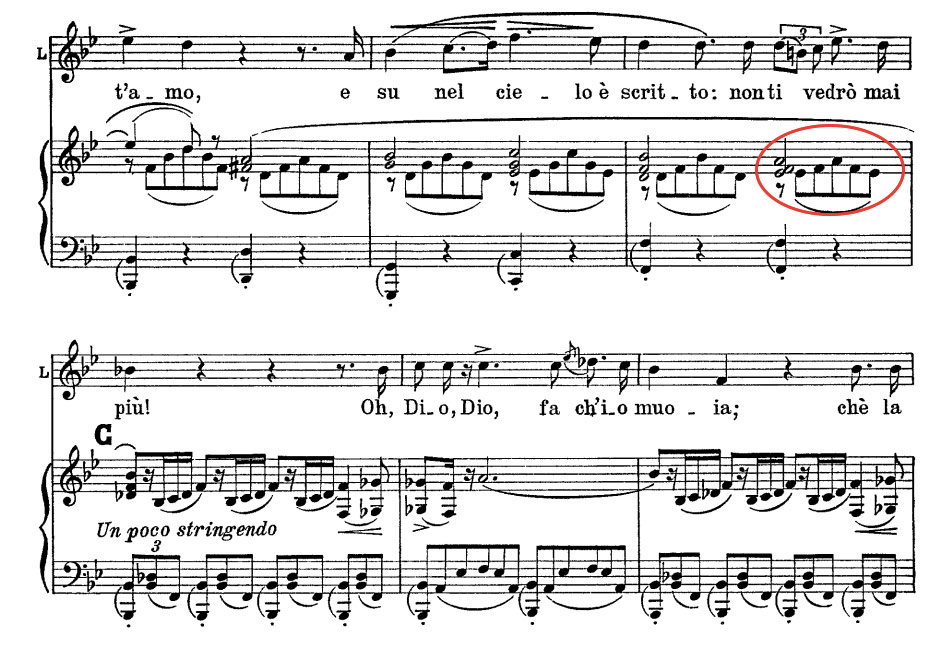

The notes of bel canto accompaniment may be simple, but when rubato comes into the mix, it’s often tricky to know when to play them. This moment from Leonora’s “Pace, pace” (La forza del destino) is an example where the music warrants a bit of stretch over “vedrò”, even though the score gives no such indications. A conductor is likely leading the orchestra in a leisurely 4⁄4 pattern, and the harp is dividing each beat into triplets in those arpeggio figures.

When everyone gets to this stretchy “vedrò”, the question is: where does the conductor have the orchestra wait? Does the harp pause on the first triplet of beat 4 (the A-natural), and then fill in the other two when they see the conductor’s hand start to come down? Or does it truck right along to the final triplet (the E-flat), and wait there on the ready for the a tempo? In some cases - likely not this one - a conductor might even show each triplet of that beat; the effect is more deliberate, and it’s ironically not as flexible as the other two options.

Pianists, you have this choice to make. It doesn’t matter if you side with the majority of conductors; what’s important is being able to conduct whatever you choose to play. If it’s awkward to show with your hands, it’s likely awkward to hear.

Keep it simple & stay out of the way

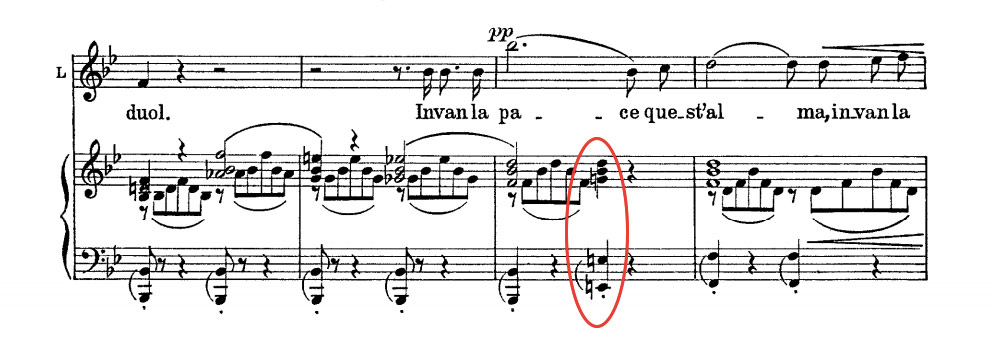

Here’s another section of that same aria from La forza del destino. It’s a spot where a soprano may feel like hanging out for some extra time on that high B-flat - and really, who are we mere mortals to stop her?

Even if you, the pianist, have it on good authority that your soprano will indeed extend that high note, it’s kind - and wise - not to paint her into a corner. As you play this bar, stay in time right until that rest on the 4th beat. For a singer, there’s something terrifying and trap-like about hearing their pianist slow down while they’re in the middle of something tricky. It perhaps more psychological than physical, but a pianist who tries to stretch out the whole bar (even with musically-inclined intentions) can actually psych out the singer and cost her breath control when she’s stuck up there on that B-flat.

In short, pianists, play your bit and let it be robotic - let the singer take all the glory (because they’ve worked harder for it).

Know when to take the reins

Lest you think that bel canto is about giving total power to the singer at all times, check out this example from Dr. Malatesta’s aria in Don Pasquale:

A lot of baritones like to get away with some stretchiness on that D-flat on “sul”, and snap back into tempo at “mattino”. Totally legit idea, and pianists should be ready to wait a little bit longer in that rest at the end of the bar. But sometimes baritones start to pull back the tempo too soon, slowing down the triplets on “s’apre”. It’s not a grave error by any means, but it makes the bar plod instead of pull, and it’s frankly less funny.

In cases like this, a pianist (standing in both for the orchestra and the conductor), wields some power. You should try and drive your singer forward, staying a tempo until beat 3 of the bar. The stretchy moments in bel canto are only really effective if they’re done within a context that’s rhythmic; in this case, an unforgiving pianist can actually give the singer a better set-up for an indulgent moment.

Plus, there are the practical things to consider: if a baritone were to sing this aria with an orchestra, a conductor would be less-than-thrilled about having to pull back beats 2 and 3; it’s cleaner, easier, and more stylistic to truck ahead until the orchestra’s rest, and let Malatesta do what he does in his mini-moment on that D-flat.

Comments