Reconstructing a lost opera: Amleto

InterviewWhen it comes to the opera stage, Shakespeare gets his share of representation. There’s Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Thomas Adès’ The Tempest, and of course, Verdi’s Otello and Falstaff. There’s also Hamlet, the opera by Ambroise Thomas, but did you know there’s an Italian Amleto (#essereononessere), composed by one of Verdi’s contemporaries with text by Shakespeare-friendly librettist Arrigo Boito?

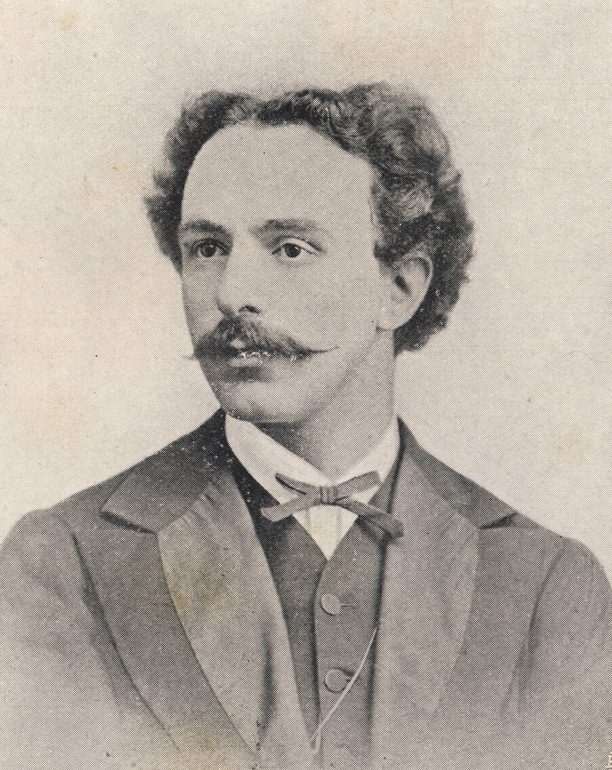

Conductor and composer Anthony Barrese has spent a good part of the last decade reconstructing and creating a critical edition of Franco Faccio’s lost opera based on the Bard’s most famous play. Amleto was lost after Faccio withdrew it, following less-than-stellar reception during its 1871 remount. Amleto was finally produced again in 2014, at Opera Southwest in Albuquerque, NM, and in May it goes up as part of Opera Delaware’s 2015⁄16 season.

Barrese was kind enough to talk about how he revived Faccio’s lost opera, and what it was like to see it onstage. For more on Amleto, click here.

1. How did Amleto get “lost”?

The short answer is that after the 1865 premiere in Genova, the 1871 remount in Milan was a disaster, sufficient enough to inspire Faccio to withdraw the piece and never have it performed again in his lifetime.

Contrary to standard practice, the publishing house Ricordi never got around to making a piano vocal score of the entire opera, and published instead a handful of arias and duets. Other than these excerpts, the only musical source was the composer’s autograph manuscript, which is what I used to reconstruct the score.

2. What was your process of restoring the opera? What information did you have, and what were you missing?

I started with the libretto which now is available through google books online, but 12 years ago had to be gotten the old fashioned way. My wife was in NY in the summer of 2003 and she went to the NYC performing arts library and found a microfilm of the libretto and had it copied out and sent to me. After that, I was able to get in contact with the Ricordi Archives in Milan and they sent me a microfilm of the composer’s autograph manuscript.

Over a 6 month period I copied out every single note in the score, by hand. At that point I had something resembling a full score. Then I input it all into a computer engraving program. After that, I made a reduction for piano and voice so that someone could play through it. Then began the years long process of editing all the scores I had made. Finding the mistakes, correcting them.

When I first began the process, deciphering Faccio’s handwriting was difficult. By the time I was done, I had gotten used to his idiosyncracies, so things that were a mystery to me in the beginning were now revealed. But that meant correcting a lot of things I either didn’t get the first time through, or mis-interpreted. And it’s a never-ending process. Just 2 weeks ago I was looking through Hamlet’s aria “essere o non essere” and I found no fewer than 5 mistakes in my full score. This is after 5 full edits.

3. Franco Faccio’s work is closely related to Verdi’s, including sharing a librettist. How do the composers compare, and did rivalry exist between the them?

Faccio’s music is more consciously “avant-garde” than Verdi’s. He makes a conscious effort to do something new in Italian opera. There is a lot of heightened chromaticism (showing the influence of Wagner), and a great reliance on the orchestra to set the mood for every scene (again, shades of Wagner). But at the end of the day, it is an Italian opera, so it relies heavily on melody.

For all of their self-congratulatory touting of the “Italian music of the future” both Verdi and Faccio were Italian composers. I will say though that there are real hints of verismo in the vocal writing. Eschewing the fast note virtuosity of, say, a Donizetti, or early Verdi, Faccio relies much more on declamatory singing in the higher parts of the register for the tenor. There are times when Hamlet almost sounds like a proto-Turiddu (Cavalleria Rusticana).

As for rivalry, not much actual rivalry ever existed between Faccio and Verdi. Verdi may have had a bad taste in his mouth about Faccio, but that was really because of Boito’s “Ode saffica col bicchiere in mano” that he dedicated to Faccio and which very directly insulted Verdi. But Verdi did go out of his way to try to procure the rights of a Sardou play for Faccio to set to music, and the year of the disastrous La Scala production of Amleto, Verdi entrusted Faccio to conduct the premiere of his own Aida. Faccio then went on to become the first real music director of La Scala (the “maestro scaligero”), and conducted the premiere of Otello. If had had lived, he undoubtedly would’ve been Verdi’s choice to conduct the Falstaff premiere too.

4. What is the reward for you for taking on the task of restoring a lost opera?

The reward for me came on the night of the first modern performance of Amleto. Both the concert performance with Baltimore Concert Opera, and the full production at Opera Southwest in Albuquerque. It came in the form of accolades from musicians, critics, and audience. It came in the form of other opera companies from Opera Delaware to the Bregenz Festival taking on the work. If the work can eventually enter even just the periphery of the repertoire, that would exceed my wildest expectations.

For details on Opera Delaware’s upcoming production of Amleto, follow the box office links below.

Comments