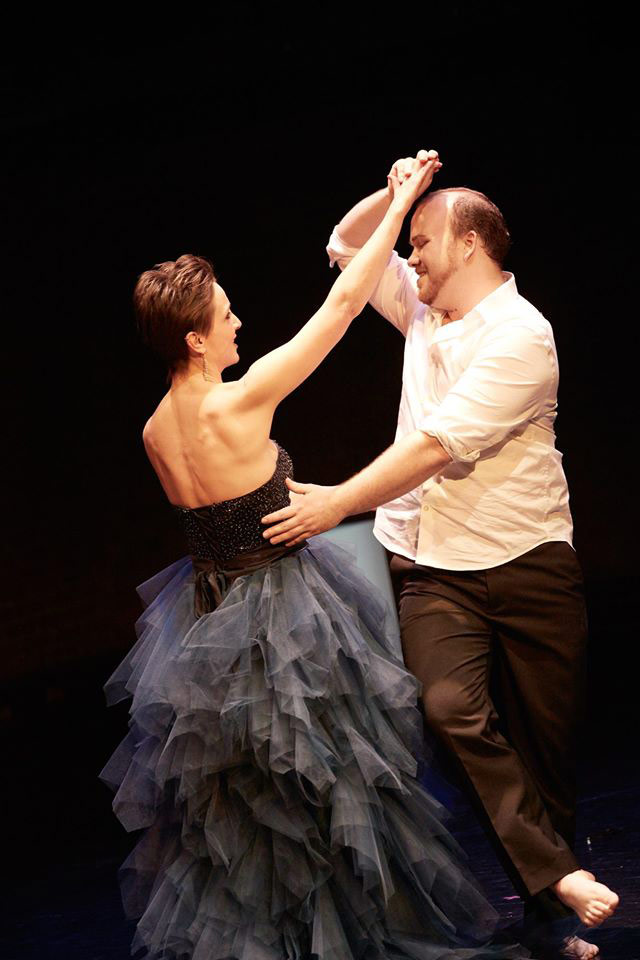

Rehearsing "a Messiah that moves."

Op-edAgainst the Grain Theatre just closed their “inspiring” production of AtG’s Messiah, the company’s staged, choreographed, barefoot take on Handel’s classic that has audiences delighted and inspired. I’m proud to have been a member of the music staff for this show, working with a 16-member chorus, 4 soloists, AtG Music Director Topher Mokrzewski, director Joel Ivany and choreographer Jennifer Nichols.

That’s why readers won’t find a review of the show on Schmopera, since my investment in AtG’s Messiah wouldn’t exactly make for an unbiased piece of writing. I often reach out to Schmopera contributor Greg Finney to help cover the shows I can’t - this time, Greg was in the AtG chorus, meaning he couldn’t exactly be objective either. It’s not hard to find a review of the show (and a great one, at that), but instead, it’s a good opportunity to talk about how something like AtG Messiah is put together.

A production like this has an endless list of moving parts for the performers, for the chorus members in particular. The creative team was conscious of what they were asking of the chorus; they were to perform 15 numbers, off-book, with synchronized movements, while seeing the conductor. The task is colossal. When Handel wrote Messiah, I’m almost positive he wasn’t envisioning a choreographed performance, let alone a memorized one. Memorizing the music alone is a huge feat, especially when it comes to incorporating dozens of notes from the music staff. As we rehearsed the chorus, we asked for specific cut-offs, certain vowels, dynamic levels, and tempo flexibility. These kinds of notes are par for the course for opera singers, but the sheer quantity of music can make a chorus feel like they’re those acrobats who spin plates or juggle 15 bowling balls.

AtG Artistic Director Joel Ivany and choreographer Jennifer Nichols split the work of staging Messiah, and they both shared their rehearsal time with conductor Topher Mokrzewski and myself. A typical order of things would look like this:

- Run the number musically. Get notes from Topher and Jenna. Try it again with said notes. Music staff are pleased.

- Learn a chunk of choreography. Try it without music. Get notes from Jennifer and Joel. Try it again with said notes. Jennifer and Joel are pleased.

- Try said chunk of choreography with music. Get notes from music staff and choreographer.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the number is complete.

- Run the whole number with music and choreography. Get more notes from Jennifer, Joel, Topher, and Jenna.

- Repeat steps 1-5 until opening night.

The method is fairly standard for an opera staging rehearsal, and the fact that it was a constant process of refining details was not unique. Still, it felt like the entire team needed to be hyper-aware, always asking the artists for more precision and beauty, despite how difficult it was. Between director, choreographer, and music staff grew a working chemistry that was sort of symbiotic, a kind of relationship that’s hard to achieve.

There was a constant exchange of vocabulary when we were defining musical landmarks for the movement; dancers count in beats, and singers often use text or musical cues to orient themselves in their staging. It’s a big ask to get 16 singers to move as a unit, but this group became communicative and collective problem-solvers. I sensed how the members of the chorus learned their choreography, and committed it to memory in their preferred way. There were always things to fix, and it was almost impossible to spend time focusing on strictly music or strictly movement. Too many repetitions of the movement, without checking in musically, can reinforce mistakes that get harder and harder to change.

Of course, the final product was something greater than the sum of its parts. Each night, there was that great Against the Grain alchemy onstage, that amazing thing that happens when performers reach out to the audience, and the audience gives back. Some of that giving back, they did on social media; the run has stirred up the usual AtG-show Twitter buzz, full of people loving the imagination in this Messiah.

Godspell meets Frozen meets Handel in moving and entertaining dress rehearsal last night @AtGtheatre for #AtGmessiah - GLORIOUS singing!

— Michael Shannon (@mshanncoaching) December 16, 2015#AtG now stands for Awesome, Theatrical GOLD. What a great night!! @AtGtheatre #AtGMessiah

— Aaron Durand (@Gingervanni) December 18, 2015Nothing says Christmas like a baritone in a shiny gold unitard vogueing to Handel. Ty @AtGtheatre @HegedusStephen

— Catherine Kustanczy (@catekustanczy) December 18, 2015It struck me that the thing holding all of these moving parts together was the fact that everyone wanted to make something great out of all of this work. It’s an energy that can pack a bigger punch for the audience than simply perfecting a musical and physical to-do list. I don’t say this to minimize the work involved in staging a piece like this one. The workload, musical and otherwise, is enormous, and AtG’s Messiah is evidence of opera’s contemporary demand for performers who are efficient, versatile, and brave.

Productions like this, where the audience is close and the concept is novel, are becoming the norm among today’s smaller opera companies. Many of the singers in AtG’s Messiah were working with Against the Grain for the first time; these artists have gained experience within the industry as it looks now. Not every working singer could pull off the detail and the multi-tasking required in intimate spaces and new spins on old repertoire. But the audience’s enthusiasm is hard to ignore, and it seems that the bar for lyric theatre has officially been raised.

Comments