ROH's Madama Butterfly: better to be furious than bored

ReviewThere are few things more emotionally confusing than watching Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. One man seems to embody all that is stereotypically loathed about Americans, and one woman seems to be a shining example of all the horrors that can happen to women, from selective education and naïveté, to having her children taken from her.

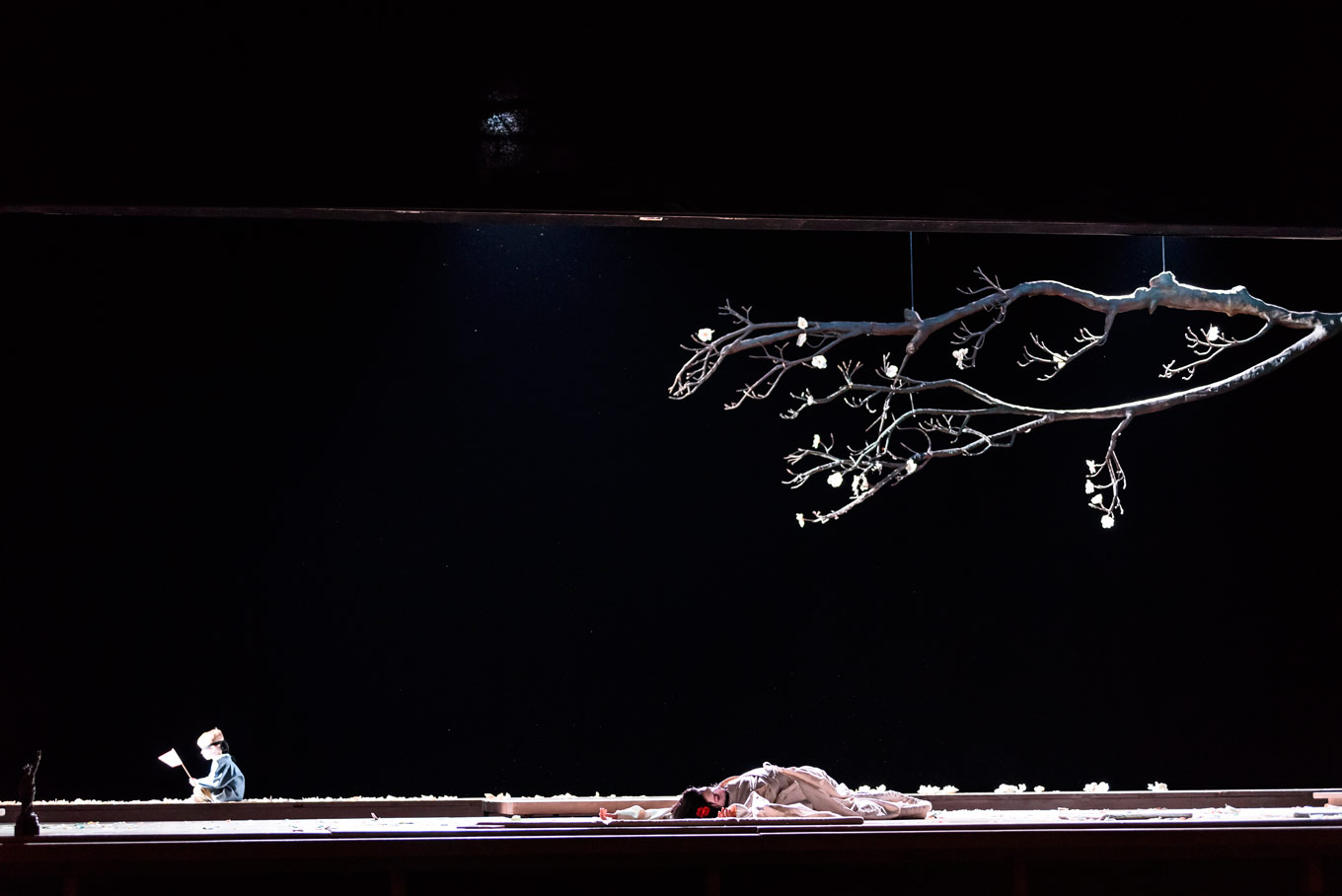

The Royal Opera House is in the middle of its fifth revival of Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier’s production, which contains the action entirely within the sparse, minimal house that Pinkerton rents in Nagasaki. Antonio Pappano’s brisk tempi allow the action to move at a realistic pace, and when he takes time to enjoy a moment (or recoil from it), it packs an extra punch.

Late to the party as we may be, this was our first chance to see the 15 year-old production of Butterfly. The sparse set design brings fantastic focus on the people in this story, and it seems to heighten everything that’s uncomfortable and tragic. Carlo Bosi is a strident Goro, a confident salesman with a voice that seems almost too loud for the delicate house. Scott Hendricks is an amiable Sharpless, holding on to his precious few moral convictions, in defiance of the more carefree groom-to-be. Marcelo Puente has that infuriating condescension about him as Pinkerton, yet with a pressed sound that was consistently flat, we lost the opportunity to hear his softer, enamoured side.

Ermonela Jaho and Elizabeth DeShong were a beautiful pair as Cio-Cio San and Suzuki. Jaho’s dark voice, though hard to imagine it on a 15 year-old, offers an enormous palette of options, and she had a beautiful path from a doll-like girl to a young woman stripped of all hope.

DeShong’s portrayal of Suzuki is something we’ve enjoyed before, and she truly is an expert at building a character with relatively little stage spotlight. We understand immediately that Suzuki is smart and practical, living within her own trap as maid to a stubbornly hopeful Cio-Cio San. When the two women hear the sound of Pinkerton’s ship arriving, the resulting emotional rollercoaster seems almost harder on Suzuki.

Perhaps a director’s choice, the relationship between Cio-Cio San and Pinkerton seems even more at arm’s length. Cio-Cio San rarely looks directly at Pinkerton, even when they have privacy from her family. Though it may be an accurate picture of how a geisha and an American stranger may interact, Cio-Cio San’s aloofness and evasion of eye contact felt entirely at odds with how she speaks to Pinkerton. The effect of their once-removed relationship certainly makes her faith in their marriage that much more frustrating, and it seems to vilify Pinkerton even more, putting him in the role of “taker”, rather than earning any sort of affectionate reciprocity from his new bride.

This production of Butterfly brought a new question to light, one that seems strange not to have asked ourselves before now. Why does Pinkerton return to Japan, and with his new wife? Cio-Cio San reveals to Sharpless (and the audience) that she has a son by Pinkerton, but only minutes before the American ship arrives in the harbour - not enough time for Pinkerton to have heard about the child and travel to collect him. But there’s that fleeting moment in Act II (hours before Pinkerton arrives back at the house), when Goro says to both Sharpless and Prince Yamadori that Pinkerton’s ship has already been spotted.

Likely scenario: Goro wrote to Pinkerton, and told him of Cio-Cio San’s son. Sharpless likely already knows too, and he tries to tell her what’s about to happen in that painful letter scene. It’s tricky to know what to do with this extra layer of the story, since there’s little in the libretto and music to really demonstrate these details to an audience. The letter scene, for instance, still carries weight when we think Sharpless is simply trying to tell Cio-Cio San that Pinkerton isn’t coming back for her. But the betrayal of information about her son does add one more nail in Cio-Cio San’s coffin; so many people are making decisions for her, and everyone thinks they’re doing good (even though they’re not).

It’s always strange to see the selective sympathy that Puccini has for the characters in his opera. It’s clear that he knows Pinkerton ruins Cio-Cio San’s life, so he’s not an indiscriminate sadist; he gives a slimy personality to Goro, the man who sells women and who earns bonuses by telling his clients about the children they left behind, so Puccini is not necessarily in favour of tourism marriages like the one Pinkerton buys. And to be fair, it’s not Puccini’s job to insert lines of text into the story, like a line for Sharpless that would read something like, “Pinkerton, instead of taking the kid back home and ruining Cio-Cio San’s life, you could apologise, send them money regularly, and let them try and move on.”

Yet there’s something horridly patronising about how Puccini romanticises the Japanese. The music he writes for Cio-Cio San’s family at the wedding is purposefully cacophonous, almost laughable sound effects and definitely not the reactions of fully-realised human beings. The story of Madama Butterfly existed before Puccini’s opera, but there’s a clear attraction to her youth and ignorance, and the idea of “rescuing” her from her “shameful” past as a geisha and making her a proud Westerner, as though in recovery from her savage Eastern upbringing.

The more we see Butterfly, the more it seems like a window into Puccini’s life; that may be inaccurate and unfair, but the dead composer is a decent outlet for the rage that inevitably hits us by the end of Act III. Just like the most hateful villains of film and television, it takes an excellent performance to bring out this kind of reaction, angry as it may be; Leiser and Caurier’s production is distilled in the right way, exposing the story for all its highs and lows. Our only real gripe: that the production isn’t brave enough to let us sit and watch, in real time, how Cio-Cio San, Suzuki, and Sorrow wait silently between Acts II and III. The scrim that broke the timeline robbed us of the sense of anticipation and disappointment that Cio-Cio San herself feels.

The performance we saw was the same one that was broadcast in cinemas, which is hopefully what accounts for the weird lighting bloopers that gave momentary distraction. Also, perhaps some cinema goers can vouch for being shown something more interesting during the Interlude than a bland blue screen.

Madama Butterfly runs at the Royal Opera House until April 25. For details and tickets, click here.

Comments