Schoenberg in Hollywood & a heap of excess

ReviewThe question of how to express one’s identity in music is one of the music world’s most pervasive questions for all people who partake in music as an art form. For nobody was this more true than Arnold Schoenberg, a singular figure in music whose own personal crises between himself and the world around him eventually led to a revolution that completely changed the face of Western concert music, for better and worse.

Thus, an opera about Schoenberg’s life is certainly logical endpoint, considering that Schoenberg’s crises included everything from an unfaithful wife and disparagement of his music by critics to World War I and the rise of Nazi Germany.

What is also, perhaps, a rather sensible entryway into this is to reframe Schoenberg’s life according to the conventions of varying film genres: this is exactly what composer Tod Machover and librettist Simon Robson’s new opera Schoenberg in Hollywood has opted to do. The “Hollywood” of the title is a metaphorical Hollywood that exists across multiple genres of film, which change according to the needs of the drama. On a certain level, this conceit makes a strange amount of metatheatrical sense: it is highly esoteric, complex music filtered through a popular medium, and in theory it is the perfect frame for depicting a man and his circumstances in a way that amplifies the theme of how the man relates to his increasingly complex circumstances.

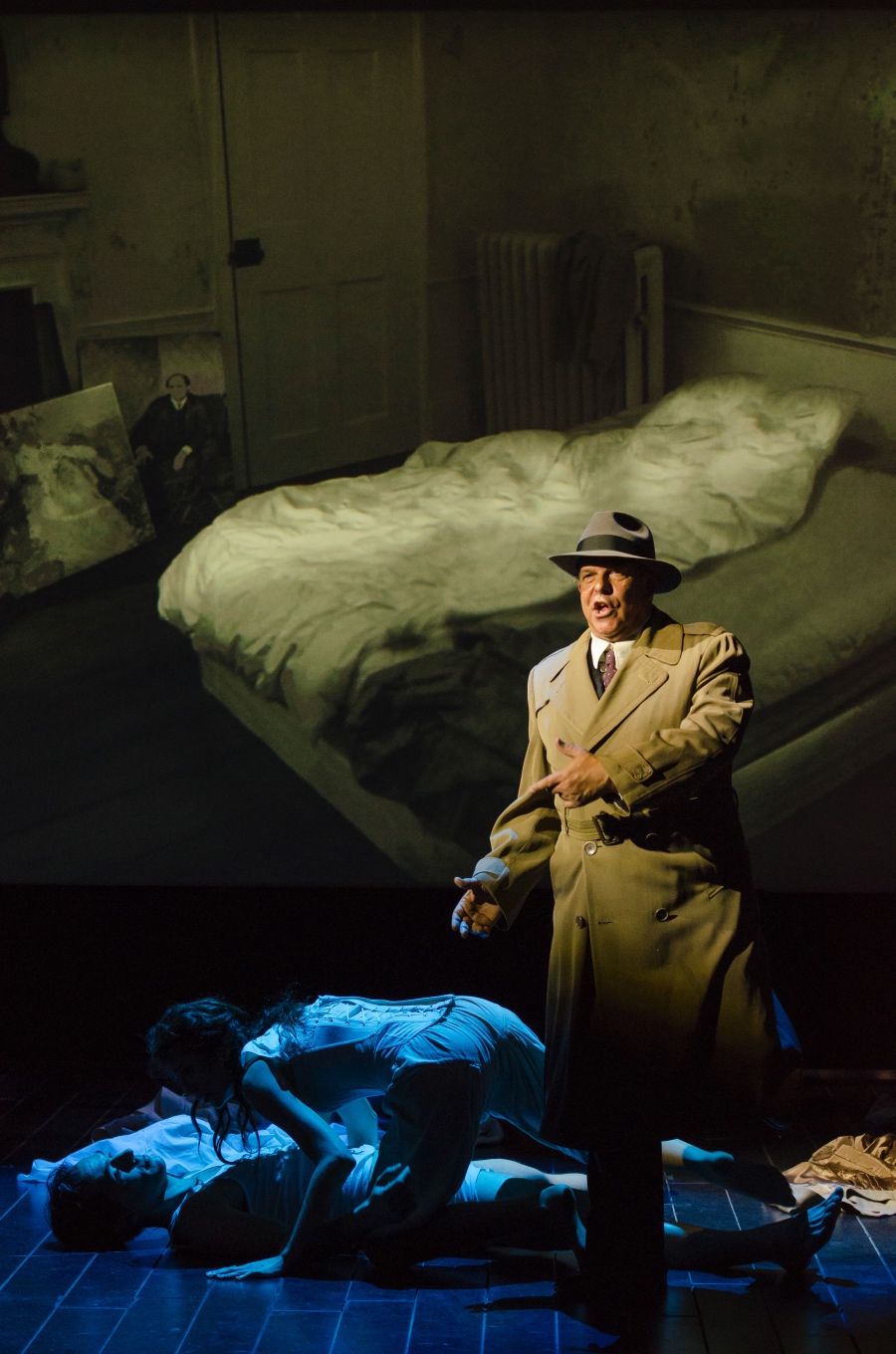

Alas, if only the final product understood the virtues of restraint! Its frequent dips into genre-based excess often veered into garish, meandering displays that more often than not proved so distracting it lost sight of the work’s soul. There is, for instance, the portion of the opera in which Mathilde Schoenberg’s infidelity is framed in an imitation of film noir.

There is something incredibly weird and unsettling about Arnold Schoenberg losing his German accent to the rhythms and accent of Humphrey Bogart, and considering that Schoenberg forgives Mathilde and her lover anyhow the choice of film genre came off as insincere. If it was not that, it was also incredibly on the nose: framing Schoenberg’s journey to Los Angeles as if Schoenberg had taken Montgomery Clift’s place in Red River seemed obvious in the most absurd way, and it should say something that Schoenberg being dressed in a cowboy hat with twin holsters for revolvers is somehow the least gaudy part of that scene. And then there was “Superjew”, a reference to the superhero genre that was so misguided that came from so far out of nowhere I could only react to it by digging my face as deep into my palm as I could.

Only occasionally does this amount of excess work to the opera’s advantage. There is a segment that details an anti-Semitic episode around a lake that is treated very much in the style of a Marx Brothers skit, and while it does get deeply uncomfortable I think playing the scene without the Marx Brothers’ brand of exaggeration would’ve dulled the impact of this moment. The immediate segment that follows takes a Looney Tunes approach to the rise of the Nazi party in Germany, and there it took the subversive nature of the Marx Brothers skit and played into it even further. Unfortunately, neither moment really managed to land in large part because the utter insanity that surrounds those moments takes their punch away.

The excesses frequently distract and get in the way even when the work does remember its soul. Perhaps a perfect microcosm of this problem occurs in a scene in which the reactions by Schoenberg’s critics are juxtaposed against the adulation of such figures as Alban Berg and Gustav Mahler. Here, the idea of juxtaposing the two is actually executed rather well, as Berg, Webern, and Mahler are all incredibly lyrical in their praise for Schoenberg, and it is juxtaposed in a really good way against Mathilde quick, snippy reading of his critics. But juxtaposing both against Schoenberg singing something along the lines of “I’m killing tonal keys” to the tune of “Singing in the Rain” was so on the nose it was groanworthy, and to the degree that it almost sucked out whatever interesting thematic purpose the scene set up.

Only a few scenes survived unscathed, and it was in these moments where the excess was completely absent that the opera truly found its voice. The scene in which Schoenberg witnesses the death of his first wife Mathilde and also sees the first World War does a rather excellent job of giving some insight into his reasoning for jumping fully into twelve-tone serialism, for instance, and the use of Pierrot Lunaire quotations to highlight the preceding argument between Mathilde and Arnold was incredibly dramatic. There’s also a recurring thread about Moses und Aron that offers a perfect jumping-off point for the dialogue of commercial viability versus speaking to one’s true soul. Unfortunately, these moments are few and far between, and they too get swallowed up by the excesses.

The worst part is, on the surface this is not a bad idea. As mentioned in the program notes and by Robson in the talkback that followed the performance, the original idea was much more naturalistic, with very early versions detailing Schoenberg’s actual life in Hollywood. In my estimation, their initial idea would likely have led to a dramatically inert work that had nothing to say. I have said plenty about this work already, but one thing I cannot call it is dramatically inert, and this concept actually does have something to say about an artist’s place in the world. If it had reigned in the excesses, the result could have been an earth-shattering masterpiece. What we get is only middling, and it is really such a shame because the Schoenberg fanboy in me really wanted to like this work.

It is also a shame, considering that Machover’s score is generally quite excellent: his score is incredibly rich and so full of character that I genuinely think it does warrant a second listening. Moreover, it manages to toe the fine line between fidelity to Schoenberg’s style and having its own dramatic identity with an insane Berio-esque touch that keeps each moment feeling new and refreshing, whether it quotes Bach or Ravel or even Schoenberg himself or it spins off into its own thing. Machover has called himself a big Schoenberg fan (he was conceiving the work for twenty years), and this is certainly reflected in the attention to detail in his score.

I also cannot fault the three singers that ran around the stage of the Emerson Paramount Center for anything: Omar Ebrahim somehow managed to create a great evocation of Schoenberg and a compelling character while navigating the work’s frequent excesses, and Sara Womble and Jesse Darden both deserve all of the accolades they will no doubt get for playing a variety of characters ranging from both of Schoenberg’s wives to The Good Earth producer Irving Thalberg and back. All of their voices were also top-notch, with Ebrahim’s stern yet warm voice soaring across Machover’s frequently difficult vocal writing, and with all three projecting excellently over the ensemble.

But at the end of the day, a part of me cannot get over the excesses of following each film genre’s conventions. The conceit certainly could have worked with the right amount of restraint, but the problems with the show’s tone are so plentiful they took over the entire evening. Perhaps with a few tweaks in the libretto and less excessive production design, this opera could have become a masterpiece. It is a shame, then, that it falls short of its goal in the ways that it does: as a fan of Schoenberg myself, I was really hoping the show would be what it set out to be.

Boston Lyric Opera’s world premiere production of Schoenberg in Hollywood runs through November 18. For details and tickets, click here.

Comments