Schoenberg/Bach & other unlikely pairs: AtG Theatre heads to TIFF

InterviewThe Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) is best known for its star-studded galas and premieres that take over the city every September; yet it actually does some amazing programming all year round. They present both classic works and those that may be relatively unknown to those who are not serious cinephiles.

One of these amazing programmes is the upcoming retrospective on Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Not Reconciled, which runs at their flagship location the TIFF Bell Lightbox from March 3rd to April 2nd; TIFF will present a collection of 16 feature films and 26 short films by the duo. Curated by James Quandt, senior programmer at TIFF Cinematheque, the retrospective will feature their work in all of its poignant clarity.

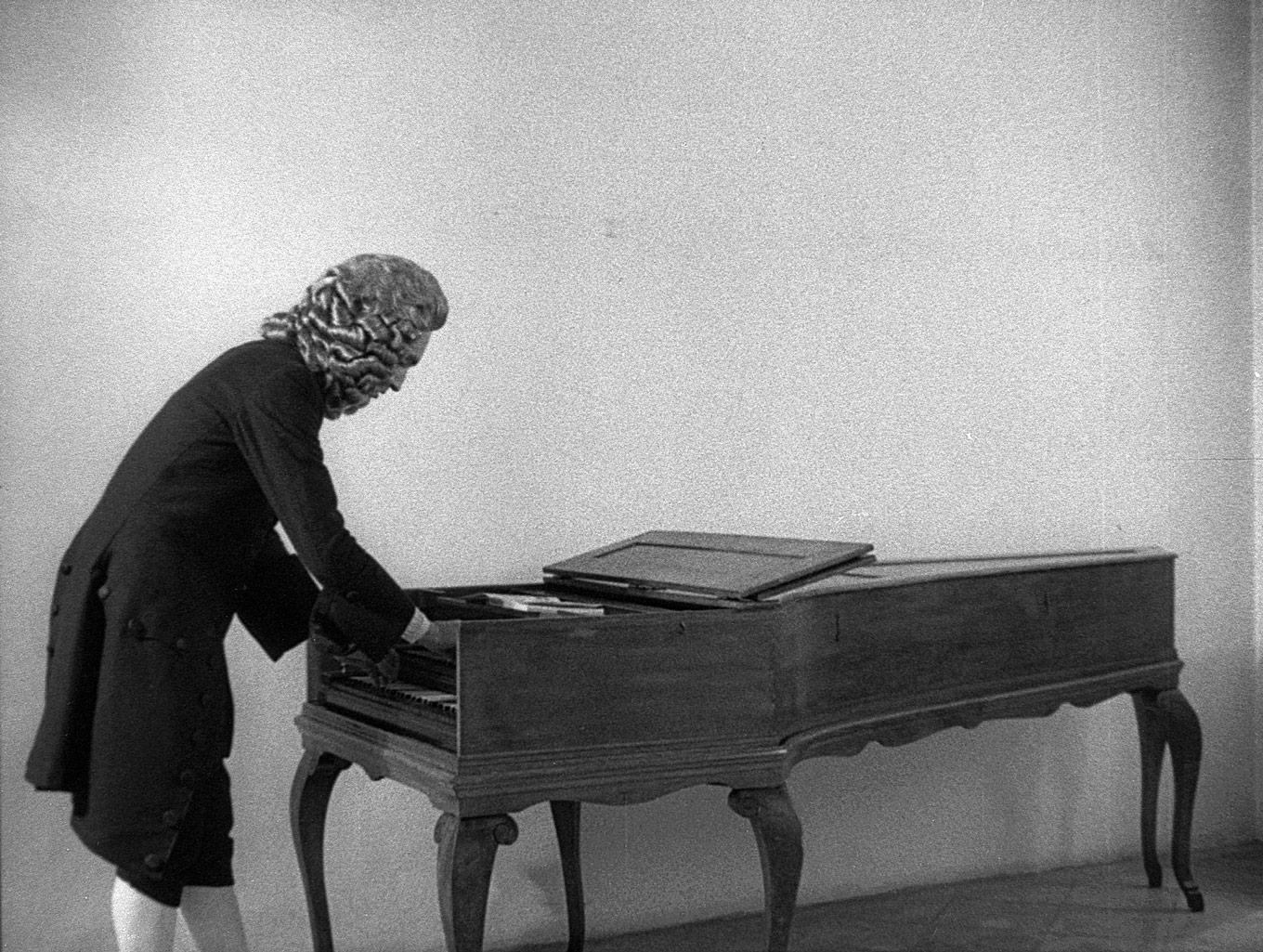

Not Reconciled opens with a screening of a new 35mm print of The Chronicles of Anna Magdalena Bach, and tells the story of her last several decades alongside her husband, the remarkable Johann Sebastian Bach. Interestingly enough, it also will show a double-bill of the pair’s odes to Arnold Schoenberg (yes, that Schoenberg) by presenting Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s “Accompaniment to the Cinematographic Scene” on March 3, and Moses and Aaron on March 12.

The showing on March 12 will be accompanied by a live performance of some of Schoenberg’s music by Toronto’s star indie opera company, Against the Grain Theatre, featuring soprano Adanya Dunn and AtG Music Director Topher Mokrzewski on piano.

I caught up via email with both James Quandt from TIFF and AtG’s Artistic Director Joel Ivany to talk about the retrospective and the relationship between film and music - in particular when talking about Straub-Huillet.

How did you first find out about the films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet?

James Quandt: Their films have long been “legendary in their absence,” i.e., famous despite being largely unavailable (at least in Canada). I often wonder at the paradox that their work has exerted such a profound influence on contemporary cinema, given its relative obscurity, but European cinematheques have presented many retrospectives. My own first encounter was with their early short The Bridegroom, the Comedienne, and the Pimp, which I saw on a holiday in New York four decades ago, when one still had to travel to see films!

How did Against The Grain become involved with this TIFF Retrospective?

Joel Ivany: Against the Grain Theatre is always looking to collaborate with the best cultural institutions in Toronto and beyond. Our Editorial and Digital Media Manager, Amanda Hadi, also works as a Digital Engagement Producer at TIFF. Once she heard about the Straub-Huillet series, she thought a live performance from Against the Grain Theatre (AtG) would be a great complement to a screening (I kind of totally agree). The staff and programming team were luckily already familiar with AtG and they immediately went about to make it happen.

In your role of Senior Programmer at TIFF Cinematheque, how would you describe your priorities in your selection of programming, and what does the programming process look like in general?

Quandt: The duty of my vocation is to present the breadth and scope of international cinema, from the silent period to the present, so that cinematheque-goers can, over time, be acquainted with the most important lineaments of film history. However, I make no secret of the fact that another very strong priority is showing films that I love and/or want to see myself, in hope that many others will feel the same way.

How familiar are you with Straub-Huillet’s work?

Ivany: Well, when presented with the partnership, we (Topher and I) immediately went online and found as many clips as we could to see what we were getting into.

What has been fascinating to learn about the husband-wife filmmaker duo is the way that they use space. They would often make art in public spaces, like the Place de la Bastille, without any artifice, and in one long take.

This is exactly how AtG came to be: we started the company with the aim to find new spaces for opera that directly enhance with the piece and enhance the experience for the audience, pulling them into a pure musical experience. We were especially floored to learn about Straub-Huillet’s “direct sound” approach: they would film scenes without any post-production dubbing, with the sound captured live on site — and the takes often picked up extraneous noise from the outdoor spaces where they were filming. That is as pure to a live operatic or concert performance as you can get. (And pretty similar to why we find it exciting to perform live music in bars, like our monthly Opera Pubs.) So although I haven’t seen the full-length films, I’m looking forward to discovering their work during the series.

Outside of the programming for this retrospective, what are your experiences with both Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach as well as Arnold Schoenberg?

Quandt: One of the great passions in my life is classical music, and both Bach and Schoenberg are among my favourite composer. I have countless CDs of the cantatas, Brandenburgs, Passions, orchestral suites, concerti, and the solo keyboard music, on piano and harpsichord. (Mahan Esfahani’s recent disc of the Goldbergs is staggering!) For Schoenberg, I love the string quartets, the violin concerto, Pierrot Lunaire, and the orchestral pieces. And, of course, the two operas that Straub-Huillet made films of.

Do you find there is much correlation between the works of J.S. Bach and Arnold Schoenberg? How would you approach their differences?

Ivany: I don’t really think you can compare them in the same vein. It’s like going to the National Gallery in London and then strolling over to the Tate Modern. Bach and Schoenberg are both composers of the highest quality, but should be viewed (and heard) differently. Context is such an important aspect for appreciating music. To understand what the limitations were and then seeing the freedom that came out of those limitations is what truly separates the good from the “we’re still talking about them in 2017.”

There will be a live performance of Schoenberg’s work presented by Against The Grain Theatre. How did you hear about this opera company and why did TIFF reach out to them for their involvement?

Quandt: As an opera lover, I’ve been aware of the exciting work that Against the Grain Theatre has been doing for some time. Considering that they are known for presenting fresh, daring re-interpretations of classical repertoire with scaled-back accompaniment to bring out the full force of operatic singing in close quarters, we readily decided to invite them them to perform before Straub-Huillet’s radical versions of Schoenberg’s operas as a perfect complement. I hope both film and opera lovers will turn out for this special event on March 12.

In what ways (if any) has Straub-Huillet’s work inspired your own work as a director?

Ivany: From my very minimal exposure to their work, I am immediately drawn to their individualistic approach to cinema: I read that their art was “born of resistance… to the conventional movies they were forced to study at school.” (Cool right?)

I’m also inspired by their insistence that their films were meant to be immersive, not illusionistic. They wanted their audience to lose themselves in their films.

Straub-Huillet didn’t make their art, in their minds, for any kind of elite — they thought the average person would appreciate films on Mozart, Schoenberg, Cezanne, Kafka… This is how I look at my own practice. I’m drawn to the stories and art I’m drawn to, and I know I can find a way to present it that won’t alienate audiences but make them stumble on a new discovery. I honestly try to put myself in both the most jaded patron and also the newcomer. What will open their eyes and what will make them come back?

What questions do you hope that Toronto audiences will ask and/or answer upon seeing any of the films in this retrospective?

Quandt: Straub-Huillet’s films are fiercely political and the issues they raise are ever more current, given the dark times we are living through. I hope the films help to illuminate the history that has led us to this perilous moment. Machorka-Muff, for example, tells us a great deal about the persistence of fascism in Europe.

How do you see Against The Grain’s participation enhancing the experience for TIFF’s audience?

Ivany: We hope our performance helps illustrate some of the principles Straub-Huillet were trying to execute: immediate, direct sound captured in unusual spaces in an egalitarian manner. And our performance will work as a brief introduction to Schoenberg’s music, his methods and 12-tone theory, which will hopefully complement the film screening of Moses and Aaron.

This past week, we were able to have an open, pop-up rehearsal in the atrium of TIFF Bell Lightbox. To see a new and engaged audience stop by and listen to both pianist Topher Mokrzewski and soprano Adanya Dunn rehearse is what makes this collaboration so special. It’s been really great to work with a partner that is open to creating intersectional performances like this, who wants to activate their building into a site for film, art, and music.

Describe your own personal relationship to music in film.

Quandt: I largely follow the edict of Robert Bresson, the French director (and mentor of Straub!) who after using Mozart, Bach, and Schubert in his films to sublime effect, then completely rejected the use of what is known as non-diegetic music; i.,e, music for which no source (radio, player, etc.) is apparent. Too much traditional music is used cheaply in film to manipulate or emphasize emotion.

If you could direct a film version of any opera, which would it be and why?

Ivany: I’d love to turn any of the AtG Mozarts we’ve done (Figaro’s Wedding, #UncleJohn or A Little Too Cozy) into a film. They’re almost like watching TV. The English libretto makes it easy to follow and the music drives all the action forward.

What can you say about Straub and Huillet, for any of our readers who may be hearing Straub and Huillet’s names for the first time?

Quandt: Again following Bresson, Straub-Huillet were determined to employ the purest possible means to “awaken” eyes and ears deadened by conventional cinema. They did so in a number of ways - through abrupt and surprising edits, anachronism (mixing historical periods both within the frame and within the film), the use of direct sound, natural light, and historically charged settings. (It often turns out that sunny pastoral locales have been the sites of historical trauma, for instance.)

In your expert opinion, what would you say makes their films so controversial?

Quandt: Their expectation of an audience schooled in music, painting, philosophy, history, politics. And on the latter note, their often polemical stances on political issues. All of which I find bracing and invigorating.

What are three movies you couldn’t live without?

Ivany: Well, currently they are: Children of Men, Braveheart, and Bullets Over Broadway (in any order).

Quandt: Alain Resnais’ Muriel … Robert Bresson’s L’Argent … Roberto Rossellini’s The Rise to Power of Louis XIV.

What movie is your guilty pleasure?

Ivany: Rocky.

Quandt: None of my pleasures are guilty.

The retrospective Not Reconciled runs from March 3 to April 2 at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in downtown Toronto. You can find more information and purchase tickets here.

Comments