Simulacrum: Futuristic angst and dance

ReviewThe word simulacrum, is having quite a run these days. Rooted in Latin, it has been used at least twice in the last two years, first as the title of a ballet and currently as that of an opera, the inaugural project of Path New Music, that played earlier this month for three performances at the 3LD Art and Technology Center in New York’s financial district. The meaning of simulacrum ranges from a likeness and similarity to an unreal or vague semblance.

The ballet, presented by the Norwegian National Ballet in 2016 brought a young Argentinean ballet dancer together with a 77-year-old Japanese flamenco master in a program that fused kabuki with flamenco and dance with theater. Video segments indicate that via role reversals the work pondered cultures, identity, and the cycle of life. The ballet resides in the former definition of simulacrum.

The opera, about a young dancer who loses her leg and has a conflicted relationship with its bionic replacement and also her partner in dancing and life, appears to occupy the latter. Broadly interpreted and playing to the opera’s self styled emphasis on technology, Simulacrum is about the conflict between human and machine. More specifically, it is a story of futuristic angst told against a backdrop of techno-existentialism.

Path New Music describes itself as an upstart artist collective of composures, musicians, choreographers, and visual artists. Five Path members, Longfei Li, Yangzhi Ma, Peter Kramer, Meng Wang and James Diaz jointly composed the evocative score. Reiko Futing, billed in press material as musical supervisor and guest composer, wrote an alluring and atmospheric prelude and an equally compelling epilogue. The taut, non-linear libretto by Marianna Staroselsky, based on her play, would be fascinating as spoken word without music and holds the opera together.

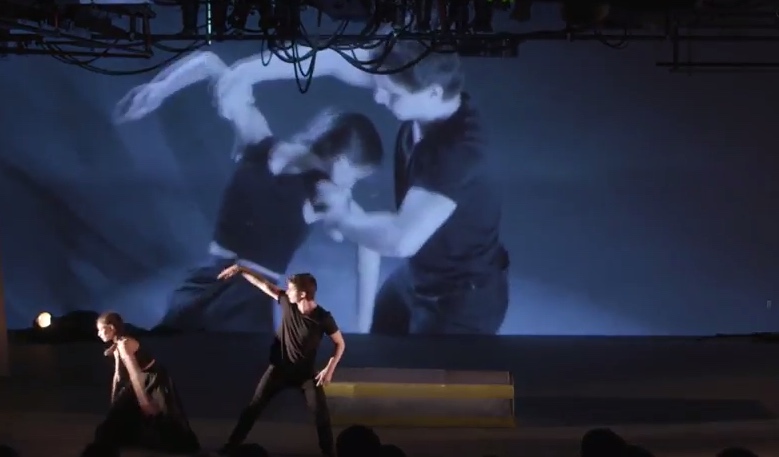

As is sometimes the case with works that wear their technological prowess on their sleeve, the most effective elements were not technological. There were five dancers, oddly costumed, but sharp and vivid from their initial entrance in which they portrayed pedestrian traffic encroaching on Lydia, the dancer who lost her leg. Evita Zacharioglou’s aggressive and insistent choreography along with Kyle Soble’s astute lighting created most of the evening’s technological tumult. Individual LED lights were briefly worn while Lydia’s bionic leg and Elias’s shirt intermittently blinked.

The space at 3LD, a raw box with exposed hardware, is the quintessential avant-garde environment. The room was dressed up with side curtains of opaque plastic strips, reminiscent of those used to conserve the refrigeration of meat and fish in supermarkets. Singers and dancers darted about against large screen projections of Lydia and her partner, Elias, both looking like advertisements for a high-end skincare product.

The projections achieved a vaguely Blade Runner effect with large and generally placid images of these otherwise frenetic and troubled souls. At times the side curtains silhouetted Elias and Stump, a human manifestation of what is left of Lydia’s leg, turning them into old-school shadow puppets until they dramatically burst through into the every-changing reality of the piece. At this point it is useful to mention that baritone, Nathaniel Sullivan sang Elias and also played Lydia’s bionic leg. Stump, was sung by soprano, Nina Dante.

The music, a cacophony of isolated instruments, vocal sounds and undulating rhythms, appeared seamless as it moved from one composer to another. Longefei Li’s throbbing music following the prelude was an effectively forceful representation of Lydia’s reaction to her surgery. Yangzhi Ma’s tense and hallucinatory composition chronicled the ensuing despair.

Having established its atonal disposition, the opera finds plaintive romance in the shapely minimalism of Peter Kramer’s music that relies predominately on flickering violin and ominous piano for an interlude and the scene following. Kramer sketches a musical space, coloring it with instrumentation expressing dramatic yearning and tension. In sync with Staroselsky’s libretto, he creates moments of tenderness in this otherwise chilly work.

The opera takes a melodic turn with Meng Wang’s scene in which Lydia and Elias hope her bionic leg would make both of them whole again. Wang mingles baroque tinged phrases with amorphous cosmic rhythms maintaining the distinction of each in a grippingly harmoniously manner. This was in captivating contrast to what had preceded and would follow. It clearly underlined the dilemma of human vs. machine.

Dancer, Dante J. Norris joined Zacharioglou in duets that created an alternative language for the opera. Clad for their numbers in dark attire rather than the curious metallic leotards and fluff worn at points by the ensemble, they danced in their own time and space to the angrily churning music of James Diaz. The music grows both turbulent and despondent as the scene progresses. At one point, live and on screen, they were performing two different dances depicting Lydia’s intense experiences. It was an involving and oddly satisfying moment in which, like Lydia and Elias, one strained to comprehend the whole.

With the exception of Futing’s prelude, the score was recorded and played back to accompany the singers. The voices and music were mixed to produce a hyper and unnatural sound. Michael Raymond Massoud was the conductor. Kexin Li’s performance of the prelude on the vibraphone was an event in itself. The brief work is spacious and ethereal. In retrospect it was a subtle and organic expression of the clamor to come. Li used a variety of implements to strike, caress, and otherwise coax the vibraphone with lovely control and elegance. The performance had begun as we observed this graceful musician.

Opera singers are required to be more than singing actors these days. The degree of physical agility is increasing to the point that dance and movement, not to mention general fitness, must play an increasing role in their training. The three singers here were ready for the challenges and appeared to relish them.

Mezzo-soprano, Lucy Dhegrae as Lydia was grimly emotional. Forceful, resigned, rhapsodic and angry, she kept up with the opera’s fierce pacing and was convincingly agile in her response to the Arthur Makaryan’s abstract, grinding and highly charged direction. Dhegrae displayed impressive vocal control in a variety of challenging physical positions.

Much the same can be said for Sullivan who handled the staccato vocal effects and obsessive gestures with impressive strength and precision. Sullivan’s pivoting from Elias to bionic leg was so credible, that it compensated for the distracting obviousness of his flashing Flash Gordon inspired costume.

Nina Dante sang Stump with plenty of anger and fury. If there was, by design, a glacial distance between the audience and Lydia and Elias, Dante’s Stump zoomed in and stayed there.

Perhaps Simulacrum communicates more readily at the Norwegian National Ballet than it does with Path New Music. There was a sense in the ballet selections that a definition of the word, indeed the concept, emerged simply by watching it, not via lengthy program notes, as was the case at 3LD. In lieu of such rhetoric, this Simulacrum would have been better served with subtle visual delineation of its prelude, scenes, interludes and epilogue. In fact, the hour-long work is rather over-burdened with these dividers but with six composers and an abstract story, some clarification is needed.

From the start, when the tones of the vibraphone enveloped the audience, we were held in rapt attention. Then the opera began, proceeding without intermission, to forge a powerful definition on its own. Futing’s epilogue, by the way, is courtly and yearning, at times wistful and almost jaunty but not to the extent that it alters Simulacrum’s somber ambiguity.

Comments