Smetana's Dalibor gets reality show treatment at Oper Frankfurt

ReviewA new production of Bedřich Smetana’s Dalibor premiered recently at Oper Frankfurt.

Smetana, known by North American audiences for his opera The Bartered Bride, is the composer most responsible for the formation of a Czech national musical identity. With Dalibor – a 15th-century knight who faces his feudal overlord despite certain doom –Smetana created a symbolic, revolutionary figure for Czechs of the late 19th century, who were resisting Austrian oppression.

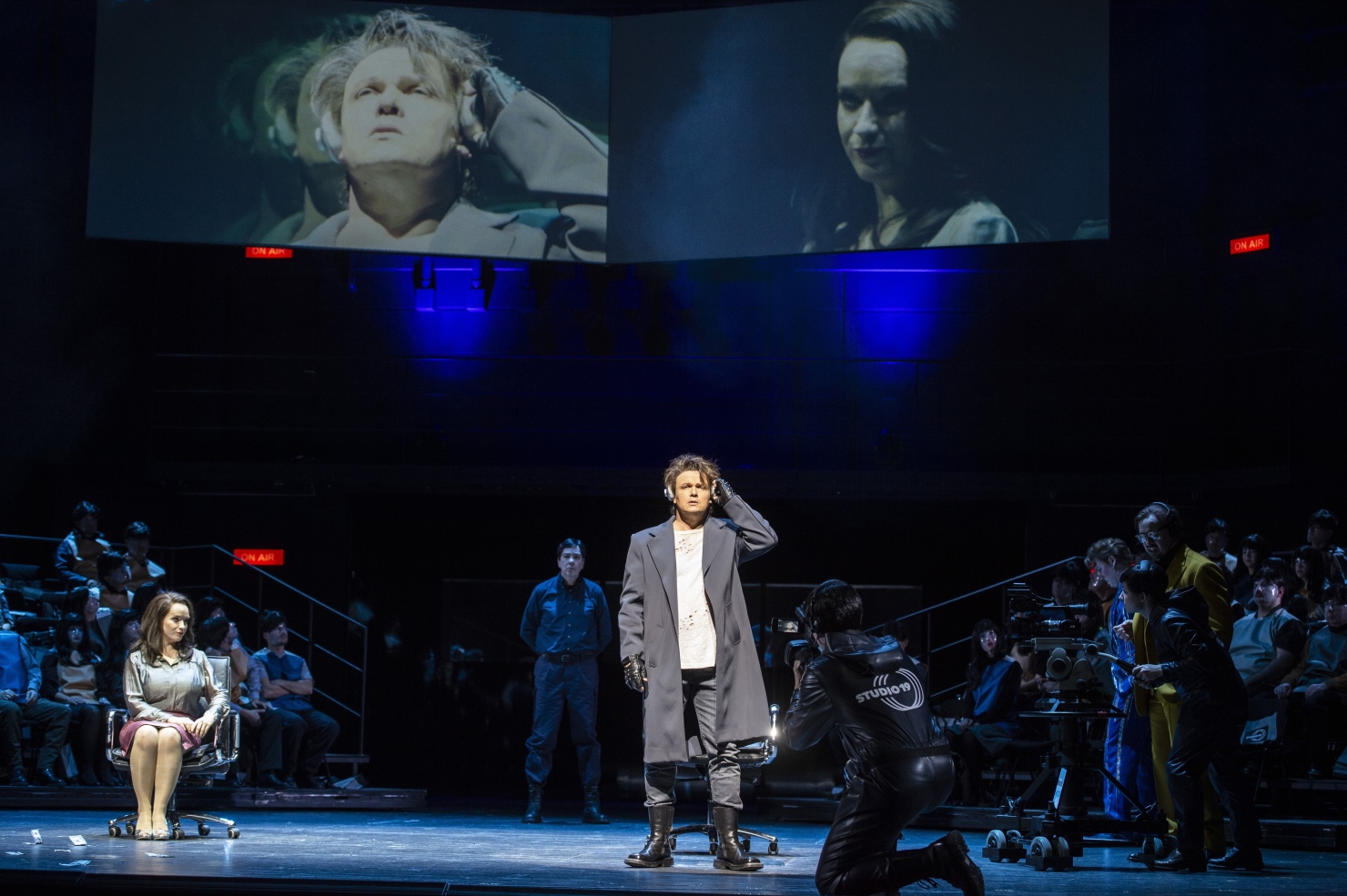

Director Florentine Klepper moves the opera’s action, which begins with Dalibor’s trial, to a modern television sound stage, where a live Dateline-style reality show is taping. The program’s narrative is constructed from carefully monitored, highly produced confessionals. Applause signs and sensational graphics provoke tailored reactions from the studio audience, which itself seems on the show’s payroll.

Dalibor is guilty of murder and doesn’t argue otherwise. Particularly damning is eye-witness testimony from the victim’s sister, Milada, paired with TMZ-like footage of the murder in progress.

He testifies instead that he killed to avenge the mysterious murder of his best friend. A clip shows a shrouded man handing Dalibor his friend’s severed head in a box. (The rubber-looking head drew chuckles from the opera audience.)

Dalibor’s defense flops with the TV audience. He’s sentenced to life, confined in the network’s basement holding cell. (There’s an unintended verisimilitude here: on Project Runway for example, after a contestant is kicked off, she can’t go home until filming wraps.) The twist in Dalibor’s fate is that Milada, upon seeing Dalibor’s impassioned speech, falls madly in love with him and vows to free him.

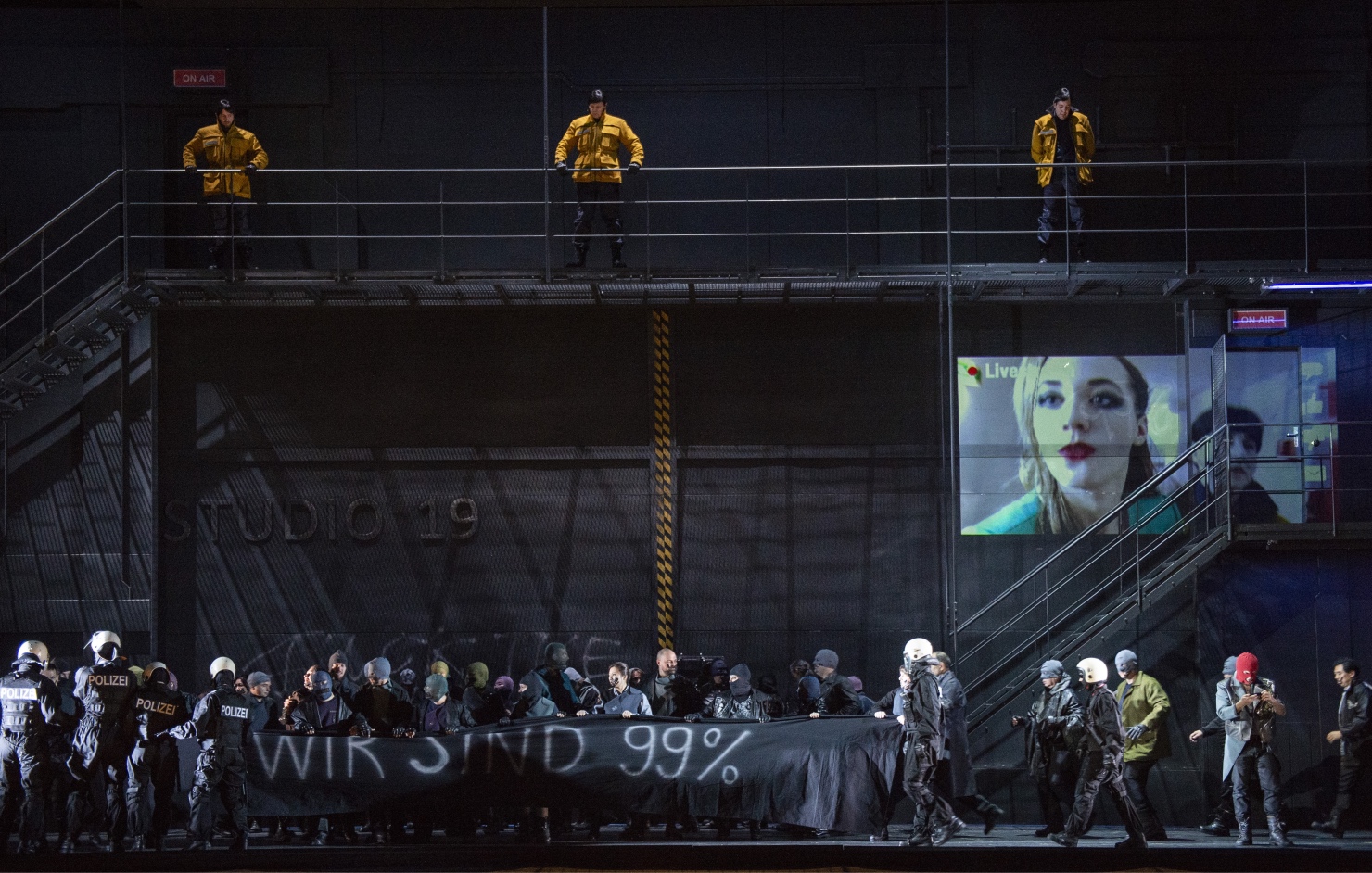

Outside the studio, a ragtag group of punky protesters await the trial’s verdict. They graffiti “fuck the system” on the studio wall and later hold “We are the 99%” signs,” but for what exactly they advocate is unclear. Are they anti-corporate greed Occupiers or run-of-the-mill anarchists?

Logistics are murky across the production, particularly regarding the television studio. Why does it have access to an untried murderer and who gave it the judicial authority to carry out sentencing? Has low-budget reality TV taken over government?

It’s hard to tell who or what is being satirized here.

The general critique could be that media is manipulative and reality TV in particular – though this show is closer to America’s Most Wanted than The Apprentice – is influencing politics by degrading citizens’ moral values and buoying charlatans into positions of influence.

Or maybe the production decries the symbiosis of partisan media and national political institutions, though the program isn’t as focused or insidious as say, Fox News or Infowars.

But these readings require stretches of the imagination beyond what the production provides. The satire, positing an unrecognizable villain, is indecipherable and toothless, rendering the drama superficial.

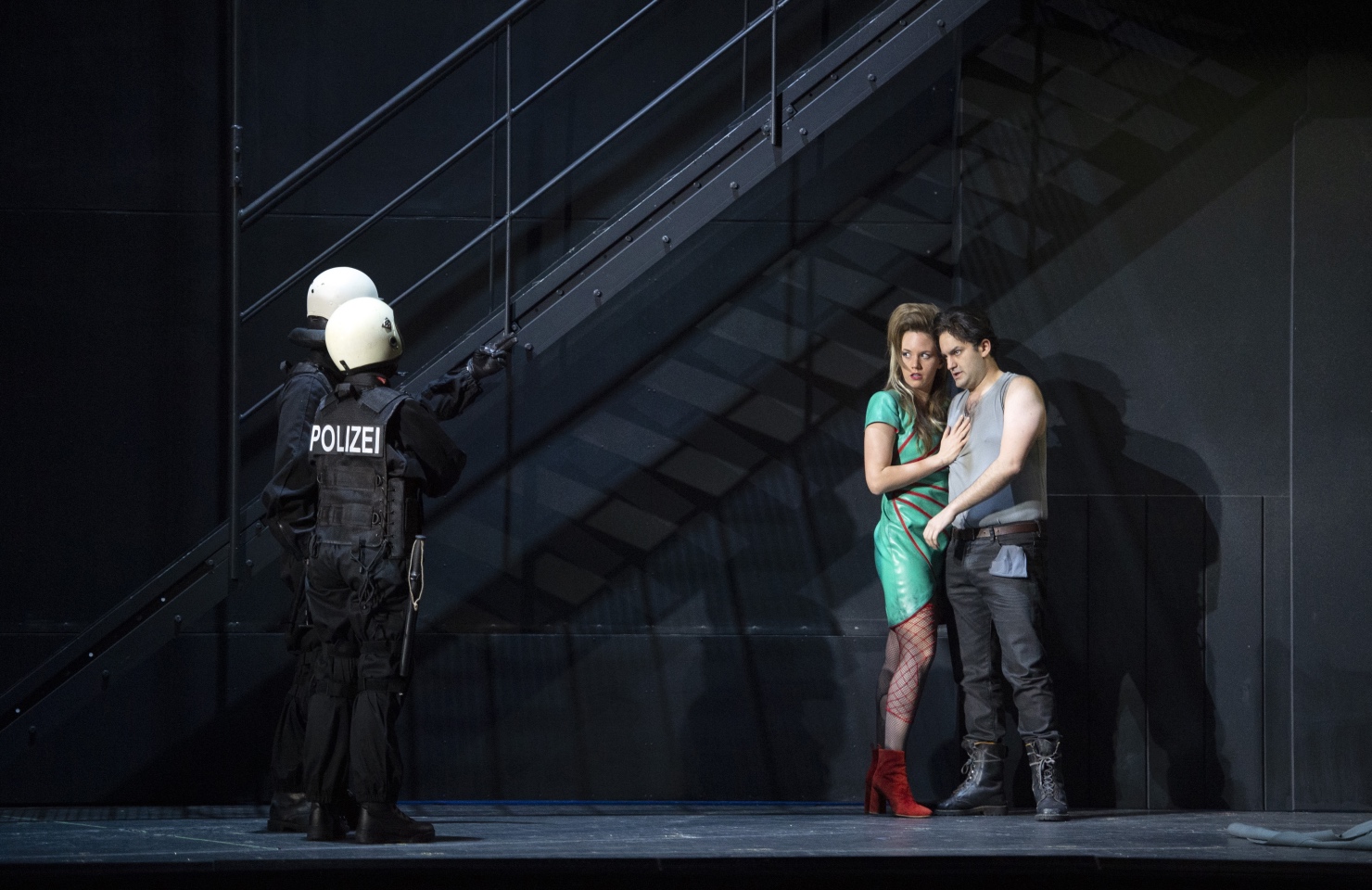

Moreover Dalibor, rather than die a hero of the disenfranchised, winds up a common criminal. On the verge of escape (Milada dresses up Fidelio-style to get in with the guards and slip Dalibor prison-breaking tools) Dalibor strategically places a bundle of dynamite under the studio audience bleachers. He successfully blows up the studio before being apprehended by authorities; an act that seems more like domestic terrorism than heroism.

Klepper wonders, in her show notes, how meeting violence with violence functions in our increasingly nationalistic political landscape. A good question, though the conclusion the production raises is banal: violence is bad because people get hurt and both sides are to blame. Shoving Dalibor into a context in which his motives are more personal than patriotic degrades the stakes of a vulnerable nation defending itself against legitimately oppressive occupying forces and flattens what can be a stirring drama.

The bright spot in the production, as is often the case at Oper Frankfurt, is the capable cast of singers.

Bass Thomas Faulkner’s voice, burnished with blooming upper and lower ranges, lends the duped guard Beneš heartfelt warmth and sympathetic loneliness.

Angela Vallone (Jitka) has a bright, youthful timbre tinted with ruby undertones. The role hops her through the bulk of her range, which includes a surprisingly resonant chest voice.

Theo Lebow, who typically sings character tenor roles, is mismatched as Jitka’s boyfriend Vítek. Nonetheless he holds his own in the supporting role.

Tenor Aleš Briscein likely interprets the title role more fluidly in his native Czech. His German sometimes suffers from overly blended consonant clusters that elide words and syllables into smooth but unintelligible combinations of sounds. His singing, initially plagued by imprecise intonation, settled down and remained fresh throughout the evening.

Izabela Matuła’s (Milada) vocalism was effortless and rich, though not hair raising.

Gordon Bintner’s (Vladislav) singing is refined, fluid, and technically sound. He marks moments of heightened expression with straight tone punches that can seem more intellectually planned than spontaneously felt.

Maestro Stefan Soltesz balanced the orchestra’s volume well to the singers’ voices. Unfortunately, Smetana’s idiosyncratic dances, which are the score’s hallmark, never grooved under his baton.

Like the production, the audience had little to say. Their lukewarm ovation, including boos and half-hearted responsory bravos for the production staff, suited the evening’s shrugging aspect.

Comments