Surreal, Devastating Journeys Through Nighttown

ReviewAs an opera critic, one of my favorite things to experience live is opera written within the last ten years or so: it is always interesting to see new opera make its way in the world, and even more so to see what composers are making up. Invariably, there are works that run the gamut of “serviceable but could use some tweaks” to “this is a great opera”, but rarely do I ever get the sense that there is a work that is an instant classic of the repertory. I do not exaggerate when I say this, nor do I choose my words lightly: there is a new operatic classic in town, and it is young composer Benjamin Perry Wenzelberg’s Nighttown.

Nighttown is billed by premiering company Lowell House Opera as a reimagining of James Joyce’s Ulysses: it takes Molly Bloom’s 36-page soliloquy from the end of the novel and bases its run time on that, and on extracts from Chapter 15 earlier in the book: it uses both to explore themes of lust, death, extramarital affairs, and what home actually feels like. One might ask oneself how on Earth one goes about adapting the work of a writer whose prose is as dense and frequently impenetrable as James Joyce’s can be; fortunately, Wenzelberg found a way, and it is a direction that works to Nighttown’s advantage.

Essentially, how he plays with Joyce’s text is he uses Molly Bloom’s soliloquy as a device to frame and comment on the action that happens on-stage; this is established quite early on in the show, in a moment when Molly sings out “piano” and the orchestra suddenly quiets down, as if Molly has smashed the fourth wall for a single second. From here, the action plays out in a surreal, dream-like manner: events happen out of chronological order, character arcs overlap in layers, the tone frequently shifts from comedic to serious and then back again at the snap of a finger, and some events are displayed as a direct response to other events that happen mere minutes before. The libretto, while often not a literal representation of what James Joyce does with language in his work, nevertheless plays with Joyce’s methods by leaning into the fact that Joyce’s work is always some form of stream-of-consciousness, and he thus opts to go for an emotional stream rather than a language stream.

That ultimately works in the show’s favor: as Mahler proved so often in his symphonies, emotional stream of consciousness tends to translate very well into music, and this is something that the music of Nighttown demonstrates in practically every way imaginable. There are so many dramatic textures achieved throughout the whole musically, and each one matched each scene beautifully, from the crunchier bass textures of an implied BDSM cuckolding session in the second act to the warm, inviting harmonies that accompany the finale where Molly and Leopold Bloom seem to come to an understanding about their marriage, and how it has been affected by both their infidelities.

It also does something exceedingly rare, which is that it shows Wenzelberg is a highly original composer: about the closest I could come to describing his music is as a blend of Berio and Mahler, and even that comparison does not feel quite correct in spirit. Wenzelberg describes his language as twelve-tone melodic lines situated within a largely tonal environment; I am not sure if that accurately describes his music, as in my estimation it is probably the work that best toes the line between conventional and unconventional tonal harmony, as even when his harmonies are conventionally tonal the ways he arrives at them or leaves them are super unconventional. But what is more, each transition into and out of these harmonies feels completely seamless, and even at its most tonal it never feels trite, either. Harmonically speaking, this is a musical language that, try as I might, I cannot really connect to anyone, except in the parts where he is intentionally drawing an allusion to different music.

It is a gift in other ways as well. The orchestration uses multiple unconventional instruments including electric guitar and several uses of whirly tubes, but none of the bizarre, unusual orchestrational touches felt gimmicky like orchestrations using such things so often do, and the colors Wenzelberg wrings from even the more conventional parts of his fourteen-piece chamber ensemble are daring even if they sometimes are inadvisably thick. His vocal lines, while often daunting and wild, never feel like they are difficult to sing, and even in several spots where my composer instincts were saying they were a caution spot I marvelled at how it felt like the singers were set up beautifully. It also plays with quotation in a truly spectacular way: “Lá ci darem la mano” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni makes frequent appearances, but Wenzelberg goes further than to just play it as is: he instead makes the materials of the duet a character of its own, throwing either just the harmonies or just the melody at various instances in the story, and even making a motif from that duet a recurring musical and emotional leitmotif.

“I think this opera has an immense future in the opera house.”

I could spend all night talking about how Wenzelberg’s music is a treat all on its own, but all you really need to know is that, even if it does not set Joyce literally, it honors the spirit of what Joyce’s prose does, and I for one cannot wait for a second listen to let all the music’s complexities wash over me. This is some highly original music, and I cannot recommend listening to it enough.

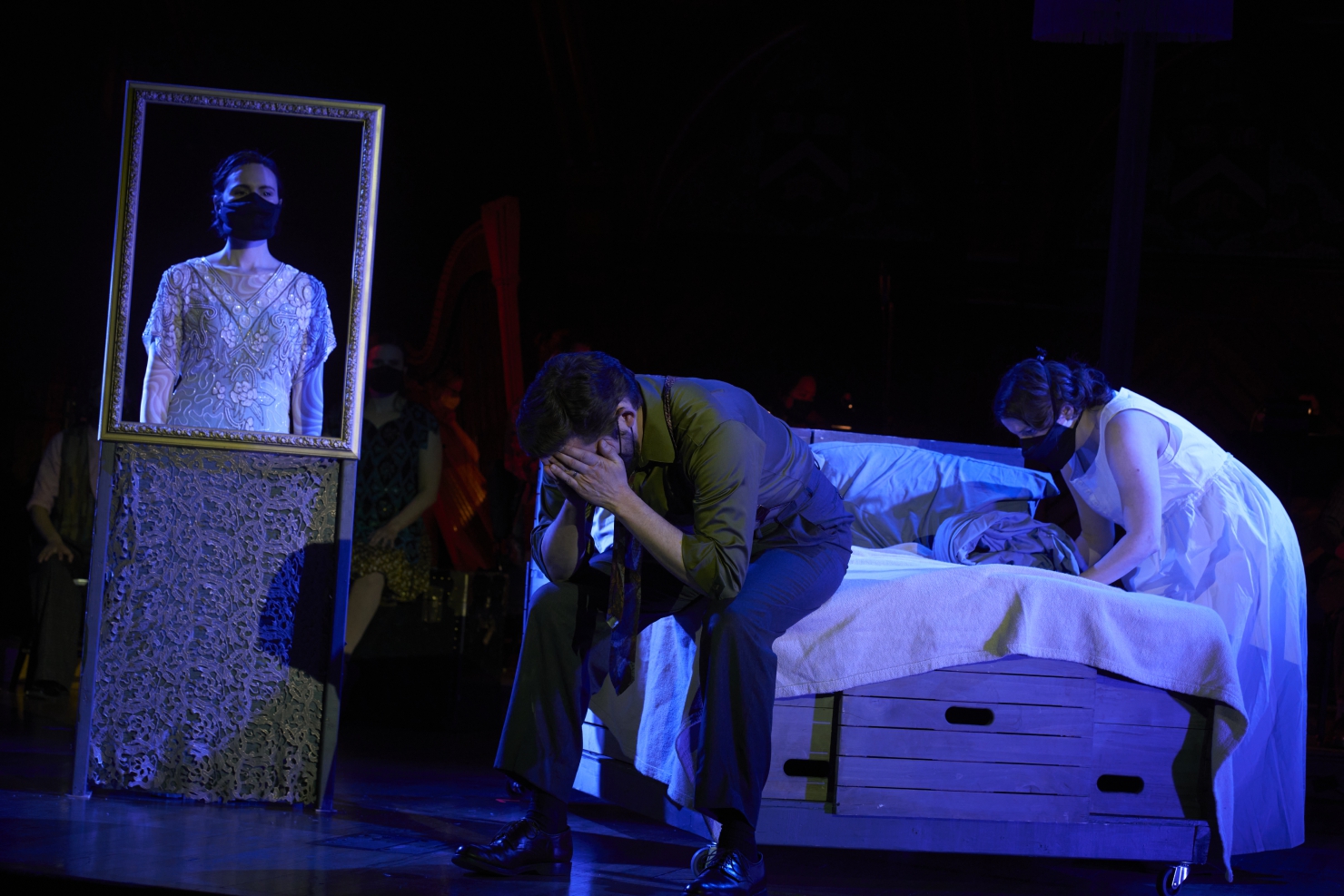

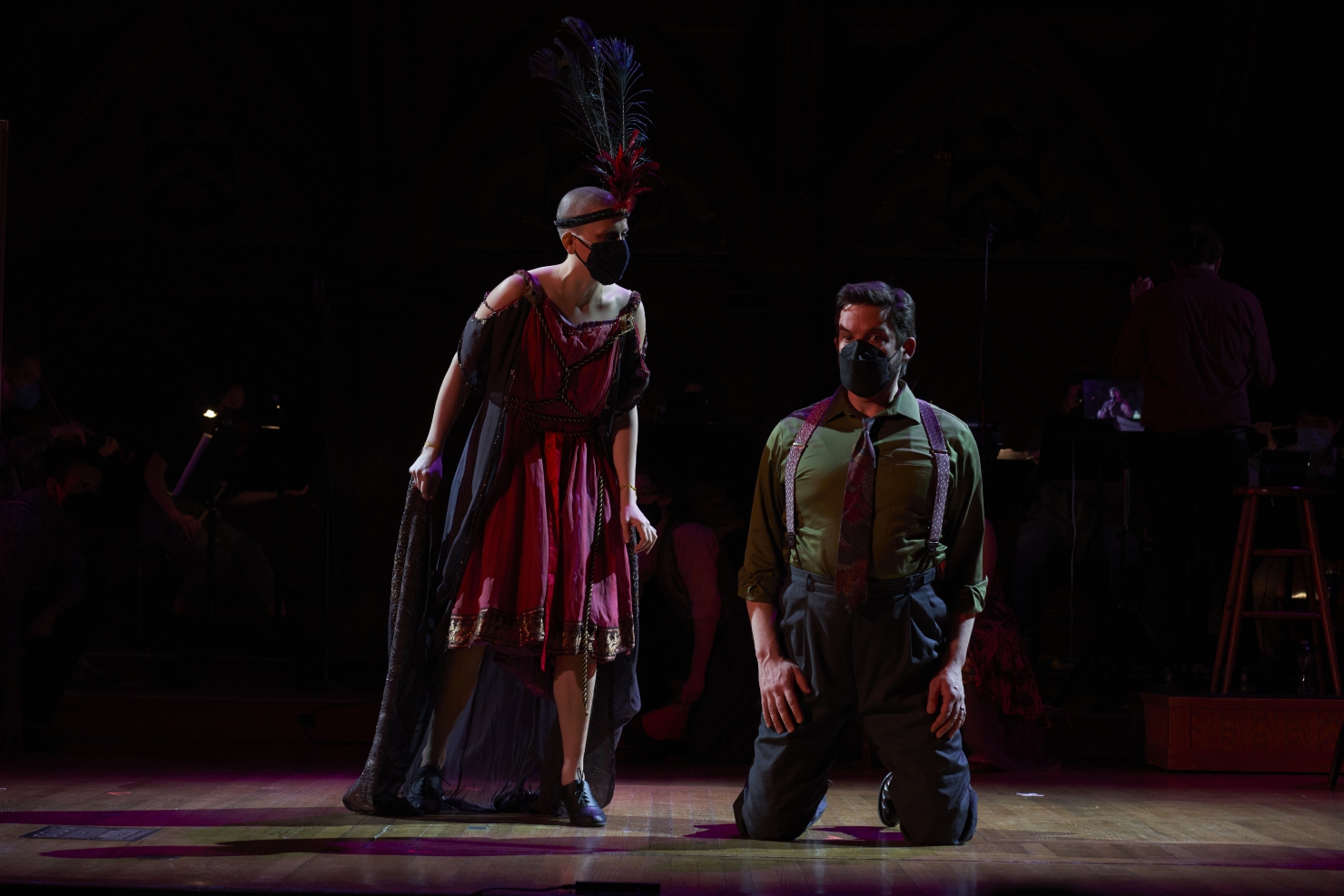

It should go without saying that music like this requires a rather daring cast, and this cast tackles the challenges of the music head-on. Caroline Olsen made for a strong emotional anchor to the show in Molly Bloom, and while I felt her voice could sometimes be a little soft for the part she navigated the show’s many insane stream of consciousness tracks with ease. David McFerrin was every part her equal as Poldy Bloom, stirring up the persona of someone who was fairly pathetic but also incredibly complex at the same time. And then there’s Erin Merceruio’s Nymph, who springs from a painting at the top of act one: it was a role that got more demanding with time and requires her to almost be multiple people at once, but Erin managed these turns wonderfully. Other stand-outs in the cast include Elijah McCormack’s Bell Cohen, Arhan Kumar’s Stephen, and Alex Chen’s Blazes Boylan. While Mr. McCormack’s voice felt a little soft to my ear, he nevertheless brought an intense energy to Bell that electrified his gender-bending cuckolding scene with McFerrin in the second act. Arhan Kumar made for one of the most interesting characters of the night: he managed shifts between his philosopher persona and the grief he felt at his mother’s passing with serious acting chops, and he accompanied this with a rather strident voice that told volumes. And Alex Chen? Mr. Chen really does not show up for very long in the show, but he stole practically every scene he was in with a milky, creamy voice.

“It is almost infuriating that something could be so good.”

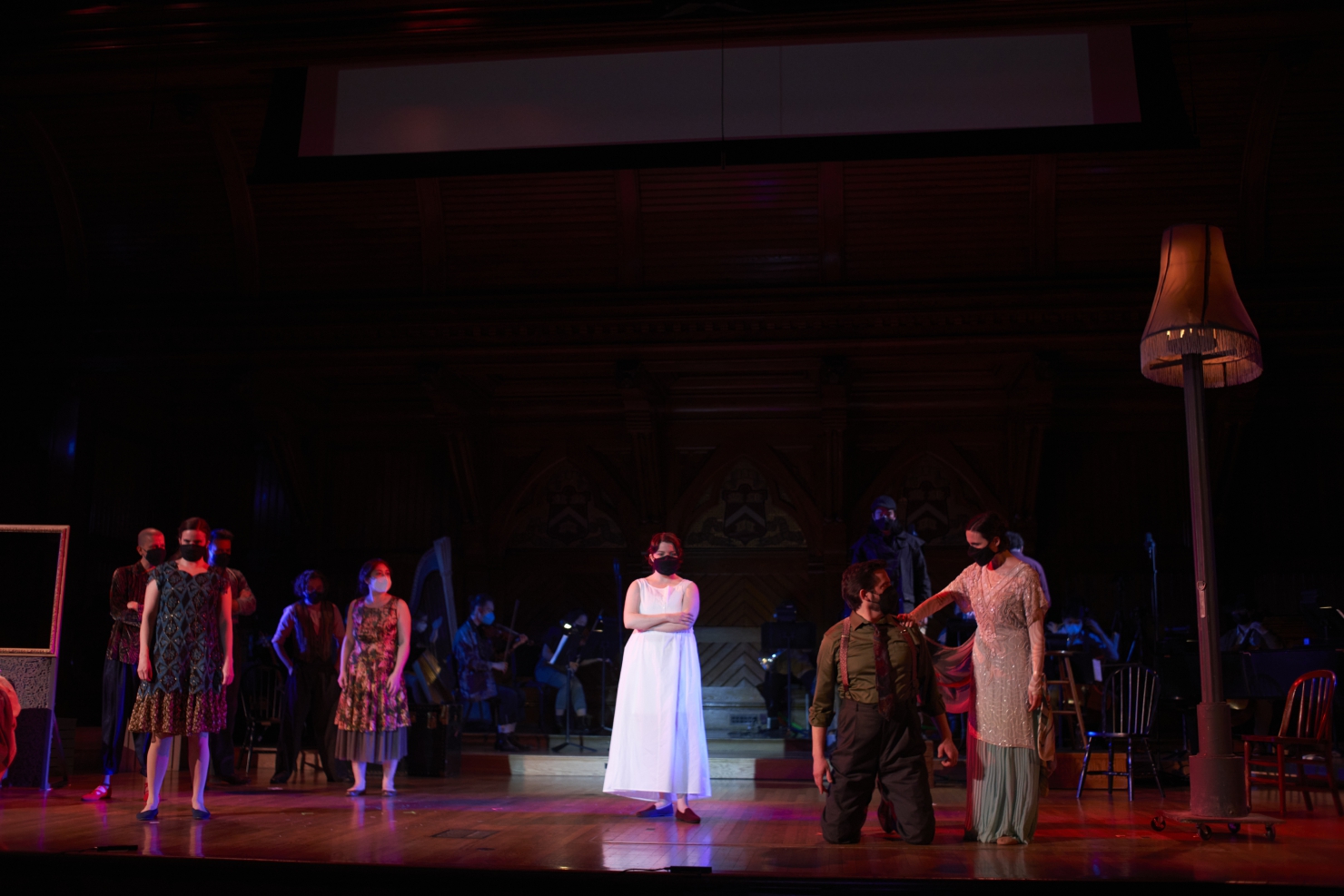

As for the production itself: as befits a small opera company’s return to live performance, the staging by director Adrienne Boris was quite simple, with only a bed, a standee that suggested a painting frame, and chairs as the only pieces of set. But with something so surreal as this opera, I am not sure that making that work with more pieces in the set would be successful without a multi-million dollar budget, and the lack of setpieces actually helped keep the music flowing at a good pace. There was some iffy work with the lighting of Sanders Theatre’s stage, but it was at the very least competent, and it never completely broke the show for me.

In fact, everything about this performance was one of those performances that was so strong that it is almost infuriating that something could be so good. The cast? Excellent. The production? It does show its budgetary restraints, but it serviced the performance super well. But most of all, Nighttown is just an all-around masterpiece. I struggle to come up with the right words to describe how brilliant I think Nighttown is, and I struggled with this even after I had just finished watching the show. All I can say, is that I think this opera has an immense future in the opera house, and I cannot wait to see the life it is no doubt going to take.

Comments