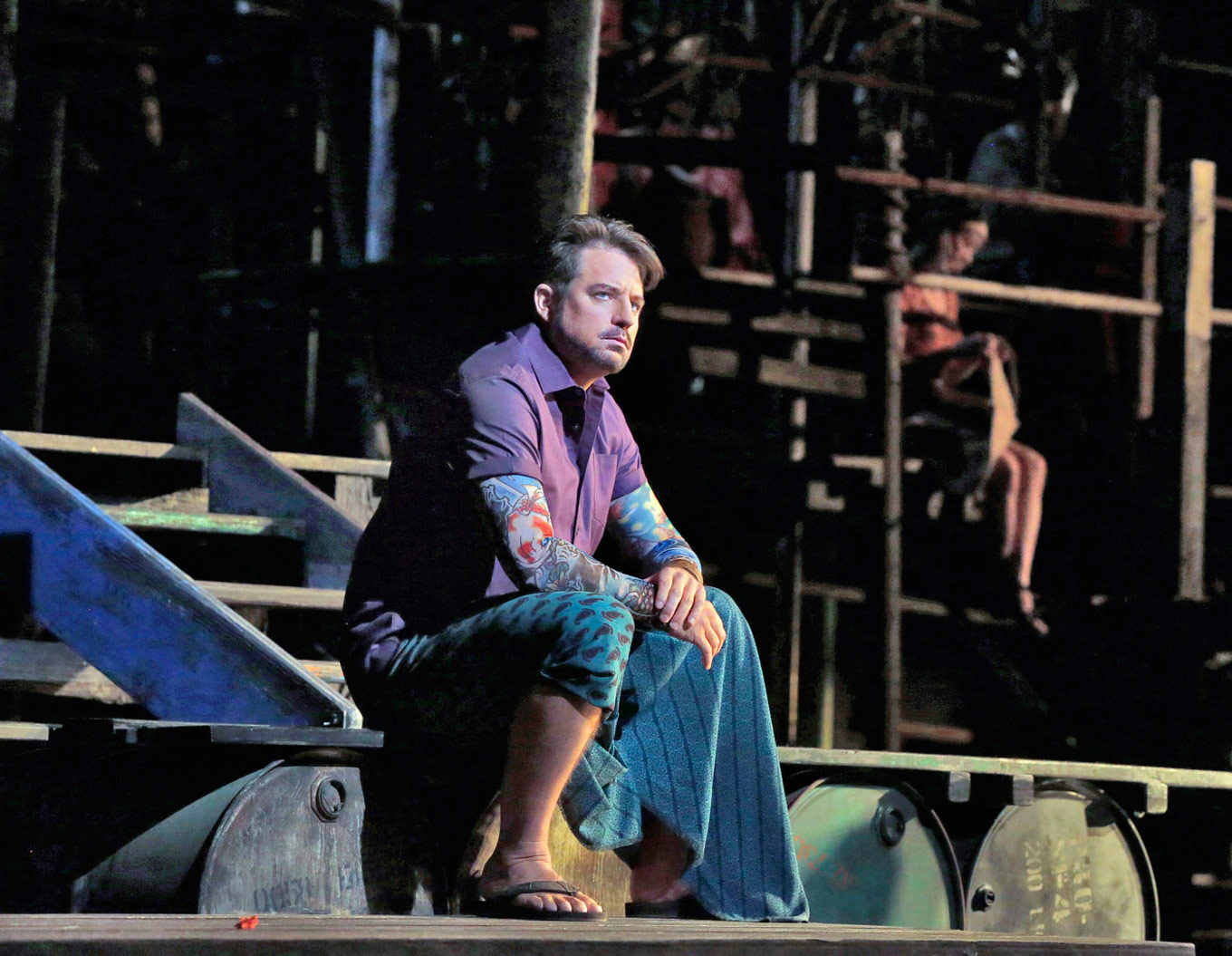

Talking with singers: Matthew Polenzani

InterviewFreshly off an acclaimed run as the title role in Mozart’s Idomeneo at the Metropolitan Opera, star tenor Matthew Polenzani has little time to come down before diving into two more productions in New York. “I think there’s a sequence where I have a show on a Friday, a show on a Saturday, then the Met Gala which is on Sunday. So that’s going to be a little tiring,” he says, clearly happy in his busy schedule at one of the world’s top houses.

Between performances as Idomeneo, Polenzani began rehearsals for Der Rosenkavalier, where he sings the (much higher) role of the Italian Singer, opening April 13; running nearly concurrently will be his role as Don Ottavio in the Met’s Don Giovanni, which opens less than two weeks later. “These kinds of things, they don’t come up very often,” says Polenzani of his neatly stacked season of varied performances. The tenor, who is nominated for a 2017 International Opera Award in the Male Singer category, offers up not just quantity, but thoughtful and inspired quality onstage.

“That’s as individual as a fingerprint.”

Though he has the calm, kind temperament that helps to keep nerves in check, the trick to maintaining a busy calendar is no mystery. “My personal feeling is that good vocal technique is the same in everybody,” says Polenzani. “But how you think about it, how you arrive there, how you determine it is for you, that’s as individual as a fingerprint.” He focuses on what he calls an “edgy, buzzy” sensation, which signals that his voice is projecting easily and healthily.

“The other thing that that [sensation] does, is when you’re singing all the time in that same spot, your legato is improved, dramatically.” Even after over two decades in the business, Polenzani still checks in with his teacher, with whom he has studied since 1998. “She talks to me all the time about keeping this sensation alive,” he says, adding that she still comes to hear him in rehearsal, especially in large spaces like the Met.

Polenzani points to the incredibly personal part of vocal technique as the main reason why singers can feel so exposed, even vulnerable onstage. “The worst part of being a singer is that the voice is inside the body,” he explains. “If you’re compromised in any way, the voice is going to be a place where you notice it.” Being compromised goes beyond things like congestion, allergies, and other illnesses that can trump even the best singing technique. “It’s hard to appreciate how hard it is to sing with life’s regular stresses on top of you.”

“If you’re going through a divorce, or there’s been a death in the family, or your children are misbehaving, or whatever it is, that stuff can be difficult on a voice.” Polenzani has watched his own colleagues go through tough times in their offstage lives, and the personal costs are certainly audible in a singer’s voice. “On the other hand, I also know singers who have been through divorce who are singing better afterwards, because the stress of a failing marriage was difficult on their voices.”

“We needed to start trying to figure out how to live.”

Polenzani knows very well the weight of life’s tragedies, and the ripple effect they can have on a career. “After our daughter died, I didn’t work for about 7 weeks,” he says of Alessandra, who passed away on December 24, 2005, at just 16 months of age. “Usually for us, it’s the month of her birthday, which is August, and the month of her death, which is December. It’s those weeks that lead up to those days which are especially hard.”

At the time, Polenzani was set to travel to Seattle, to start rehearsals for in Così fan tutte. The relationship that he and his wife, Rosa, had with Speight Jenkins, past General Director of Seattle Opera, was both professional and friendly; incredibly, Polenzani kept that contract, arriving somewhat late to the rehearsal process. “Rosa and I talked a lot about it, and in the end, in order to somehow start to feel like life is still going on, rather than stuck in the blackness we were stuck in, we needed to start trying to figure out how to live.”

“The worst part of it was, ‘Un aura amorosa’,” he says of his first performances after Alessandra’s death. Ferrando sings the aria about his beloved Dorabella, but for Polenzani, “it was always about the smell of Alessandra’s room.” When he sang the aria then, and in later productions of Così fan tutte, that was the memory he channeled most often, as difficult as it was. “Even right now, I can recall the exact smell that her room had.”

For both Polenzani and his wife, the work he did in Seattle “sort of opened the door to being able to try to keep going.” He and Rosa were rarely apart for the next several months, and by the end of November, they had welcomed their first son, Gianluca. “For me, I thought it was important for us not to pass Christmas without a baby in the house.”

“We both absolutely say that it was the right thing for us,” he says. “It reaffirmed our parenthood. It reaffirmed our identities as a mother and a father.”

“I’ve made it a point to be as nice to everybody in my business as I can.”

“I don’t know how badly my singing suffered in those months,” Polenzani admits. He remembers having little patience for petty, diva-like behaviour among his castmates, and understandably, he had moments where opera and singing seemed unimportant. Today, he is on the Board of Directors of the SUDC Foundation (Sudden Unexplained Death in Children), which offers support and compassion for affected parents.

It’s an inspiring thing to note that the famed tenor, a fixture at the Metropolitan Opera, still comes honestly by his reputation for being kind and warm with his colleagues and his audiences. “I’ve made it a point to be as nice to everybody in my business as I can,” he says. With his fans, he makes a point to take the time to sign autographs outside the stage door. “There’s more than a little part of me that just wants to go home,” he says honestly, but the Illinois native is sympathetic to devoted fans, particularly those who wait in the cold after his performances. “They just want to talk to me a little bit and have me sign their programme, and say that they met me.” He adds with a laugh, “which is odd, on its face, for me.”

“I’m totally aware that the day is coming when nobody will be waiting for me. I’ll walk out the door, and they’ll be waiting for the guy behind me. Why not give these people 5 minutes of joy right now? Seems like it’s not such a bad trade-off.”

The success of Polenzani’s career, beginning at the dearly missed New York City Opera, and spanning 20+ years, speaks for itself. “I love to sing. I do it because it’s something that I’m good at, and I pay my bills with it.” Still, he insists that his life as a husband and father not only comes first, but it helps him in his work onstage. “It helps me identify with the characters that I play. It helps me become a more complete human being.”

Simply put: “My identity as a father and as a husband is more important to me than my identity as a singer.”

“I do love to sing, and I like making great music with great colleagues,” he says. “I like being in front of an audience, and thinking to myself that at least, I’m perhaps distracting them from what’s going on in their lives.” Polenzani’s biggest thrill as a singer comes from the idea that he is giving joy to his listeners. “That appeals to me immensely, and it’s probably the biggest joy that I get from being a singer.”

“But that thing comes in behind my identity as a father, my identity as a husband, my identity as a family man. I can’t put anything in front of it.”

Matthew Polenzani sings next at the Metropolitan Opera in Der Rosenkavalier, starting April 13. For more, follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments