Talking with singers: Sir John Tomlinson

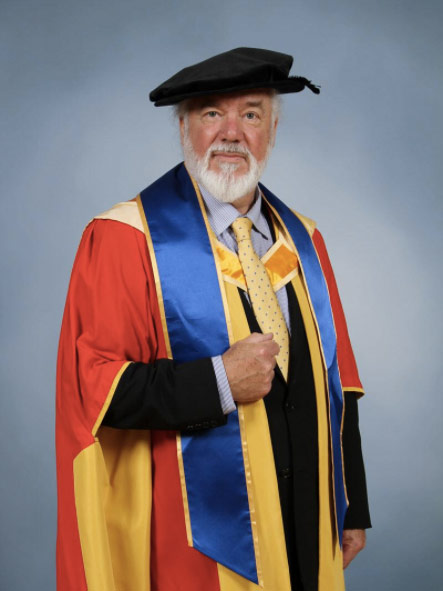

Interview“It feels quite good, actually,” laughs Sir John Tomlinson of his particularly honourable title, which he received when he was knighted in the 2005 Queen’s Birthday Honours list in recognition of his exception operatic career. “It’s a huge honour, and I’m still slightly bemused that I received it.”

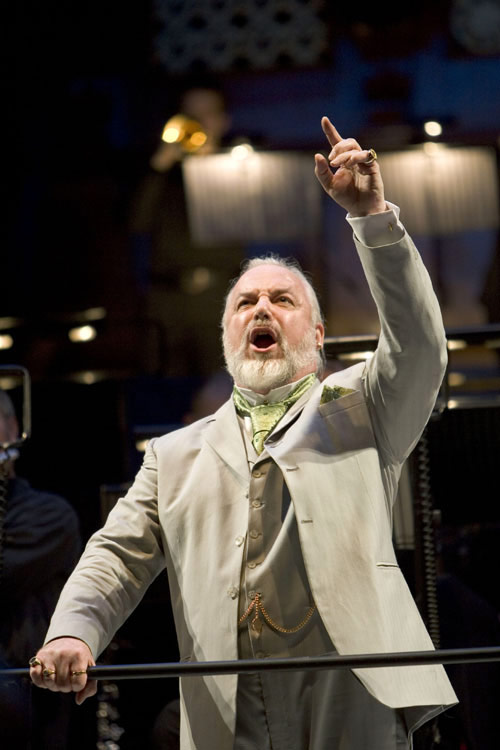

The Lancashire-born bass is preparing to sing in the much-anticipated UK premiere of Thomas Adès’ The Exterminating Angel at Covent Garden, and he’s currently earning guffaws with as the Sergeant of Police in English National Opera’s production of The Pirates of Penzance. In fact, the Sergeant of Police was Sir John’s very first operatic role, performed in 1966. “The Sergeant was ill, actually, and I stepped in,” he recalls, noting that the current ENO production is his first reprisal of the role. The “51-year gap” between performances is likely to be some sort of operatic record.

At 70, Sir John finds himself involved in plenty of contemporary opera. “I’m very much enjoying modern music at this particular phase of my life,” he says, inspired by the “newness” of works like The Exterminating Angel and Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur. “I really feel that it keeps me young, because it’s ever new.”

One of the few operas based on a film, The Exterminating Angel (April 24-May 8) demands much of its cast. “It’s a fascinating piece,” says Sir John. “It’s very unusual, in that there are about fourteen of us soloists, trapped in a room for the whole piece.” The cast stays onstage for the entire opera, meaning “in the course of a six-week rehearsal period, we’re rehearsing six hours a day, six days a week.”

“The whole of life’s experience is in those operas.”

He shows no signs of slowing down his singing career, yet Sir John is aware of what he can and cannot bring to the stage. “I think my voice is still fine, I sing well,” he says, agreeing with his contemporary audiences. He’s aware of a decline in energy as he grows older, and how “you get tired, your reserves are limited.”

“That’s why I don’t any longer do those massive roles, and I’m not invited to do them because I’m 70 years old, which is fair enough.” The “massive roles” Sir John is talking about largely come from what he calls “the very special decades” of the 1980s and 1990s, which he spent immersed in great Wagnerian roles like Hans Sachs (Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg), Wotan (Die Walküre, Das Rheingold), Wanderer (Siegfried), Gurnemanz (Parsifal), Hagen (Götterdämmerung), and the title role in The Flying Dutchman.

“They’re the most important years of my working life,” he says, proud of the legacy of live performances and recordings, particularly from his time at the Bayreuth Festival. There, in the late 1980s, Sir John sang his first Wotans, along with fellow first-timer Daniel Barenboim at the podium. In his 18 years at Bayreuth, he recalls, “I’ve never answered so much fan mail in my whole life.” The cast would sign autographs in the mornings following performances, “and it would be a two-hour long session with endless people.”

Though he broke up the Wagner years with other delicious roles like Baron Ochs (Der Rosenkavalier), John Claggart (Billy Budd) and Duke Bluebeard (Bluebeard’s Castle), Sir John remains “a devotee” of Wagner’s music.

“The Northern European mythology, I identify with. For me, it was part of my bones,” he explains. “[Wagner’s operas] express the human conditon, they express joy, and everything we’re terrified of. The whole of life’s experience is in those operas, in the most powerful way.”

Sir John’s journey to Wagner started by being “surrounded by amateur musicians” throughout his childhood and upbringing. He had family members who sang, played the piano and organ, conducted church choirs, and he even took some early voice lessons from his aunt. “I sang for all of my childhood years,” he recalls, later discovering the sheer size and power of his bass voice. “Everybody commented on it, said ‘my God, what a noise!’”

Sir John first pursued “a sensible course of study” as an engineer, before deciding to see where singing would lead. Clearly, it led to great things, even though he considers his proficiency with Wagnerian roles, even those with higher tessituras like Wotan and Sachs, “a surprise.”

“When it comes to managing a career, or decided to do Wagner parts,” he advises, “I would say to a young singer, trust your intuition as to which teacher is good, as to which repertoire feels good, and be flexible as to which direction you go.”

He never considered his career in terms of “destiny” or even a specific set of goals with Wagner roles at the pinnacle. “See where it goes. In my case, it led to very surprising places, which I wouldn’t have expected.”

“Your intuition is very, very important.”

Many singers approach their career with a series of checkpoints they hope to reach, yet Sir John believes instead in a broad range of options. “For a long career, I think you need to be stimulated artistically,” he says. “Include the whole gamut, don’t tie yourself down to one specific narrow area. That can stifle your creativity.”

He is aware of the ironic goals most singers pursue with their technical development. “We’re always aiming for a situation where an audience would say, ‘well, it’s obvious this person never had a singing lesson in their life, it’s so natural.’” In one sense, singing is a perfectly natural process, combining breath, muscular activity, and resonance, but it’s by no means simple. “You’re very dependent upon other people to say, ‘this is better than that’.” He adds that a singer is ultimately a steward of his or her own voice. “Your intuition is very, very important.”

“Even as a young singer, you have to be moving on, artistically and vocally,” says Sir John of the often too-safe approach taken by artists in their early careers. The practice room, he insists, is the place to be brave. “In a room without an audience, you can be quite ambitious, you can try all sorts of repertoire,” he says. “A 25 year-old baritone can work on Wotan’s Farewell, or Gurnewanz’s Narration.”

He is aware of the risks of “stretch repertoire”, but he’s equally wary of singers - and teachers - who avoid taking risk and potentially rob themselves of the rewards. There’s a huge difference, he says, between working in a practice room and taking an ambitious role out in public. “That’s pressure, that can be really hard to handle. But privately, you can push the Wotans, you can be quite ambitious.”

“Nothing must be overdone, but at the same time, you have to be always moving on. Playing safe and singing things which are absolutely in the middle of your range, which are not developing you at all, doesn’t get you anywere.”

“One has to talk it up, rather than talk it down.”

Sir John’s career, spanning nearly five decades of professional work, puts him in a prime position to observe the opera industry, and its place among contemporary culture. He was 10 years old when Elvis Presley appeared on the scene, kicking off a “massive cultural change” with the advent of commercialised pop music.

“Before that, there wasn’t ‘pop music,’” he says, referring instead to the “light music” that came out of musicals and songs by the likes of Ivor Novello and Irving Berlin. “Opera and classical music have suffered, because generations have grown up listening to pop music, and not listening to Mozart and Beethoven as much, if at all.”

On top of losing a generation’s exposure to classical music, perhaps pop music’s “invasion of the musical scene” has also led to the condemning of opera and opera companies, by both the media and by select artists from within the industry. Sir John sees this condemnation as an accelerant for the sorts of dire straits which seem to be constantly looming over today’s opera houses. “It just strikes me that sometimes we’re in danger of talking ourselves into a disaster.”

“The media seem to really have it in for opera, generally. They seem to love knocking it, because it’s a sort of exclusive art form.” When artists themselves lend their voices to the negativity, “I think that’s terribly, terribly destructive.”

A recent example comes in David Sanderson’s article for The Times, which featured criticism of the management at English National Opera. “A company like ENO needs support. There are lots of good people who care about that company,” says Sir John, acknowledging the company’s difficulties with a reduced budget. With insufficient help from organizations like the ACE, companies like ENO are understandably on the hunt for private sponsorship.

“So, one has to talk it up, rather than talk it down,” he reasons. Though there indeed exist problems within the industry, its champions have a responsibility to lead with the positive, especially considering most companies’ mission to attract new audiences and new supporters. “If you’re a potential donor thinking, ‘I love opera, I want to help an opera company,’ and then you read something in a newspaper where an artist or singer is slagging off a national opera company, you’re not going to support that company.”

“Sing beautifully, sing expressively, sing well.”

Sir John remains optimistically realistic about opera’s place in the 21st century. Though it will likely continue to be a minority among genres, “opera will always exist, I think.”

“We won’t have the vast volumes of pop music, of course, but so what? It will still be loved by millions of people. It will still have a wonderful contribution to make to humanity.”

Opera seems to have contributed happiness and purpose to Sir John’s life. He calls singing “a wonderful thing, a spiritual, uplifting thing”, and his identity as a singer is a true part of his person. “If I don’t sing for a day, there’s something not complete about the day.”

He started singing in a sort of “experimental” way, that experiment soon turning into a sense of duty, that perhaps he owed it to himself to pursue it seriously. “To be on the inside of these roles is an incredible experience.”

“That’s what I’ve done for the last 50 years,” he says, as though it were simple. “Sing beautifully, sing expressively, sing well, as nature intended.”

He adds with a laugh, “easier said than done.”

The entry date for the next intake for Rose Bruford College’s flexible online programme is January 2nd. For details, click here.

Comments