The evil banality of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk at Oper Frankfurt

ReviewParadoxically the most authoritarian rulers are usually the pettiest. After Joseph Stalin and his cronies attended a performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s wildly popular opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (currently at Oper Frankfurt in a new production by Anselm Weber), the dictator directed the creation of a now infamous critique in a 1936 issue of the Soviet magazine Pravda that lambasted, and implicitly threatened, Shostakovich and his two-year old work.

The bad-faith argument went that by rejecting clear, simple melodies in favor of cacophonous musical chaos, the composer distorted opera and “ignored the demand of Soviet Culture that all coarseness and savagery be abolished from every corner of Soviet life.” The opera was banned by the Soviets for nearly three decades.

Of course, this was a ruse. What could be more out of proportion than a government labeling an avant-garde opera dangerous while it purged its own citizens?

Yet, the critic was right that Shostakovich’s score is shocking. Even today, the satirically grotesque dances, the brutal brass outbursts, and the wailing dissonances are jarring in their iconoclasm. To hear this score in the 1930s would be brain bending. No wonder the Russian public went crazy for it.

The opera’s plot, adapted from Nikolai Leskov’s short story of the same name, is itself brutal. Katerina Lvovna (Anja Kampe), of humble origins, is married to a wealthy merchant in the provincial Mtsensk district. Her husband, Zinovy (Evgeny Akimov), and her father-in-law, Boris Izmailov (Dmitry Belosselskiy), all but lock her away in their estate where she is wasting away from the tedium of a heavily restricted life.

One day, with her husband away on business, Katerina ventures down to the worker’s quarters. She comes upon a group of male workers who have thrown Katerina’s cook, Aksinya (Julia Dawson), into a barrel and are gleefully groping her for sport. The cook’s shrieks ricochet off pounding horn blasts. The gang of men laughs menacingly in rhythm, thrusting choreographically like a grotesque male burlesque rape fantasy.

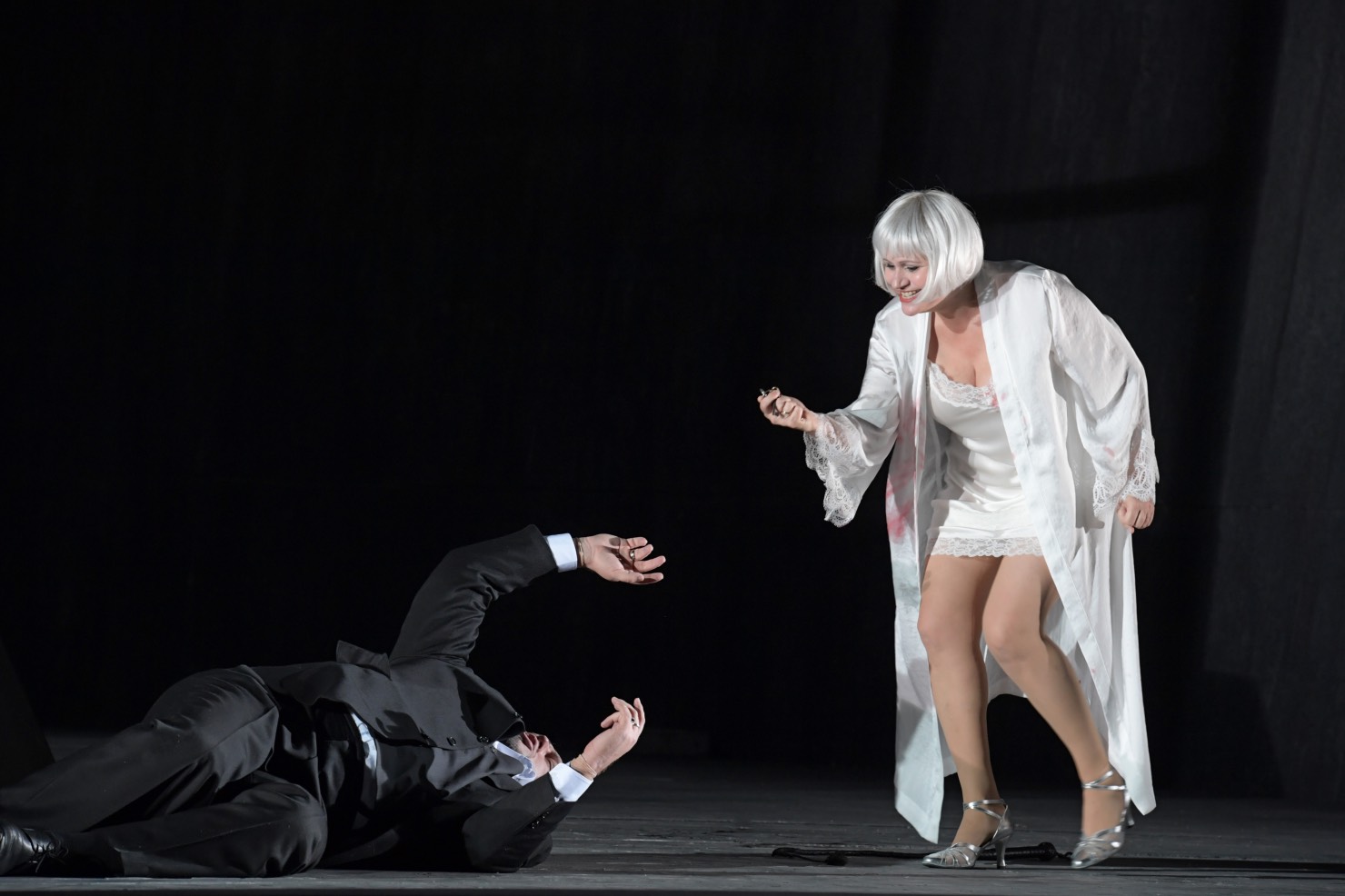

When Katerina intervenes, the leader of the crew, Sergei (Dmitry Golovnin), a recent hire who lost a string of jobs by sleeping with his bosses’ wives, talks her down with aggressive negging. When he grabs her, she asks him to relent. He’s gripping her hand so tightly that her ring is digging into her finger. Sergei persists. The scene breaks up, but shortly thereafter Sergei appears in Katerina’s room and continues his pursuit. Relentless, he drags her into bed – a gruesome start to an affair that leads to the murder of both Boris and Zinovy at the hands of the couple.

But what of Katerina’s loneliness? Her sole escape is a VR headset with which she views low-fi images of the outdoors. It hardly seems immersive, but she plays like she’s relaxed. A computer with an internet connection or a smart phone might be a more reasonable escape.

Banal cruelty dominates the domestic scenes. Sergey, Boris, and Zinovy all repeatedly abuse Katerina to different degrees but she seems more oblivious than hollowed out or disturbed. Kampe, who sings well, plays Katerina with a vague naturalism that evokes a dull inner life.

The score takes a lead role in the storytelling. Only Katerina’s (and later, the old laborer’s) music is largely sincere. Sergey’s duplicitous come-ons are expressed with Verdian schmaltz. When desperation sets in, his melodies go sour. Boris, the ghastly stepfather, gets the Scarpia treatment with a massive, crashing entrance theme. His melodies lack finesse and are to be brayed not sung.

The contrabassoon grounds the men’s actions in buffoonery. An extremely low, pumping ostinato that underlies much of their scenes can only be played crudely. Its repetitive peasant dance marks the men, regardless of their social status, as bumpkins. Yet, I couldn’t help relating the burps to the march before the tenor aria in Beethoven’s 9th symphony. Joy here may be dubious.

What’s disturbing, and Shostakovich reflects this in his music, is not just the characters’ cruelty towards Katerina (and Aksinya) but the pleasure they take in the cruelty itself. The gleeful dancing as the men assault Aksinya, the surrealist jig that a high priest (Alfred Reiter) dances at Boris’ funeral, the terrifying, ecstatic wedding march, and the chorus of biker gangsters, led by clarion-voiced baritone Iain MacNeil, who complain about not having enough crime to pursue like the sailors in South Pacific beg for a dame, all point to a patriarchy drunk with violence.

Both Kampe and Golovnin are extraordinary in terms of vocal technique and stamina. Neither voice diminished noticeably by the end of what is an enormously challenging sing. But neither voice translates the overwhelming circumstances of the opera into music that matches its stakes. Points for consistency, but where was the drama?

Belosselskiy’s singing was earthier. As Boris, he forcefully bellowed straight-toned arcs that, in their inelegance, matched the character’s brutality. Later, as the blind, old, forced laborer, who is a sort of a guardian angel to Katerina, he indulges in sumptuous legato singing, channeling the comforting voice of death.

The supporting cast, filled out largely by the Oper Frankfurt ensemble, sang admirably. Bass Anthony Schneider had a rich, even tone. Peter Marsh, who has keen comic instincts, was well-cast as the drunk who discovers Zinovy’s corpse, breaking Katerina and Sergey’s scheme wide open.

The orchestra, led by Oper Frankfurt Music Director Sebastian Weigle, found it’s stride late in the evening with the wedding march. A few intriguing moments in the score went by deemphasized or not quite coordinated. Some screws can be tightened and should be throughout the nine show run.

The Pravda review describes Lady Macbeth as “a game of clever ingenuity that may end very badly,” presumably for the young Shostakovich. But the composer managed to tactfully appease the oppressive Soviet regime while penning a remarkable oeuvre widely performed today. For Shostakovich, irony goes beyond the page.

Comments