The Flying Dutchman a stellar homecoming for HGO

ReviewAs I walked this past Friday into the newly repaired Wortham Theater Center, recently subjected to months-long repairs after having withstood the devastating inundation that last year’s tropical cyclone brought to bear upon the whole city of Houston, I could not help asking myself what impression Houston Grand Opera’s inaugural performance of Richard Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer would inevitably bestow upon its public, being, after all, the first time many Houstonians would return to this building that has supplied them with countless fulfilling cultural and community experiences. My impression was that it met, even exceeded, all conceivable expectations.

HGO’s triumphant return to this venue was replete with sheer authenticity of spirit, dedication, and craftsmanship from all quarters. Throughout this marathon performance, I was pleasantly touched by this production that treated the central narrative of redemption through love as something to be regarded passively, and not inhabited fully, to be believed, yet inviting scrutiny from all angles.

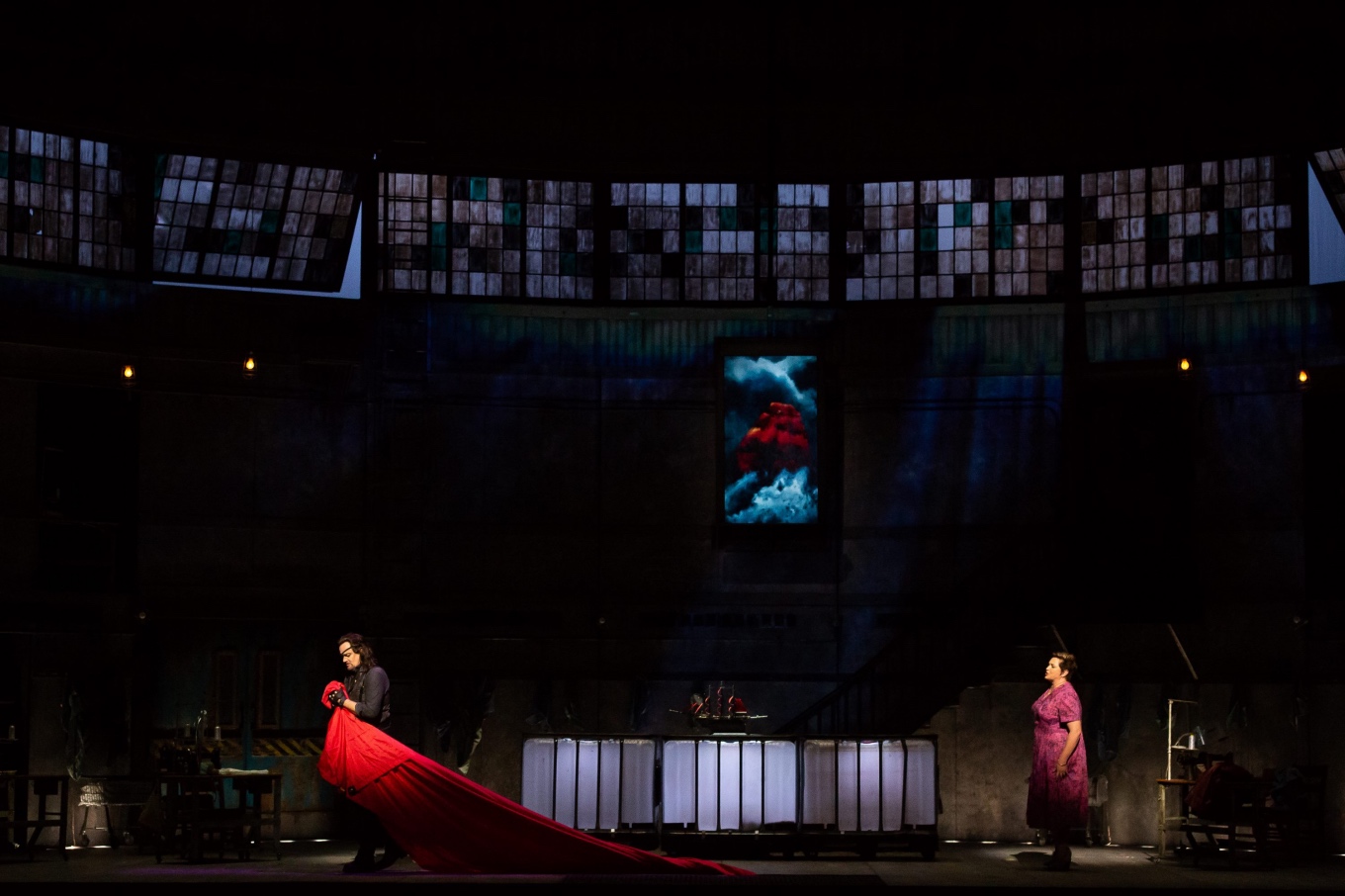

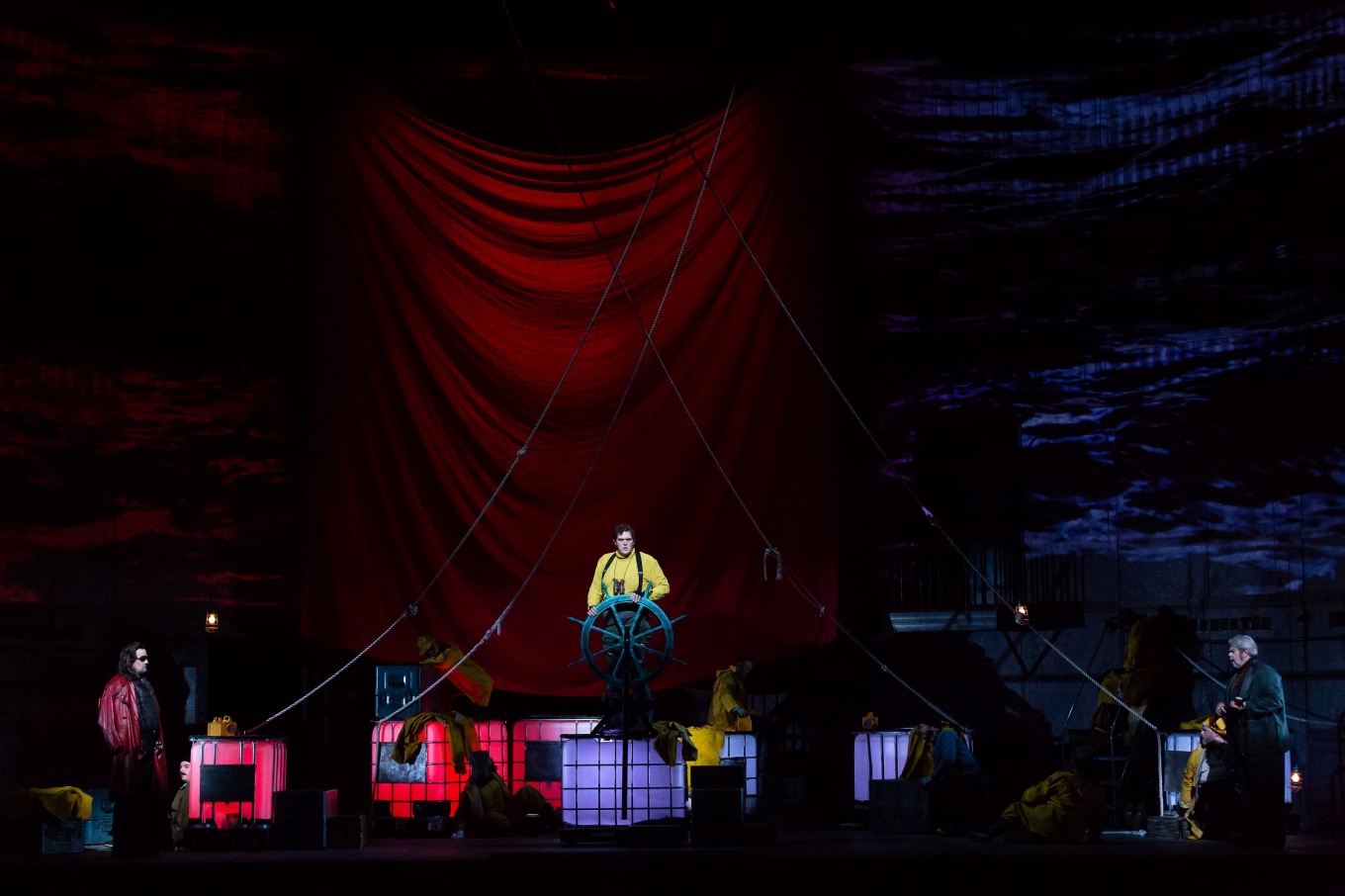

Throughout the overture, one perceived the use of various amorphous and colorful backdrops to complement the music, at times evoking an aurora borealis in both intensity and form, though the use of the color of dark blood red had a way of entering the picture at key structural moments. These sorts of vivid figures had a way of emphasizing the vivid nature of the score, especially since the onstage action had a way of being kept apart from the viewer, as if the audience were not actually therein immersed, but rather, kept at arm’s length. The elements of the production were therefore emphasized separately and not necessarily as the sum total of their parts, but this concept worked well to keep the two-and-a-half-hour-long work (performed without interruption) moving forward at all costs. Indeed, this opera actually felt quite short; perhaps my previous viewing of the company’s Götterdämmerung was ideal preparation for this singular experience.

As the Dutchman, baritone Andrzej Dobber brought to this character a gravitas that was not pretentious in the least, though it may have seemed quite impersonal to any audience members unfamiliar with Wagner’s tendency to indulge in grand philosophical monologues, though they are here not as extreme as in later works. Constantly fixated on the question of salvation to a degree that can in lesser hands become a mind-numbing caricature, Dobber was well-placed to make this existential quest compelling. Conveying through his uniformity of tone the world-weary traveler he is, he managed to simultaneously sound unbowed by tribulations, yet eager to spare his soul further exertions.

Senta (soprano Melody Moore) is another case in point. It is extremely difficult to make this role come across as compelling and sympathetic without exerting an unhealthy amount of effort in Wagner’s wide-ranging melody lines, and yet Moore managed to do so convincingly, yielding neither to an overly lyrical impulse nor to an overly histrionic bent. Having to fend off the well-meant intentions of a very agreeably prudish Mary (Leia Lensing, possessed of a natural and unforced low tessitura perfect for this role), and the less-than-visionary Erik (tenor Eric Cutler), she showcased the dichotomy inherent in feeling oneself called to a higher purpose that one finds so often in Wagner’s music dramas, yet not, being so above it all in the end, even in her quest for her ultimate purpose in life.

The aforementioned Cutler had a superb command of coloratura in his upper range, and indeed showed a great ability to navigate between registers, as Wagner is ruthless yet careful in demanding that he accomplish seamlessly. Combined with this, Cutler was skilled at portraying a character incapable of seeing beyond the present moment or beyond how a situation affects him personally. Daland (Kristinn Sigmundsson), the uncomplicated, amiably acquisitive old sea-dog whose acceptance of the Dutchman’s riches sets his daughter on a collision course with destiny, was very well-portrayed likewise, his tightrope between comic role and patriarch being a tough act to balance naturalistically without resorting to caricature. Though possessed of a certain breathiness of tone, Sigmundsson adapted this tendency well to his character, which makes me certainly intrigued to see him in other characters. His energetic steersman (Richard Trey Smagur) was likewise played for the occasional chuckle, as he had a very endearing, almost childlike way of standing about bewildered at the advent of any unusual events, particularly involving supernatural beings.

Speaking of said supernatural beings, the members of the Houston Grand Opera Chorus who portrayed them maintained the sort of spirit that this piece demands, and clearly relished their return to a space in which they were actually audible, after having dealt with particular challenges posed by the (nevertheless serviceable) George R. Brown Convention Center last year. From the lusty sailors’ choruses to the chattering spinning song to the Act III party number, this ensemble was consistently crisp, engaged, and unencumbered. The women were particularly good at depicting the sort of hopeless concentration on bourgeois frivolity which the Romantics so eagerly bemoan given any chance at all. A particularly nice touch consisted of the various lads who cluelessly put up their dukes in boxing pose as a challenge to the arisen crew of the Dutchman, whose wraith-like forms could be seen all around the ship when they were projected onto the vessel’s walls to give the impression of their being invisible.

Likewise, the Houston Grand Opera Orchestra was certainly exultant about once again playing in a space which displays their musical gifts to acoustic advantage. Artistic Director Patrick Summers is clearly in his element conducting Wagner; the orchestra was quite scintillating, and made this music drama sound fresh off the presses. The variety of orchestral color was well exhibited in relief, with an absolute minimum of effort; I was truly amazed at how the different sections maintained the requisite concentration over such a long span of time to keep their playing spontaneous and meaningful. It is true that Wagner is skilled at making this variety come across naturally without having to finagle excessively over details, but this performance was especially brilliant, making this work, especially in the more noisy passages, come across as the transcendent and unquestionably daring revolution it constitutes. Those who know my musical tastes will instantly understand why I was constantly asking myself, “Why do not more composers in this day and age take pieces like this as a textbook guide for how to tastefully write for the voice and orchestra with an unforced sense of heady modernity?”

I felt like I had somehow been transported to 1840s Dresden, and that this was the premiere performance of a work at the vanguard of even greater things to come. May we hope that this is the case with HGO’s coming seasons, and that, over the inevitable course of time, the diligence, expertise, and fulfillment the company have here displayed never languish or slacken.

Houston Grand Opera’s production of The Flying Dutchman runs through November 2. For details and ticket information, click here.

Comments