The price of vengeance: Rigoletto at ROH

ReviewVendetta: that infamous word, tarnished by association with Mafia bloodshed and The Godfather. Vendettas have a nasty tendency to self-perpetuate, as each act of retribution in turn generates further reprisals, ad infinitum. The burning lust for revenge can be passed on for generations, until groups have long forgotten why they despise their opponents in the first place. Vendetta plays a central role in Verdi’s opera Rigoletto. After all, one of the eponymous character’s most celebrated arias is “Si! Vendetta, tremenda vendetta!”

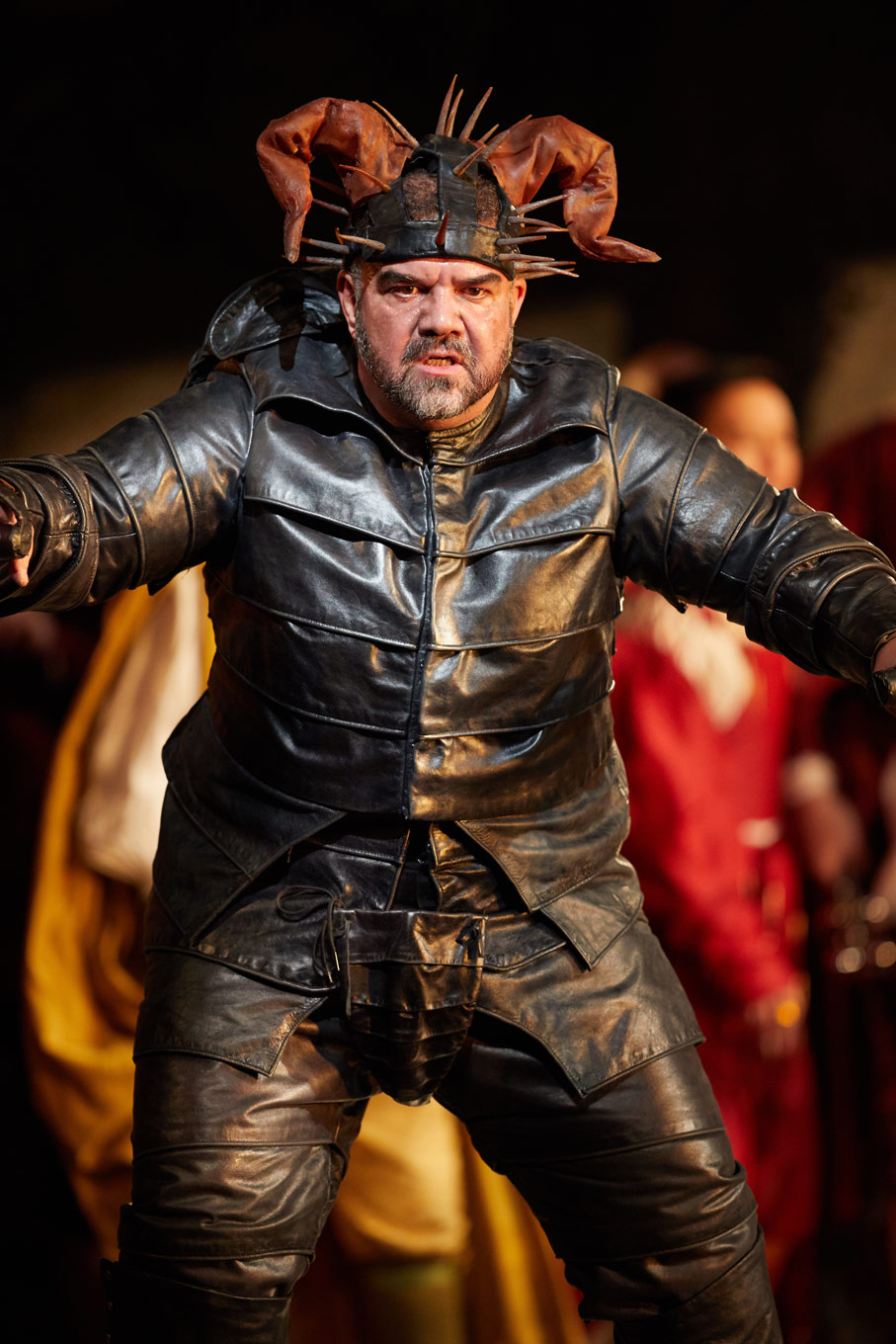

Rigoletto is a pitiful character. Hunch-backed, and in this production reliant on walking-sticks too, his job as professional pain-in-the-arse to the court of Mantua wins him few friends. The sole joy in his life is Gilda, his virtuous daughter. In contrast to her, the ball scene in the first act was sexed-up to the extreme. Given what I like to call the “Game of Thrones treatment”, exposed breasts and graphic sex occupied the stage, culminating in two chorus members being totally stripped naked. A bit much for the first fifteen minutes. Scene two meanwhile featured Gilda as the quintessential chaste maiden, swanning around stage in a silken white gown. Never in my life have I been so receptive to sexual purity.

Despite the misfortunes of his life, Rigoletto’s suffering only intensifies. He unwittingly assists in the abduction of his own daughter, leading to her rape. Though determined to seek revenge against the Duke, Gilda begs her father not to. At the end Gilda sacrifices herself to save the Duke, dying in Rigoletto’s arms.

Through their behaviour we see two radically different systems of morality clash. Rigoletto represents a machismo code of honour, seeking to avenge any insult and maintain his esteem, similar to the concepts of time (honour) and aidos (shame) in Classical Greek drama. In contrast Gilda represents traditional Christian morality, hence her costume of purest white. Despite being violated by him, she forgives the Duke, and when his life is imperilled she surrenders her own to protect his. Her actions parallel the Christian teaching that Jesus died for the humanity.

The opera contrasts these two opposing schools of ethics, one based on honour and the other on mercy. But Verdi doesn’t rush to any firm conclusions on which is preferential. Though Gilda is pitied as a victim of rape, her hunchbacked and ostracized father is equally moving. When Rigoletto plots revenge we eagerly support him. He is not an alpha male reinforcing his superiority but rather seeking justice for his only child. Rigoletto is the underdog, so of course we root for him.

It is only in the final scene that Verdi reveals his true colours, when Rigoletto discovers that the body before him isn’t the Duke but his only daughter. Our hearts ache as he weeps over the loss of his only joy. But Verdi is clear in his message: no one can come out of vendetta unscathed. Those who seek vengeance will be paid back in full. Even those who appear justified in their actions, such as the outcast Rigoletto, cannot escape the consequences. If he had not sought revenge then his daughter would not have died. It is only through forgiveness that we can heal and move on. Vendetta is nothing but a whirlpool, growing and growing until it devours everything.

The scenery was heavily sombre, a suitable reflection of the opera’s moral themes: here we have a world of ugliness, dominated by violence and spite, abuse and tragedy. Gilda, garbed in piercing white, appears as the saviour to this wretched world. And while the courtiers and Duke might be magnificently arrayed in dazzling jewel tones, the sumptuousness merely disguises their inner barrenness. A patch of barbed wire symbolised Gilda’s fragility in this ruthless world. Giovanna, Gilda’s nurse, meets the Duke and the two converse through the fence. A slit in the middle of it, hinting at Gilda’s sexuality, becomes the medium for the Duke to bribe Giovanna, and he punches his fist through it in boorish coarseness. Gilda is clearly too pure for this world.

Covent Garden’s Rigoletto emphasises the ethical complexities which pervade this opera. This is not a simple tale of good triumphing over bad. Rigoletto could easily be portrayed as a villain, inadvertently assisting in the abduction and killing of his own daughter and plotting the murder of the Duke. But instead he is a victim, further misled by his own warped morals. Clutching Gilda’s corpse he cries “la maledizione!” (the curse). But was it really the curse which brought about his misfortune or his own actions? Just as in reality, the answer is far from straightforward.

Rigoletto continues at the Royal Opera House through January 16, 2018. For details and ticket information, follow our box office links below.

Comments