The singularity of Fauré in Oper Frankfurt's Pénélope

ReviewNo composer’s music has sounded quite like Gabriel Fauré’s. Immersed in sacred Renaissance and Baroque polyphony at a young age, the composer learned that modal harmony allowed for choices out of reach in the prevailing Germanic post-classical paradigm. Pianist and author Graham Johnson describes how in the modal system “one has simply to choose how to interpret any given chord and engineer a resolution that conforms with that interpretation” rather than be bound to Wagnerian chromaticism for complexity and variety.

In Fauré’s music, one deliberately chosen pitch can shift the harmonic landscape in a subtle but entirely novel way. The clearest example is the raised fourth scale degree in the Lydia theme, which the composer developed and transformed over his entire life and which is the thesis of his second opera, Pénélope. One pitch distinguishes the theme’s lydian mode from a conventional major scale, yet from that single lifting alteration and the myriad harmonizations it engendered, Fauré fashioned a rich dialect to elucidate the sublime hope of love.

In Pénélope, whose story comes from the end of Homer’s Odyssey and tells of Ulysses’s return and reunion with his wife Pénélope, the theme is stitched into the fabric of the score. As the couple grows nearer, it ventures into the foreground, gaining prominence over the two hour work. Finally, the couple is reunited and the theme swells with the full force of orchestral strings, erupting and oozing as Fauré’s meticulous structures, like Ulysses’s careful scheme to regain his kingdom, bursts into the open and blooms with sensuality.

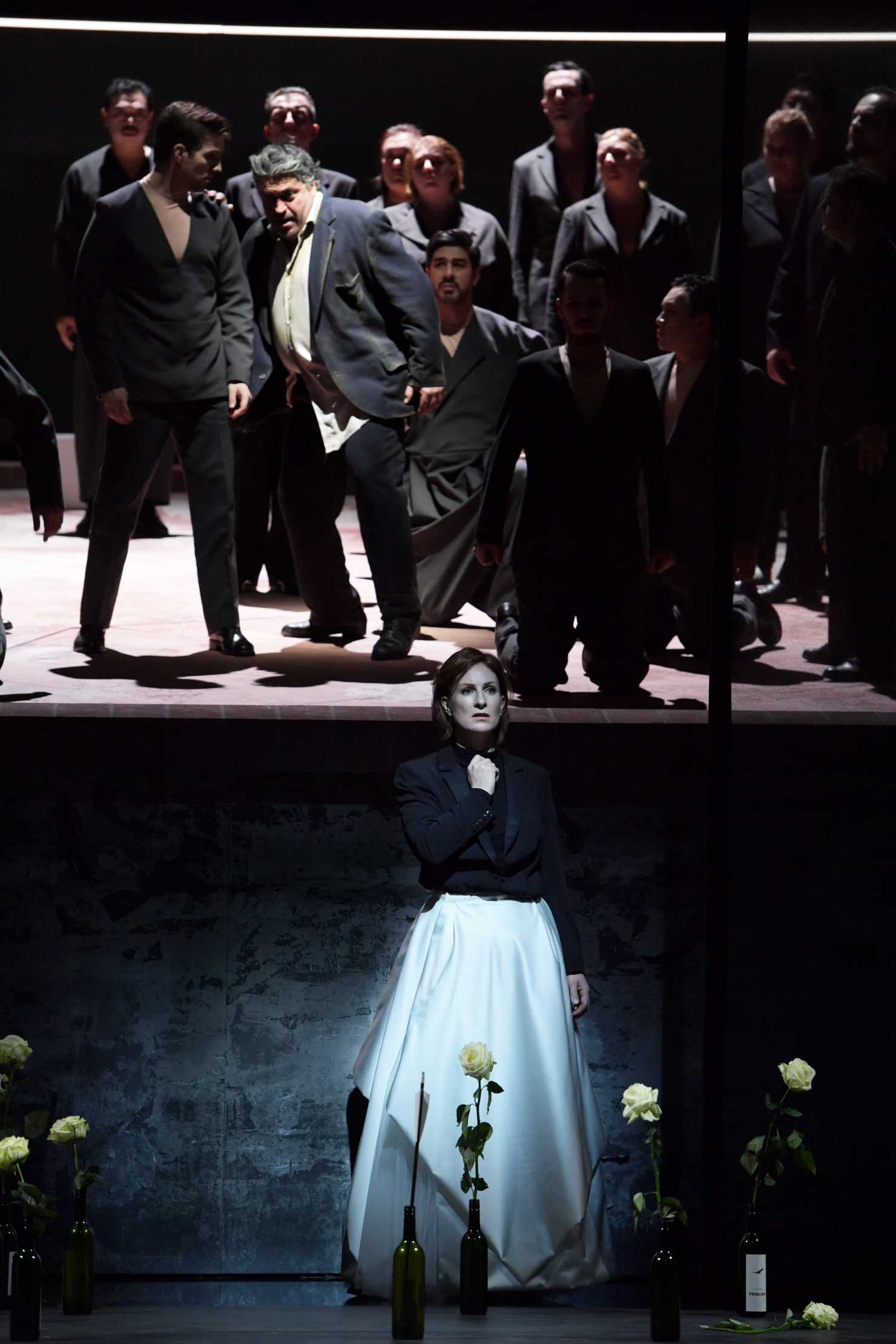

Oper Frankfurt has mounted a new production, by director Corinna Tetzel, of Fauré’s too seldom performed opera. Set on the rooftop of an unremarkable apartment building, meant to signify the decay of Pénélope’s queendom in Ulysses’s absence, recognizable objects (a rusted out satellite dish, deck chairs, black suits and yellow dresses) clash with baffling unrealities. A scrim, lit by a neon ceiling frame, drops to the front of the stage like a flattened mesh entrance to a large backyard trampoline. Characters inhabit the no man’s land surrounding the apartment’s roof and communicate to those on the rooftop as though they were in the same room.

Pénélope awaits Ulysses return. It’s been 20 years and the queen’s suitors have grown impatient. Once the queen finishes weaving a funereal shroud for her father-in-law Laertes, she will be forced to choose a spouse. But each night, she unravels her day’s weaving.

The men indiscriminately abuse Pénélope and the women of her kingdom, theatrically throwing them around like amateur wrestlers. Yet their violence succeeds as seduction and they are rewarded with sexual favors. The men are thinly drawn, each portraying a single affect – incredulity, apathy, viciousness and predation. The women are sexualized totems who have little effect on the larger story.

The opera should be an ideal vehicle for Paula Murrihy, and in a more thoughtful production, it would be.

Projections also have little effect on the story. During the first act, at the back of the set, full color security cam-like footage of the roof shows Pénélope wandering aimlessly as she waits for Ulysses. If you wonder whether waiting is tedious, see for yourself. Later, the screen is unveiled to reveal, dum dum dum, television static. Let’s call it technical difficulties and leave it at that.

That night, the suitors catch Pénélope unraveling her woven shroud. Furious, they declare that she must choose a husband the next day. Ulysses, who, disguised as a beggar, has been in the castle the whole time, advises his wife to choose a suitor based on which of them can string his notoriously unyielding bow.

The scene challenges directors. Do you play the competition literally or abstractly? Or, do you avoid it entirely?

The roof splits in half like a city street in a B-movie earthquake, separating the suitors from Pénélope. Magic (presumably) restricts the men’s movements. Ulysses, from no man’s land, circles the roof and emerges atop it, joining Pénélope, who melts in his embrace. It is declared: Ulysses has strung the bow.

In Homer’s Odyssey and likewise in the opera’s libretto, after Ulysses strings his bow, he slaughters the suitors mercilessly. To see Ulysses, who has been described as an unassailable hero, commit acts of gratuitous violence questions what it means for society to prize brute strength and warrior ruthlessness over mercy and forbearance. Right at his most heroic, Ulysses’s pedestal cracks. However, in this production, the men are ushered off stage without much ado. Ulysses remains a symbolic ideal and bland storytelling triumphs.

The overture seemed to last but an instant, like an early morning dream, a hallucinatory scrape against bliss before you wake to a less favorable reality.

The opera should be an ideal vehicle for Paula Murrihy, and in a more thoughtful production, it would be. She sings Fauré exceptionally. Her timbre is supple and her zwischen mezzo range suits the role’s peculiar register surprisingly well. Considering the role was written for a Wagnerian (and the standard modern recording stars Jessye Norman) it’s remarkable how seldom the orchestra overshadowed Murrihy’s tone.

The role of Ulysses, played by the well-cast Canadian tenor Eric Laporte, likewise has an unusual range that, most of all, requires a durable yet noble middle voice, with power towards its top. Like Murrihy, Laporte gives the kind of egoless performance the music requires. Ulysses isn’t a role that rewards tenorial vanity and Laporte is up to the challenge of thrilling the audience through linguistic subtlety and elegant phrasing rather than with climactic high notes, which in Fauré’s music are often beside the point.

Aside from a single moment of lovingly playful invention from Božidar Smiljanić (Eumée), who teases a shepherd child, pantomiming that her arrow has stuck his chest, the most effective staging in the opera was no staging at all. Smiljanić, with his rippling bass-baritone, along with the Laporte and Murrihy, seemed to realize that it was more powerful to face out and sing than indulge in histrionics. When the singers voices and the music itself was put front and center, the evening came into focus.

Another bright spot was the orchestra and its leader for the evening, Joana Mallwitz. The overture was especially promising. Like the crisp layers of a mille-feuille gently separating into morsels of sumptuous yet refined complexity, Mallwitz and the orchestra served up delicately overlapping musical motifs, transforming themes and transporting the audience. The overture seemed to last but an instant, like an early morning dream, a hallucinatory scrape against bliss before you wake to a less favorable reality.

Fauré, with characteristic modesty, never presumed he would be remembered by posterity. But this production shows that his music, when performed with grace and expertise, endures unassailably no matter the circumstances.

Comments