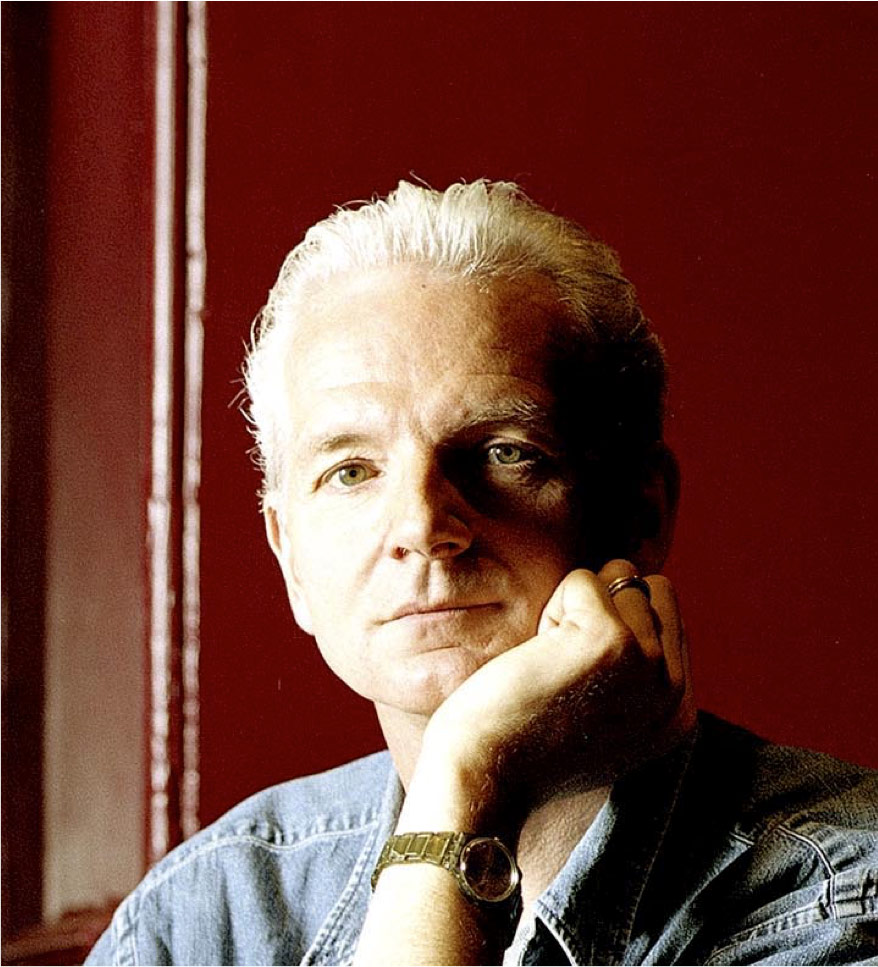

Tim Albery: flawed operas & falling empires

Interview“I remember when I thought I might want to be a director,” says Tim Albery, looking back on his childhood and teenage years spent as the child of theatrically-inclined parents. “My father was walking along the street after rehearsal with an actor called Daniel Massey - he was playing the lead in some not-terribly-good musical,” he recalls. “They were talking about a particular scene and why it didn’t work, and I piped up with, ‘well, that bit there, I never understand what’s going on in that bit there,’ or some such contribution.” Albery laughs at the memory of his 15 year-old self, whom he calls “too young to have an opinion,” and remembers his father and Massey laughing, too. “I guess that was probably a sign that I was quite interested in the shape of a scene.”

Albery is certainly part of a theatrical pedigree, the son of producer Donald Albery and the grandson of director Bronson Albery, both of them West End theatre producers, while his mother, Heather Boys, was an actress. Tim Albery has many memories of holidays spent with his family, on tour with shows or sat in the Royal Festival Hall - where his father ran the Festival Ballet for some years - watching the annual rehearsals of The Nutracker. “I always associate Christmas in my early teenage years with The Nutcracker,” he smiles.

Albery’s own directing career began in theatre, and his first chance to work in opera came at around 30 years old, with an invitation to direct The Turn of the Screw. His exposure to opera was limited to one not-so-great production he had seen, but his theatrical experience did include work with music, choreography, and collaboration with composers. “So I agreed to listen to the piece,” he says, adding that Britten’s opera is “something of a gift for a theatre director, because it doesn’t pose a lot of the formal problems that opera has many times.”

The Turn of the Screw seemed not only a gift, but a beginning to Albery’s successful career as an opera director. His notable work with Britten operas - which he calls “astonishing” in their construction - continued with Billy Budd, starring Thomas Allen in the title role, and Peter Grimes with Philip Langridge, both at English National Opera, and later A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Metropolitan Opera. More recently he staged Grimes on the Beach, as part of the Britten centenary, outdoors on the beach at Aldeburgh, where Britten lived and where Grimes is set.

“It’s more complicated than it looks at first sight.”

Albery is currently in Toronto, staging his production of Richard Strauss’ Arabella at the Canadian Opera Company, a co-production with The Santa Fe Opera and Minnesota Opera. Arabella marks the latest in the director’s history with the COC, which also includes Götterdämmerung (2006 and 2017), Aida (2010), and War and Peace (2008). The through-composed, theatrical pacing of Britten’s operas is also found in those by Strauss, yet Arabella comes with some unique hurdles for a director.

“One of the challenges in this piece,” says Albery, “lies in the many one- or two-bar pauses between people speaking.” Strauss is known for intention, not just indulgence. “But there are moments when it can be tricky to uncover the reason for the pacing during the more conversational scenes”, Albery admits.

Arabella is the sixth and final collaboration between Strauss and librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, preceded by Elektra, Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, and Die ägyptische Helena. Hofmannsthal died before having the usual period of editing and revision, resulting in what Albery calls a “flawed” piece. “The last half of the evening has problems, which led to what have now become pretty standard cuts,” he explains. “But the opera speaks to a lot of good things, I think, about how we live our lives.”

“I do somehow equate it with Così [fan tutte], because it’s about love, and what two young women expect out of life,” he says about the story of a financially desperate couple and the resulting fates of their two daughters, Arabella and Zdenka. “She’s totally aware of what’s demanded of her, and hates it,” says Albery of Arabella, who must choose one of the shallow but wealthy Viennese aristocrats who are pursuing her, in order to stave off her family’s imminent bankruptcy. “But on another level, she can quite easily deal with it if she has to; a life of ease, wealth and amusement has great attractions.”

An arranged marriage certainly doesn’t appeal to most women today, but within the context of Arabella’s 19th-century Viennese world, her options are manageable. “I love the fact that she loves to party, and that people like her suitor Elemer amuse her and are easy to control,” says Albery. “It’s more complicated than it looks at first sight, in terms of who’s abusing whom. But Arabella also knows instinctively there can be another better, purer kind of life and of love, and when it arrives out of the blue she grabs it with both hands.”

“Rhythm, silence, speed, all of those things must be discovered in the language.”

Having worked on both ends of the theatrical spectrum - from straight play to through-composed opera - Albery has found that music and rhythm appear in all genres. With theatre, “in a way, as a director in conjunction with the performers, you are writing the music,” he explains. “Rhythm, silence, speed, all of those things must be discovered in the language and there is enormous freedom of choice.” In opera, “there is a different and sometimes surprising room for interpretation within the formal constraints of the music to be investigated by director, conductor and the singers.” Albery has seen theatre directors frustrated by the parameters of opera: “they don’t take pleasure in it.”

“The floors of various opera houses are littered with theatre directors who didn’t make a happy transition to directing opera,” he says. “They just found the restriction and ‘compromise’ of the music too frustrating to deal with.”

Next to the sense of narrowed choices some directors feel within the opera world, the process of working with singers is perhaps ironically freeing. “I often surprise people who don’t know about opera when I say in a wild generalisation that singers on the whole, compared with actors, are much more open-minded about how a production might be,” says Albery. He suspects one reason may be simple: singers are much more likely than actors to perform a role in several productions. For an actor “who will only play King Lear once,” it’s harder to approach a production with flexibility when there’s no “next time” in mind.

“It won’t be the first time empires have fallen, will it?”

I couldn’t help but ask Albery, with his time spent working in opera houses worldwide, if he had any wisdom on the topic of maintaining audiences - and perhaps more importantly, building new ones. Of course, any solution to be found is not one-size-fits-all.

“It depends on where you are, and what the culture of the place you’re working in is,” says Albery. He points to obvious hurdles, like companies with large overhead costs (“The companies with buildings are those with commitments to paying a lot of year-round salaries.”) and a tradition - even a perceived dependency - on patrons buying season-long subscriptions, a trend he says is “dying”.

“How many people nowadays are prepared to say, ‘on January the 15th of next year I’m going to be sitting in row F, seats 3 and 4’? Life isn’t like that for most people,” he says. “They want to know if it’s any good, or feel that it’s an event, they want to know all those things before buying a ticket.”

Albery points to companies trying different solutions, such as using multiple, different-sized venues so they can present a far more varied repertoire, or having a festival-based performance schedule with many events over a short time period.

And he sees one very positive development. “More and more companies are finding that the new pieces they do are turning into the box office events,” Albery says. “If the model of these institutions can change to adapt to that, then I think that’s great.”

“Things are changing, and some huge organizations will possibly go by the wayside. It’s sad to imagine, but it won’t be the first time empires have fallen, will it? And I don’t think it’s necessarily in the long term disastrous. However different it may look and sound in fifty years, opera does have a future.”

Tim Albery’s production of Arabella runs at the Four Seasons Centre October 5-28. For details and ticket information, follow our box office links below.

Comments