"Veggies in the morning, and melodies throughout the day"

InterviewWhen composer Edward Thomas needed a librettist for his opera based on the Eugene O’Neill play Desire Under the Elms, he did the sensible thing: he looked in the newspaper and in the phone book. (This was 1987 when people still used such things.) In the newspaper he observed that Joe Masteroff was enjoying a revival of his great musical Cabaret (for which he wrote the book) so Mr. Thomas simply looked up Mr. Masteroff’s number and called him. Thus was born a collaboration that produced a musical and two operas.

One of those operas, Anna Christie, just enjoyed its world premiere in New York, produced by the Encompass New Opera Theatre. (Reviewed here 10⁄13.) The opening weekend coincided with Mr. Thomas’ 94th birthday. Mr. Thomas attributes the maintenance of his “faculties” to eating vegetables five or six times a day (for breakfast) and working out every day for the last twenty years. (He lifts weights and is up to forty push-ups.)

The journey to opera for Mr. Thomas is the most unlikely of stories. Growing up he had no musical training whatsoever. He tried to learn the violin but was told by his teacher “You’re never going to amount to anything in music!” His parents next gave him a guitar and he was able to play a few things by ear, such as the Yugoslavian folks songs sung by his mother, but couldn’t read a note. Music, as it would turn, not only consumed almost the entirety of his life, but actually saved it.

Assigned to the 3rd Infantry and the invasion of Italy during WWII, Mr. Thomas watched his fellow soldiers cut down by the score just as they disembarked on the beaches of Sicily. Recounting some of his war stories, Mr. Thomas has to pause for a moment during this interview. “I get chills – it suddenly struck me,” he says quietly. There would be many battles to come as the Army would liberate Italy and Mr. Thomas feared he wouldn’t survive. But one day an officer announced that he was looking for musicians for the Army Orchestra. A lot of hands shot up in the air to volunteer – this was a chance to get off the front line. But Mr. Thomas could not read music and had to be persuaded to go to an audition by a couple of his compatriots. The officer in charge, as it turned out, needed a guitar player who could play popular songs at parties and at the officers’ mess. Mr. Thomas could do that. As for the band itself, the officer told him he could play the cymbals. “How do I do that?,” he asked. The officer said, “Start when we start and stop when we stop.” As a result, Mr. Thomas did not lose his life on some unknown road in Europe but was allowed to continue on the road to opera (and, eventually, a 94th birthday.)

Mr. Thomas had never even heard an opera until he was in his early twenties. His future in-laws were Italian and played Puccini records. Mr. Thomas would listen when he’d visit, then recall the big orchestral sound and verismo melodies on the way home. Then one day in the car, he heard a completely original melody that suddenly came into his head and he began to cry. From there on – and to this day - melodies have come to Mr. Thomas “incessantly.” A composer was born.

After the Army, he knew music would be his life. He studied and learned how to play the guitar for real, practicing five or six hours a day so that he could “sight-read anything.” As a result, when he got married he was able to support his wife and small children playing on gigs and in studio sessions. He found that he had a facility for writing “jingles” and so began a thirty-year career on Madison Avenue. It was a good living – composers make residual payments every time their work is played. Mr. Thomas recalls that when he would hear his music on a radio commercial he would say to his wife “There’s twenty-four bucks, honey!”

But serious music was always his passion and to that end he applied to study with Tibor Serly, a harmony expert and a protégé of Bela Bartok. During his interview, Mr. Thomas remembers saying “I know all about harmony” and Mr. Serly exploded into a Toscanini-like outrage, slamming his hand on the table. He then took a score by Mr. Bartok off the shelf and demonstrated its complexity to point out Mr. Thomas’s youthful arrogance. “It was the epitome of humility,” as Mr. Thomas recalls with a chuckle. But Mr. Serly saw something – or rather heard something – in the young man. After Mr. Serly heard a short recording Mr. Thomas had made of an orchestration, Mr. Serly agreed to become his teacher.

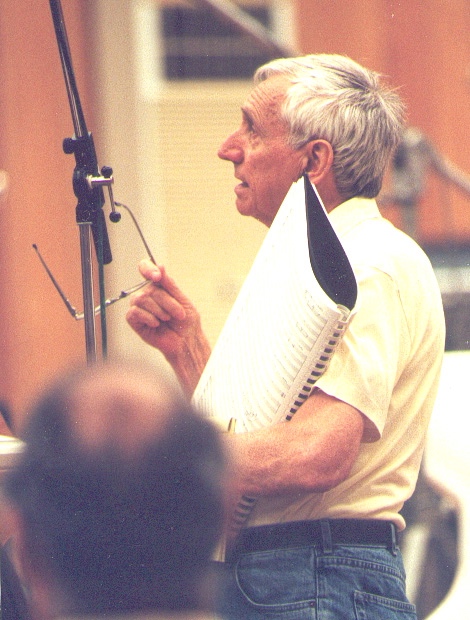

In 1961, after Mr. Thomas had studied with Mr. Serly for about six years, he finally wrote his first orchestral piece. Mr. Thomas proudly displays to this reporter the score for 60-plus instruments. (see photo) Mr. Serly remarked, “You’re a good orchestrator” and that was about the highest praise one could get from the maestro.

Mr. Thomas continued to write some “serious” music over the next two decades – Reflections for Violin and Piano, Fantasy for Oboe & Strings, a String Quartet and a Clarinet Concerto - but his greatest creative output has been since his retirement from the advertising industry. Perhaps not a coincidence.

He has been especially prolific in the last thirty years or so. About fifteen years ago, at the tender age of eighty, he was commissioned by Stanley Drucker, the first clarinet chair with the New York Philharmonic, to write a Fantasy for Two Clarinets and Orchestra that Mr. Drucker could play with his wife, who is also a professional clarinetist. It is also during this period of time that Mr. Thomas has composed all of his works for the stage.

With a penchant for a good tune and as a longtime theatre lover, it was inevitable that Mr. Thomas would turn his attention to musicals. He read the story of the infamous WWI spy Mata Hari and thought it was perfect for the world of musical theatre. (Equally as infamous as Mata Hari herself, was the show’s producer, David Merrick.) Mr. Merrick, lyricist Martin Charnin (Annie) and book writer Jerome Coopersmith began out-of-town tryouts of Mata Hari in Washington, D.C., and it would prove to be one of the most infamous flops in Broadway history. (In fact it never made it to Broadway.) During a particularly disastrous preview, reminiscent of Noises Off or The Play That Goes Wrong, leading man Pernell Roberts was hit in the head with a flying scenery hook and the actress playing Mata Hari was caught half-naked during a costume change She was also caught scratching an itch after she was supposedly shot dead by the firing squad. Afterward, Mr. Merrick gathered the creative team. He announced that the show would continue on to Broadway but as a spoof. After all, the audience was laughing for most of the show and, in Mr. Merrick’s opinion, the audience is always right. Mr. Thomas and director Vincente Minnelli were game to make the changes, but Mr. Charnin and Mr. Coopersmith were not.

Mr. Thomas also wrote Six Wives, a musical based on Henry VIII (with a book by Joe Masteroff.) Writing a successful musical is perhaps one of the hardest of all theatrical endeavors. Even Rodgers & Hammerstein and Kander & Ebb had well-known struggles. But having shown the chutzpah to climb that craggy, creative mountain, Mr. Thomas then decided to scale Mt. Everest and write not one opera, but two. Mr. Thomas’s head filled with melodies as he read Eugene O’Neill play, Desire Under the Elms, and an opera seemed like a natural progression of the work. The same thing happened when he read Anna Christie.

Both adaptations have been described by reviewers as “folk operas”, reminiscent of Copeland and Barber but Mr. Thomas eschews any labels. The works are lush, romantic and pastoral – even the recitative, which is normally sing-speak, is beautiful and harmonic. He has been criticized for a lack of “dissonance” in his composition. Mr. Thomas answers such critics with a smile and a simple “that’s their problem.”

At 94, Mr. Thomas has completed his latest opera – so what’s next? That’s not a question asked of too many nonagenarians. But Mr. Thomas is almost ready to get to work again. Having devoted the last two years to orchestrating Anna Christie, he’s taking a little break. He says he’s just waiting for the passion of artistic inspiration to hit him and give him a reason to use all those melodies that he continues to hear inside his head. He ponders that there might be a few short pieces over the next few years and perhaps even another opera. And having celebrated his birthday earlier this month with the opening of Anna Christie, he ponders what it might be like opening a new work when he’s one hundred.

Some of Mr. Thomas’s compositions, such as Fantasy for Oboe & Strings can be heard on YouTube.

Comments