Wozzeck: The Full Kentridge and Beyond

ReviewFin de siécle Vienna sets the time and place. The Second Viennese School and most importantly Alban Berg’s humane refinement of Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system, or atonality, distinguish the composer. The opera is Berg’s Wozzeck, a relentlessly grueling story of degradation and exploitation.

In skillful musical hands and voiced by intelligent singers, it produces passages of startling intensity and surprising beauty. Over time two very different performances and a live recording, all possessing that remarkable combination of beauty and intensity, have served to shape my view of this indispensable piece.

Wozzeck holds a special place in the operatic mind of this writer. A savvy professor at the University of Michigan told us that her class would show how opera moved from here to there. Here was when she played a few moments from a recording of Monteverdi’s spacious and elegant Orfeo in which our hero laments his lost Euridice. There arrived with the anguished voice of Wozzeck, a lowly solider, railing against the tumult of a huge orchestra as he confronts Marie, his unfaithful common-law wife. In those moments between the here and there the class glimpsed not only the origin of opera, but a work that embodied the birth of modernism.

Most recently Wozzeck appeared at the Metropolitan Opera in what might be termed the full Kentridge. A new production, the dominion of South African artist, William Kentridge, is a joint venture of the Met, the Salzburg Festival, the Canadian Opera Company and Opera Australia. It’s worth mentioning the partners in this production if for no other reason than to anticipate its longevity and reach as well as to commend the cooperative economics.

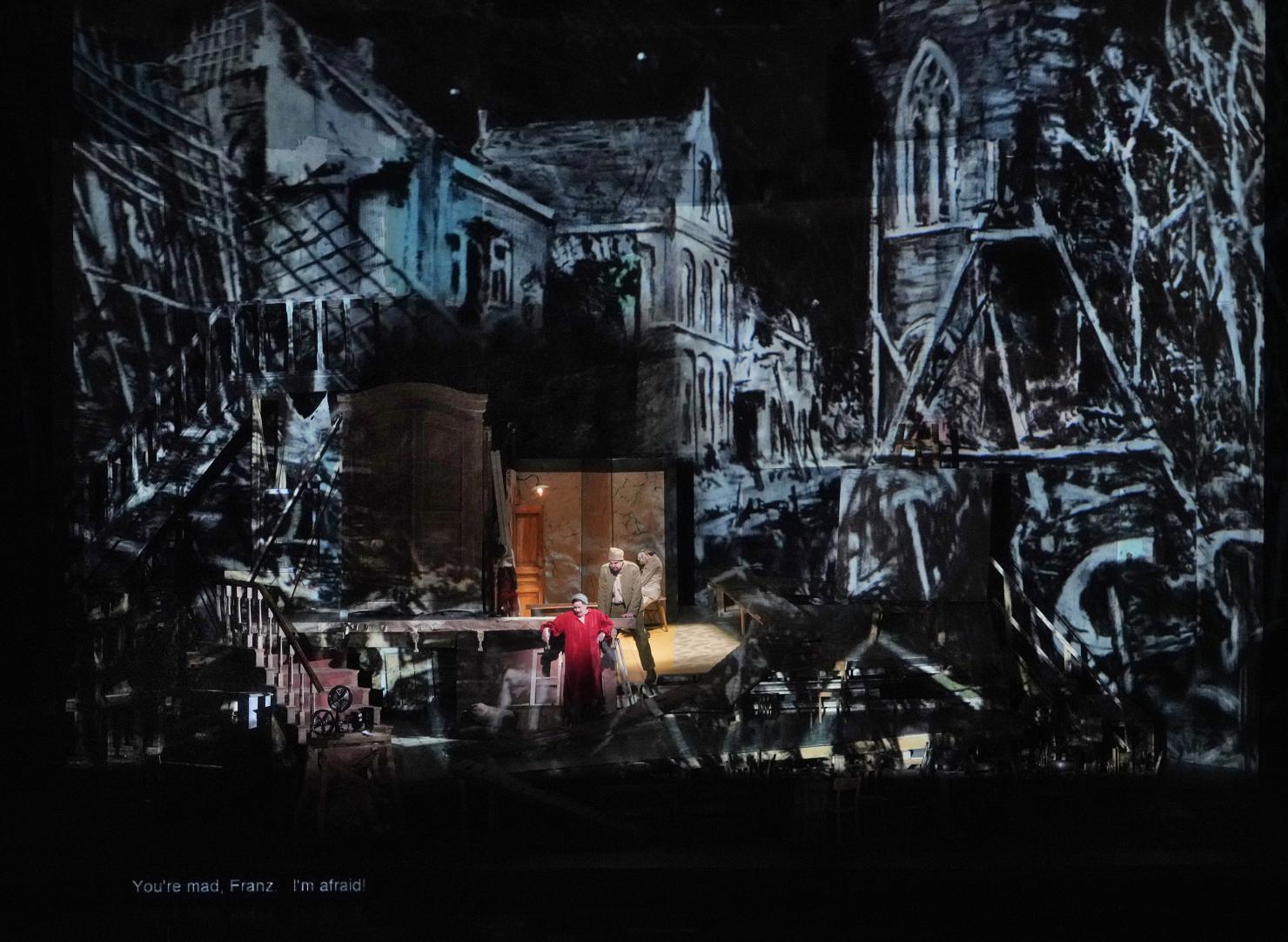

This is Kentridge’s second Berg outing for the Met, the first being his Lulu that gained clarity and a sense of sensual abandon through visual abstraction, torn paper and black ink. (Lulu is back at the Met next season by the way.) Kentridge’s vision of Wozzeck employs a set designed by Sabine Theunissen, best described as epic levels of ruins and rubble, and projections by Catherine Meyburgh that illuminate the title character’s frame of mind and exterior world. More an art installation than a production concept, it works as kinetic sculpture and sometimes like a gigantic ant farm.

Berg did not place the opera in a particular time or place. Smartly Kentridge has situated it prior to World War I rather than the usual setting that coincides with Georg Buchner’s 1825 play, the opera’s source material. Kentridge’s evocative charcoal drawings emerge as visual clues. Powerful and oddly playful, they are political, geographical and personal in nature.

Disaster is clearly anticipated. Effective placement of the principal singers, deft use of film and the fluid movement of a large cast keep the eyes of the audience tightly focused yet on the move. Illuminated by Urs Schönebaum’s ingenious lighting, the production is as alive and turbulent as the music.

Peter Mattei takes on Wozzeck with a ferocity that physically alters his bearing. Audiences accustomed to this great baritone’s elegant and expressive singing in roles like the swaggering Almaviva and the anguished Amfortas will find his writhing and mental agony something of a shock. Soprano Elza van den Heever as Marie, with her plush sound and gleaming high notes, brings moments of frustrated hope to this sloven character. She possesses a radiance that is undiminished by her dire circumstances and demeanor. Met music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin and his formidable orchestra mine the romanticism of Berg’s score to clamorous and shimmering effect. This team finds the strange beauty the lurks within this masterful work.

There was a different kind of beauty to be experienced in 2012 when London’s Philharmonia Orchestra under Esa Pekka Salonen came to New York’s former Avery Fisher Hall with a Wozzeck in concert. The title role was sung by the esteemed Simon Keenlyside. Instead of an elaborate production design or for that matter any set at all, the singers were relegated to the lip of the stage which was otherwise occupied by the orchestra. Known for the intense physicality that he brings to his roles, one could envision Keenlyside hurling Wozzeck’s madness into the audience. Fortunately he didn’t. If there is one thing Wozzeck isn’t, it’s participatory theater.

Marie, sung by Angela Denoke, who knows her way around Berg having sung Lulu’s cohort/victim, Gräfin Geschwitz in Vienna and Hamburg, stayed on her mark as Keenlyside literally lurched around her. So convincing were their abrupt movement and grotesque gesturing that any additional theatrical embellishment seemed unnecessary, even unwelcome. Keenlyside emerged a broken but pitch-perfect wild man. Denoke maintained a lustrous sound but was hard as nails. The orchestra was blazingly bright with sharp edges and dissonance overriding romanticism. Salonen and the Philharmonia seemed to thrive on the atonality. The results were brilliant. How different the effect of the full Kentridge was from this straightforward and explosive concert.

Some may argue that less is more, that this stark opera should stand on its own free of encompassing theatrical effect.

There is no doubt that Berg’s composition comes through vividly whether in staged or concert form. Some may argue that less is more, that this stark opera should stand on its own free of encompassing theatrical effect, but it would be reductive thinking to disregard the visually absorbing and thought-provoking experience that a full Kentridge provides. Others might think that such a challenging opera requires theatrical effect to make it more accessible. Quite simply it doesn’t. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for experimentation.

For the listener, alone with whatever device that is producing the sound, Wozzeck sits well on the ear, especially when some familiarity is developed with its 15 scenes arranged over three acts. In fact unfettered of anything but the voices and music, the listener becomes more aware of a distinct orchestral approach and vocal interpretations. True, it’s not the same as being there. But it does approach being in there. If anything can counter the depressive themes of Wozzeck, it’s an imagination spurred by the richness of the work.

Wozzeck doesn’t gather dust nor does it induce a speck of nostalgia

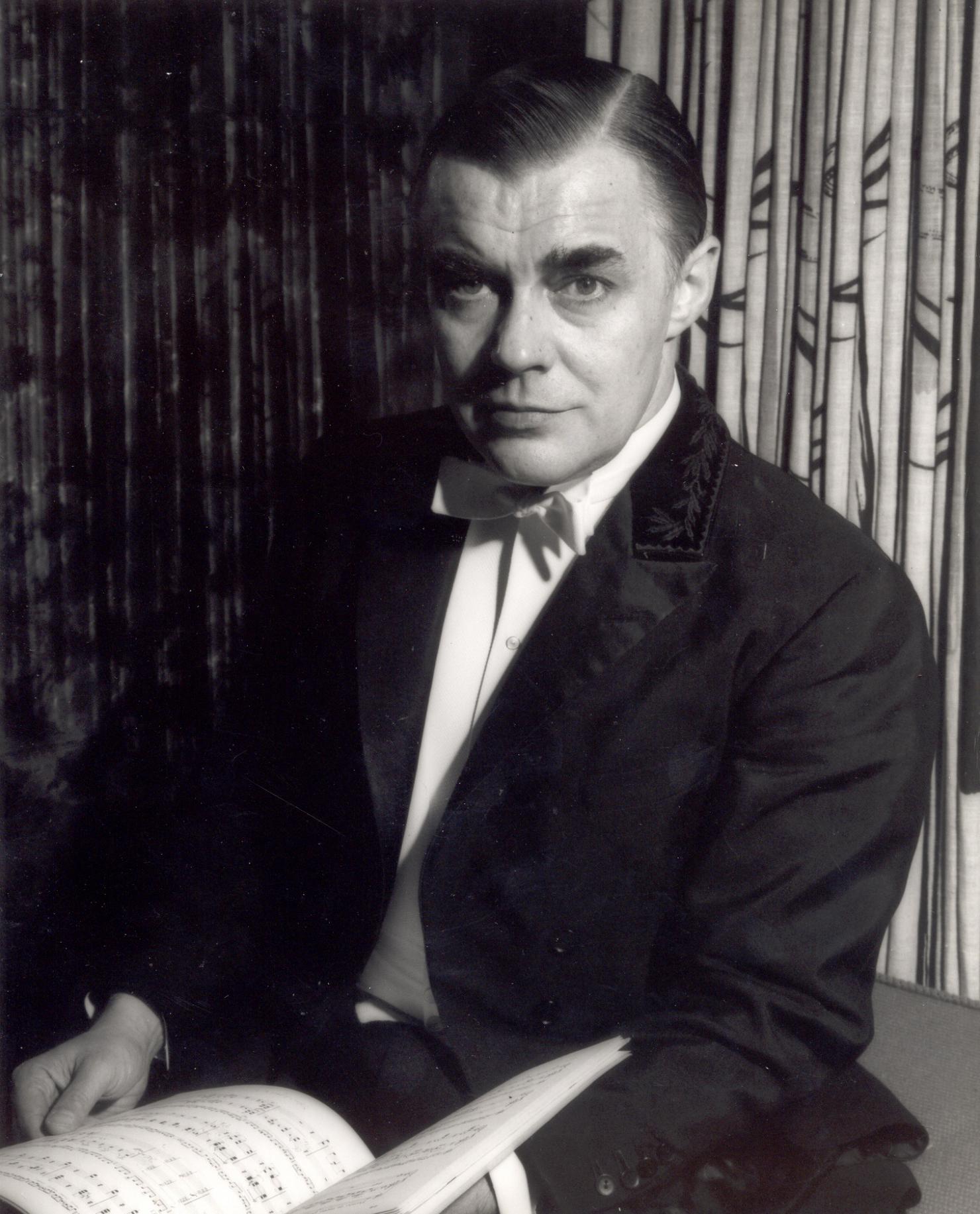

Over the years I have taken to a 1959 live recording of a performance presented on tour in Edinburgh by the Royal Swedish Opera with Sixten Ehrling leading an all Swedish cast. This is a straightforward and articulate reading of the score, the kind we expect from Ehrling, void of mannerism and at ease with its dissonance and romanticism. Perhaps because this was a touring production the Swedish company gave Anders Naslund, a relatively unknown baritone, the opportunity to sing the title role. Marie was sung by the celebrated soprano, Elizabeth Söderström who provided a potent dash of national pride in addition to her abundant sound and intelligent acting. Naslund and Söderström are exquisitely matched, he with a dark, dusty and yearning sound and she in glistening command. Naslund projects a touching vulnerability as Söderström grows in force. They are as star-crossed a tragic pair as one can imagine. Ehrling’s assured conducting completes the mental picture. Therein lies the listening pleasure of this recording.

Thinking back to that pivotal class, the here in opera hasn’t changed but the there remains an open door. Wozzeck doesn’t gather dust nor does it induce a speck of nostalgia. Even when you know it well, you don’t hum along but you do listen intently. It presents itself as a cautionary tale yet it beckons to be looked at in new ways and to have pulled from its depths meaning that is relevant to the world in which we, not only Wozzeck, live.

Whether as an artfully conceived full production, one taking place on the lip of a stage or a performance existing only in our ears and imagination, Wozzeck is a keeper.

Comments