First-rate comic experience from an immature masterpiece

ReviewWhat would you do if you wanted to revive a 200-year-old opera? A wonderful piece of music that is, like many operas of its time, absolutely irrelevant today? If you also had a solid cast and an amazing director conducting the orchestra, capable of bringing back the sound of its time with original, up to 300-year-old instruments?

Would you rather stage a classical production, giving your audience and cast the opportunity to enjoy the beauty of a time gone by? Or would you come up with an idea to make the story relevant, even modern?

Young Italian director Silvia Paoli met the challenge of this task at Donizetti festival 2018, and her solution exceeded all expectations and assumptions.

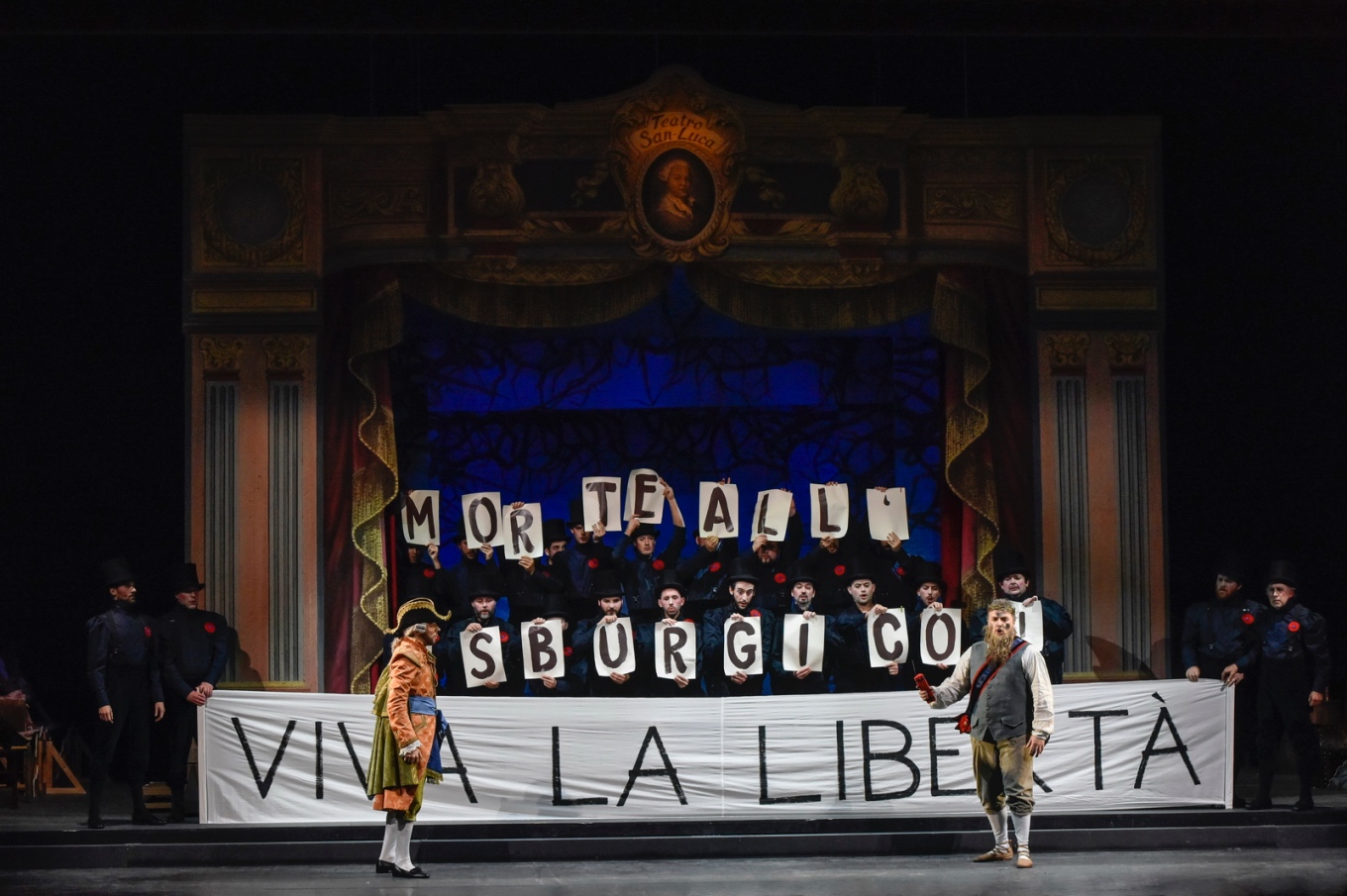

Welcome to the backstage of Teatro San Luca back in 1818, where we witness the preparations for the Donizetti’s stage debut. Every character acquires an additional layer of fictionality: Here are actors playing actors playing original characters, and a melodramatic story shaded in comedy.

Paoli uses common theatre tropes to great effect: a confused director, fighting female singers, a tenor-womanizer. The title character is played by an inexperienced and insecure young mezzo. And also, a bear onstage.

During the performance, we see their relationships unfold, disclosing the common clichés of the opera industry parallel to the development of the original plot. All of this looks cinematic, with tons of humour, bringing us back to a time when opera was perhaps more entertainment than art.

The stage rotates, and we are shown two versions of each scene. Frequently, the two realities bleed into each other, one scene colouring the other’s affect, or causing trouble - as always happens in theatre.

The main story is about the lost son of a murdered king, fighting against the weak offspring of the usurper for love and his right to the throne, successfully winning both. That’s it, literally. And this perfectly illustrates why a lot of similar operas are gathering dust on the shelves of libraries. A pity, since sometimes the musical material is real gold.

The orchestra Academia Montis Regalis under the baton of Alessandro De Marchi proved that we need to find a place for this beauty on stage. With their wooden baroque period instruments, even featuring a harpsichord, they created a special sound and atmosphere, showing once more the great aesthetic value of early music.

The prima donna of the evening in both contexts was Sonia Ganassi as Elisa. Her bold and deep voice effortlessly overcame any other voice and the orchestra. Her captor Guido, sung by Levy Sekgapane, was light and clean, the perfect example of a bel canto tenor. They both demonstrated great acting talent, shifting from dramatic characters to ridiculed singers in every scene, never neglecting the vocal challenges this opera offers, like the cadenza “La morta pud solo por fine al dolor” in Elisa’s aria, marvellously performed by Ganassi, or Guido’s final-act aria with a challengingly low tessitura.

Mezzo Anna Bonitatibus, a self-described anti-diva, was a very convincing Enrico. In the beginning, she acted and sang appropriately awkwardly, then organically developed her sound throughout the performance. Her final aria with a message of peace showcased the strength and nobility of her voice - she stole that scene. The audience barely noticed that everyone left the lead alone on stage and even started to carry out the scenery, highlighting the strength of the backstage plot.

Top laurels, however, go to two supportive actors - though it’s hard for me to call them that. Francesco Castoro with his deep and round voice was a perfect Pietro. Only he could overcome his own comic performance of fighting with the director by filling the hall with the light sadness of his first aria. His duets with Enrico were coloured with true fatherly warmth, and his sound supported Anna Bonitatibus. His was the strongest voice of the second act, and he performed luminously all the way.

And of course, the brightest character and voice were presented by incomparable bass Luca Tittoto. He sang incredibly high and very low, showing off unstrained bel canto, keeping his voice flexible and sensitive to minute changes in onstage atmosphere, from irony to fear to panic. He showed the deepest understanding of what actually happened on stage, remaining grotesque. As important and relevant as he was, his character had no particular “backstage version”, remaining nothing but a joker – Gilberto.

His part in Enrico di Borgogna had already contained signature Donizetti pieces as super fast recitatives for low voice, like those we can now enjoy in Don Pasquale, and Tittoto copped it great.

It’s hard to imagine how such a big voice could not dominate in duets with a light tenor, which made up the bulk of the second scene of the first act, but the sheer massiveness Tittoto brought to his work with Levy Sekgapane made their duets truly splendid.

And what could be more precious than ensemble parts when you have such a brilliant cast? Maestro De Marchi ended every act with a splash. The septets, dominated by Francesco Castoro, Sonia Ganassi, and Luca Tittoto, were powerful and perfectly balanced. Even accompanied by comic dances, they showed amazing colours of vocal diversity. It’s hard to believe that Donizetti composed this piece at only 19 years of age.

A minor disappointment was the chorus, which just couldn’t reach the level of the soloists. The audience definitely forgave everything after the scene where the guards, in pursuit of the villain, turned into a furious chorus bearing down on the director. The poor man never reached a mutual understanding with chorus or soloists.

Silvia Paoli, however, has definitely done it. Before the performance, Levy Sekgapane said that it was the greatest challenge to sing the piece, but also the greatest pleasure to act under Paoli’s direction. And the director herself avowed the process was “so much fun””.

In our times of experiments in opera, even more so at festivals, Silvia Paoli found a way to bring additional meaning to an old masterpiece without being predictable, thinking totally outside the box. Not many librettos are suitable for depicting backstage power struggles (could you imagine Anna Bolena or Don Pasquale productions like this?), but every word of Enrico di Borgogna fits perfectly -this opera is wholly about the assumption and retention of power. Catching this moment on stage was another achievement of the young director.

Donizetti’s Enrico di Borgogna was adapted for this production with great respect. It received a natural development most of neglected masterpieces can only dream of. So we could witness great voices, beautiful stage design and costumes, lovely atmosphere, old instruments and talented conductor, fresh and lively directing, and much more. That’s what opera is. That’s why it remains relevant today.

Comments